Photographs: Zahid Samoon/Wikimedia Commons Yoginder Sikand

The badly-wounded road wound its way up the steep slopes of monster-like mountains, through endless stretches of pale green pine and slender poplars.

In parts, the forests opened out into gently undulating pastures on which little packs of sturdy horses and hairy goats and sheep feasted under the watchful eye of sturdy Gujjar herdsmen. Butter yellow wild flowers speckled the grasslands, like an intricately decorated Kashmiri carpet.

Short, dark-skinned men and women -- all Adivasis from eastern India -- (who slaved for a paltry Rs 2,500 a month, I later learnt) on the treacherous road, grinding gigantic boulders into pebbles with primitive tools.

We had left Srinagar hours ago, and had passed through Bandipora town, where shops and schools had closed early that morning. Yet another strike called to protest against yet another fake encounter in which the army allegedly killed a young lad.

We stopped for a few moments at the shrine of a Sufi saint -- known simply by the generic name 'Peer Baba', which was carefully tended to by army personnel.

Gurez and the romance of Kashmir

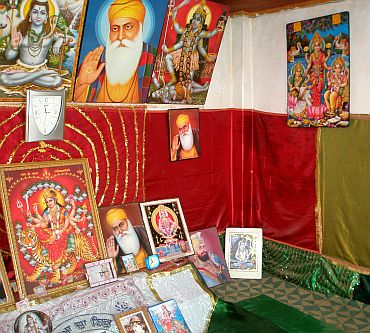

Image: Inside the shrine of Peer BabaPhotographs: Dr Harpreet Kaur

It was festooned with green flags stuck on iron poles announcing 'Peer Baba Ki Jai!' (victory to the Peer Baba!).

The man sitting next to me in the van -- a Hindu from Punjab -- who regularly travelled this route, instructed the driver to halt. He drew out a snatch of green cloth attached to a wooden handle from his bag.

It was etched with pictures of the cube-like Kaaba in Mecca and the domed mosque of the Prophet in Medina. He climbed out of the van, and, braving the howling wind, trudged up to the shrine and planted his votive offering at its entrance. I followed after him.

The Baba's Muslim-style grave was ensconced in a well-lit chamber, and adjacent to it was another room on whose walls hung pictures of Sikh gurus and Hindu deities. Marble slabs were built into the outer walls of the complex, bearing the names of deceased army officers and soldiers and offering salutations to the buried Sufi saint.

Gurez and the romance of Kashmir

Photographs: Dr Harpreet Kaur

The van courageously chugged over the 12,000-foot high Razdhan pass, and then into Gurez, an ethnically distinct region in Kashmir's northern Bandipora district, that, till recently, was virtually out-of-bounds for travelers.

From the summit of the pass a giant circle of snow-capped peaks peered out from behind a thick cloudy curtain. Glaciers dribbled down slopes till they slipped into a slim grey river thundering away thousands of feet below.

The road, even more brutally battered than on the stretch up to the pass, gradually twisted its way down into a wide, flat bowl-shaped valley, crossing swiftly flowing glacial streams on fragile wooden bridges.

We passed by Krakbal, the first village in Gurez, set in a jigsaw puzzle of little vegetable plots, bursting with beans, potatoes and corn ready to be harvested, and clumps of stunted walnut trees. The road then ran parallel to a series of mountains that marked the Line of Control that separates Indian- and Pakistani-administered Kashmir, indicated by a barbed wire fence that trailed along the perimeter along the far bank of the river beyond.

Gurez and the romance of Kashmir

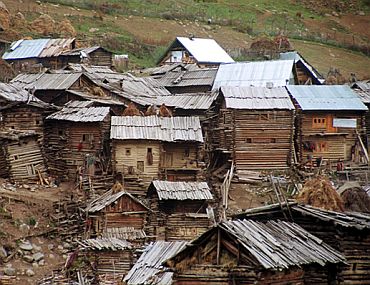

Image: Aryan settlementsPhotographs: Dr Harpreet Kaur

As evening fell we drove into Dawar, Gurez's principle settlement, consisting of under a 100 houses, mostly made of wooden planks nailed together and topped with richly ornamented sloping roofs. I settled into a two-roomed lodge, one of the few places in the village (which its inhabitants insisted was a town) for visitors to stay.

Gurez is a slender valley, surrounded by tall, impassable peaks and cut through by the Kishenganga river. It is just under a dozen miles long and two miles wide, and contains under-40 hamlets. Its inhabitants are descendants of the ancient Dards, a nomadic people of probably Afghan descent.

The Dards of Gurez are all Muslim now, but the area has an interesting pre-Islamic past. Sharada Peeth, an important centre for Kashmiri Shaivism, is located in the west of the valley, and the village of Kanzilwan, in the centre, is said to have hosted Buddhism's last grand council.

