Narendra Modi's opponents must respect the legal system; otherwise they risk damaging the very cause they protect, says Rohit Pradhan.

Even before the final report of the Special Investigation Team on the 2002 Gujarat riots is released, the battle lines are clearly drawn. Leaked excerpts of the SIT report suggest that the Supreme Court-appointed investigative body has found no 'prosecutable evidence' against Chief Minister Narendra Modi in the high-profile Gulberg Society massacre case.

To the legion of Modi supporters, the SIT report is a clear victory; it vindicates their oft-stated stand that the Gujarat strongman has been needlessly and deliberately vilified for the 2002 riots.

His detractors, equally numerous and passionate, have adopted a two-pronged approach in response to the SIT report.

On one hand, they point out that the SIT has criticised deficiencies in the administrative response to the riots which, in their minds, is an indirect indictment of Modi. On the other hand, they have waged a relentless campaign against the SIT itself, with accusations ranging from the SIT ignoring important testimonies from the likes of the late Haren Pandya to subtle charges of professional incompetence and bias.

To set the highly charged debate on Modi in its proper context, it is important to disentangle the multiple allegations against the Gujarat chief minister into two broad categories: Sins of omission versus sins of commission.

The former is relatively simpler to understand. After all, it is indisputable that close to 1,000 Gujaratis -- both Hindus and Muslims -- died in the post-Godhra riots. Even if one admits that Gujarat has been historically prone to communal conflagrations, riots of this nature simply would not have been possible without severe administrative failure coupled with certain degree of anti-Muslim bias within the top echelons of the state government.

Rohit Pradhan is a Fellow at the Takshashila Institution, a think-tank on India's strategic affairs.

Modi has marginalised the RSS

Image: A survivor of Gujarat riots rifles through what is left of his shop in Chota Udaipur, July 7, 2002Photographs: Amit Dave/Reuters

The case against Modi is further strengthened by three factors. First, even his detractors admit that Modi is an efficient administrator and, under his watch, Gujarat has seen rapid development. How did the same administration fail so abjectly in 2002 to control the mass killings?

Second, there is no love lost between Modi and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh; in fact, Modi is one of the few leaders in the Bharatiya Janata Party with the gumption to repeatedly challenge the apparatchiks of RSS.

In Gujarat, he has gradually marginalised the RSS and its offshoots who, despite some grumbling, have been unable to challenge his authority. This suggests that, when politically expedient, Modi has easily tamed the more rabid elements of the larger RSS/ BJP family.

Admittedly, in this particular instance, Modi is damned if he does and damned if he doesn't. Nevertheless, it is a question which needs to asked: Why was Modi unable or unwilling to control the rioters in 2002, many of whom belonged to RSS-affiliated organisations?

Finally, for many of Modi's critics, his failure to directly express regret for what happened in 2002 is a severe moral failure and emblematic of his anti-Muslim bias.

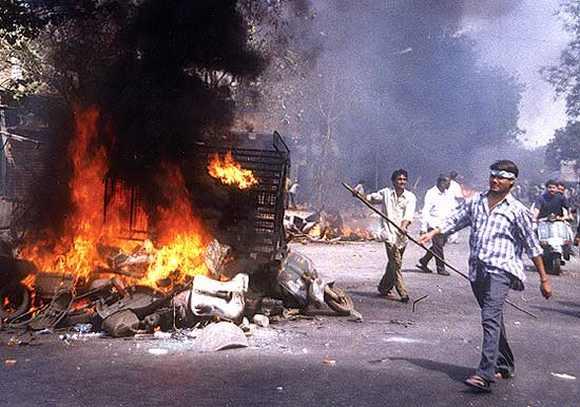

Has Modi painted himself into a corner?

Image: Rioters run amok in Ahmedabad after the Godhra train carnagePhotographs: Rediff Archives

Now, it is possible that Modi may have painted himself into a corner here. The Gujarat chief minister has portrayed the liberal crusade against him as a direct challenge to the state's 'asmita'; if he backs down now and acquiesces to the demands of the New Delhi establishment, he risks destroying his own image as an unapologetic defender of Gujarat's 'asmita'.

Nevertheless, Modi's failure to apply the healing touch in a politically meaningful way hobbles his attempt to lay the ghosts of 2002 to rest.

Modi's critics have constantly argued that the Gujarat riots were never about administrative torpor -- rather, seeking to benefit from communal polarisation, Modi gave a free hand to rioters while forcing the police to silently watch the ensuing massacre.

Modi's alleged criminal culpability in the Gujarat riots was what the SIT was specifically tasked to investigate. If the SIT report has exonerated him of criminal charges, and if this report is accepted by the appropriate courts, then he clearly has won the legal battle.

Modi can and should be confronted politically

Image: A protest against Gujarat Chief Minister Narendra Modi on April 13, 2002Photographs: Reuters

However, instead of accepting the findings of a duly constituted investigative body, many have attempted to put the SIT itself on trial. It appears that their faith in the legal process may not be as unshakable as they have repeatedly claimed -- especially if it yields results that they find unpalatable.

In fact, lambasting the legal system in India and labelling it fundamentally unfair to the poor and the marginalised seems to become an element of faith among the Left-liberal section of the Indian polity and civil society. Even the argument that SIT has 'ignored' important testimonies is fallacious.

Any investigative and judicial process rests on weighing competing narratives and evidences; mala fide intent is not proven merely because the ultimate verdict favours one particular narrative over the other.

Finally, the legal options for Modi's critics have hardly closed. They can certainly contest the SIT's findings in a judicial forum, but casting aspersions on an investigative body constituted and monitored directly by the Supreme Court is hardly appropriate.

Naturally, Modi can and should be confronted politically. It can be reasonably argued that Modi's administrative and moral failures in 2002 make him an unsuitable candidate for the highest office in the land.

Even in pure political terms, he presents a mixed bag for the BJP. While he enjoys a strong support base in Gujarat and is the clear favourite of the cadre, it remains to be seen if Modi can emerge as a leader of national stature and appeal. He also needs to build bridges both within his party as well as with powerful regional chieftains like Nitish Kumar and Jayalalithaa.

But these are political battles and should be fought accordingly.

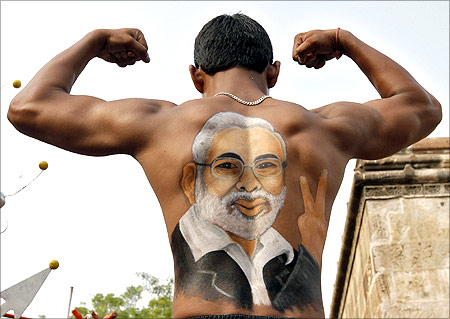

Will the Gujarat riots be Modi's stumbling block?

Image: A Narendra Modi supporterPhotographs: Amit Dave/Reuters

Modi's supporters, rightly or wrongly, believe that the issue of the Gujarat riots is raised only to thwart his inevitable march to Delhi. His detractors, on the other hand, may have couched their struggle in terms of justice but it is increasingly clear that their ultimate goal is to crush Modi's national ambitions and reduce him to the level of a regional satrap.

In a democracy, this is unobjectionab#8804 however, what should give pause to all right-thinking people is the use of the legal system fight political opponents.

Most certainly, the Gujarat riots have vividly illustrated the weaknesses of the Indian administrative and legal system. But the entire burden of that failure cannot be borne solely by Modi. After all, India's poor track record of punishing rioters and their political masters precedes Modi's rise to power.

The sanctity of the legal system and the constitutional order ultimately rests on all parties reposing faith in the system and accepting its final verdict. Waging political battles through legal means will, in the long run, damage the very cause Narandra Modi's opponents seek to protect.

article