Recent excavations in the area have unearthed ancient inscriptions in Kharoshti or pre-Islamic Persian, Brahmi, Tibetan, and, according to some sources, even Hebrew. Gurez is said to have been a major halt for traders traversing the famed Silk Route that once connected China with Europe.

Gurez and the romance of Kashmir

Image: The Kishenganga riverPhotographs: Dr Harpreet Kaur

In terms of appearance, the denizens of Gurez seem no different from other Kashmiris, with whom they have been intermarrying for centuries. Yet, they still preserve their own distinct language, called Shina, which is also spoken by a distant branch of the community that lives in remote Kargil, hundreds of miles away in Ladakh.

The language is also spoken by substantial numbers of people just across the border, in Pakistan-administered Chilas, Gilgit and the Neelam Valley. Although Gurez straddles the bloodstained line that cuts across Kashmir, dividing it between two hostile neighbours, it has remained free from militancy and army repression.

Being cut off from the rest of the Kashmir Valley by a ring of towering mountains, the topography of the region makes militancy an unviable option.

Besides, the army appears to have gone out of its way to cultivate good relations with the people -- it employs them as porters (a major source of income for many locals), provides an occasional emergency helicopter service for patients needing emergency treatment in hospitals located in Srinagar and elsewhere, runs the heavily-subsidised Goodwill School at the village of Markoot and sponsors a couple of tailoring and computer centres.

Gurez and the romance of Kashmir

Photographs: Dr Harpreet Kaur

Yet, acute problems remain, and many of its people remain pathetically poor. The valley is cut off from the rest of Kashmir for almost half the year, when walls of snow, up to 15 feet thick, block the Razdhan pass, making it virtually impassable for vehicles, and forcing people to trek all the way to Bandipora on foot, a journey of at least three days.

There are only four higher secondary schools in Gurez, which means that children seeking higher education have to shift elsewhere -- to Bandipora or Srinagar -- which involves considerable expense.

Gurez still lacks a proper hospital. Locals complain of a bloated army presence, with the army having allegedly occupied large tracts land for which its owners receive just a modest sum.

Gurez and the romance of Kashmir

Image: The Habba Khatoon mountainPhotographs: Dr Harpreet Kaur

The Jammu and Kashmir Tourism Department is now working to set up facilities for tourists to visit Gurez. Simply by chance, I happened to be in Dawar the day the department had organised a jamboree of sorts -- the first of its kind -- for travel agents from Srinagar and Delhi whom it expected would be able to entice potential tourists to the valley.

There were plans to set up new trekking routes, to open up the lakes, with which Gurez abounds, to trout-fishing and water-skiing, to set up tourist lodges and even to start a helicopter service from Srinagar -- all of which, to my mind, would spell doom for this valley that had so far remained unsullied by the excesses of mass tourism.

Tents had been planted in a meadow along the river, and plates of steaming biryani were passed about as we sat round a bonfire and were entertained by a bunch of village lads wearing traditional Dard costumes (which they otherwise never did) -- flat woollen hats and embroidered waistcoats over long shirts that trailed to their knees.

I sat around for a while, enjoying the music and food. A friendly official of the department even set apart a tent just for myself. The music carried on late into the night, and it lulled me to sleep as I peered from the little net window on the roof of my tent at the enormous sea of stars swilling about in the ink-stained sky.

Gurez and the romance of Kashmir

Photographs: Zahid Samoon

In the week that I spent in Gurez, I trekked to little hamlets, stopping by to chat with people, and gazing at the sheer beauty of the mountains and the little valley that they held in their embrace.

I crossed the Kishanganga (known as the Neelam in Pakistan just across the heavily-guarded Line of Control) on a rickety wooden bridge, and walked up a narrow path, which, centuries ago, was part of the Silk Route.

I climbed past the ruins of a tax-collection pound, where traders would pay levies to a representative of the Raja of Gilgit, and the carcass of a fighter plane, which had probably crashed in one of the many wars that India and Pakistan had fought.

I trekked all the way to Chorwan, the last Indian village, and would probably have wanted to go even further had a posse of ferocious armed guards not stopped me. I circled the cone-shaped Habba Khatoon hill just outside Dawar, which is where a Kashmiri king is said to have met the dazzling damsel after whom the hill is named -- the plot of a classical Kashmiri romance.

I spent an afternoon at a mosque-school in Bakhtoor, engaging in discussions about matters esoteric with the local maulvi (Muslim priest). I hitched a ride in a van and headed to Tilail, where peaks and army pickets in Pakistan were clearly visible, wondering about how an arbitrarily-drawn line had so tragically divided a people from their own kin, who now lived in what was defined as 'enemy territory'.

It was with a heavy heart that I finally left that delightful little valley, bumping along the boulder-strewn road back to the scarred valley of Kashmir beyond the encircling mountains.

article