| « Back to article | Print this article |

'We won't become a great country'

Video: Rajesh Karkera

'I don't think any politician now can kill growth for the next couple of decades,' Gurcharan Das tells Rediff.com's Vaihayasi Pande Daniel.

'We will continue to have these very slow, incremental, reforms. Then we will hit a wall. That's the wall of bad governance.'

'Unless we fix our governance, we won't become a great country.'

You may call Gurcharan Das: Former CEO, Proctor and Gamble.

You can call him a columnist, whose writing has appeared in Dainik Bhaskar, Prabhat Khabar, Eenadu, Sakal, Mathrubhumi, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, Time.

You may call him a writer, with several plays, essays, a novel and books to his name -- The Difficulty of Being Good, India Unbound, The Elephant Paradigm, A Fine Family.

You can call him a child of Partition, born in 1943 in Lyallpur (now Faisalabad, Pakistan), hailing from a family of government servants, who grew up in several towns in north India, where his father's job postings as an engineer took him -- Bhakra Nangal, Simla, Delhi.

You may call him an alumni of Harvard, where he studied philosophy under the eminent American philosopher John Rawls and later business management.

It is best to simply call him a hopeful Indian, like you and me, seeking a more radiant India.

India has been the main, and most colourful, character in many of Das' books. And certainly his latest -- India Grows at Night -- is dedicated to energising Indians to find that elusive solution that will allow India to shine, in spite of appalling governance, clueless, crooked leaders and inadequate infrastructure, that is strangling her once galloping growth rate.

Das discusses the future of India with Rediff.com's Vaihayasi Pande Daniel:

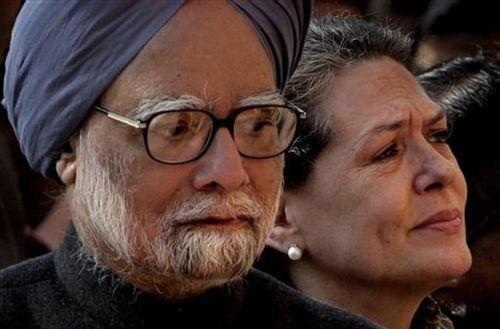

In your view, why has Prime Minister Manmohan Singh become so ineffective?

I think it is a combination of his personality. He is a gentle, timid man. A nation needs more determined people.

What his rule, or period of prime minister-ship, teaches us is that determinism is more important in a leader than intelligence. He is a PhD in economics. A very, very, intelligent man.

That's the mistake we make. We get tempted into believing that... Somebody comes to your company (and) you are supposed to hire: "Oh my god, a great CV, went to Harvard... and did this." Point is: You are judging the person's intelligence there.

Determination. Will. It is will that makes the world go around.

Are you despondent about what is happening in India, specifically its corruption, this crony corruption?

I would say so.

My personal journey that I recount (in India Grows at Night) goes something like this:

In India Unbound, I spoke about the fact that when I was young -- like everybody -- I was a socialist, in my 20s, early 30s even. Then I saw that the socialist model of Nehru was taking us to a dead end.

Then also (as) I recounted in India Unbound some of the personal humiliation I suffered as a CEO of a company.

So when the reforms came I became a libertarian. I began to believe in a laissez faire State.

I began to believe that the less government we had, the better. I began to believe that India could grow at night when the government slept.

The big change now is that from that libertarian perspective I have become a believer in the classical liberal State. The classical liberal State is the State that inspired our founding fathers, as well as America's founding fathers.

That State has three pillars. It has an executive, that can take strong determined action. That action is bounded by the rule of law and it is accountable to the people.

Now in my own case, I had begun to believe earlier, in my libertarian phase, that the State is a second order phenomenon. Now I believe it is a first order phenomenon.

I also believe that some of the success India has achieved is actually because of good regulators.

Even the reforms were done by good regulators. But those good regulators are an exception. We need more of such regulators. We have had very good Election Commissioners, Reserve Bank (governors), SEBI (chairmen). These are some of the good regulators.

Even the first TRAI (Telecom Regulatory Authority of India) made the revolution in cell phones possible. And you have to give credit to (then prime minister Atal Bihari) Vajpayee, who stood his ground against the Department of Telecom, who wanted to crush the new competition from the private sector.

And so it is a change in perspective, I believe, for myself (too). So I believe today, that more important than even economic reforms are governance reforms.

And I don't think there is a silver bullet on how you can achieve it. If we are lucky we can get a strong leader, an Indira Gandhi-type of leader, but (someone) who is a reformer. She was a destroyer of institutions. A builder of institutions -- that is what we need.

So what's the answer? Where do we go from here? If we are lucky we will get a good leader, but you can never guarantee that in a democracy. So I put a lot of hope in the middle class.

There is a chapter (in my book devoted to) middle class dignity. I feel today (the middle class) is about a third of India and by 2020, in ten years, it will be half.

When it becomes half, then the politics of the country will also change. That is why I recommend a political party that caters to that class and which will be single-mindedly be focused on reforms -- economic reforms, reforms of institutions and be secular.

So that's what you perceive is the future. Let's go back to the present: Would you agree that all the present set of politicians -- across party lines -- totally lack a vision for India?

Do we have anybody, at this time, who can lead us?

No, I find it very hard to vote for anybody.

I mean I don't know who I would vote for.

All the parties treat me as a victim.

The Congress party says that you are a victim of globalisation, liberalisation, therefore we will give you free power, Rs 4 rice, diesel subsidy and yeh and woh.

The BJP says you are a victim of a thousand years of Muslim invasions.

The Dalit party says you are a victim of upper caste oppression.

And the OBCs (Other Backward Classes) say the same thing.

So no party is treating me (addressing me) -- this one-third of India which has risen; and they are aspirers and they want to see that vision -- and nobody is giving them that vision.

So you are basically saying that you don't see anybody?

No, I don't.

That's why I am suggesting: Let's revive the Swatantra Party (a liberal political party started as a counter to Jawaharlal Nehru's socialist policies in August 1959 by Chakravarti Rajagopalachari, the last governor general of India, and freedom fighter N G Ranga.

Please click Next to read why politicians may not be able to stop India's growth...

You can buy India Grows at Night at the Rediff Bookstore.

Modern India is in some ways Gurgaon writ large

Has India lost the opportunity to become great because of what we are paralysed with at the moment?

Are we capable of capitalising on our demographic dividend? How should we do it?

I think, personally, no one can really stop the growth for the next couple of decades. So in that sense I don't think any politician now can kill growth.

We will continue to have these very slow, incremental, reforms. If they would reform a little faster, we would obviously grow faster.

But I think we will become a middle income country, which means from a $1,500 to $1,600 per year per capita, we will reach $5,000 to $6,000 per capita per year.

Then we will hit a wall. That's the wall of bad governance.

Unless we fix our governance, we won't become a great country. So we might as well fix it now.

An excerpt from Gurcharan Das's India Grows at Night on how Gurgaon was born and how it grew and how it may not grow further:

Kushal Pal Singh, 'KP' to his friends, is a hugely successful builder who is fond of narrating the tale of two adjoining towns on the outskirts of Delhi -- Faridabad and Gurgaon.

In 1979, Faridabad had an active municipal government, fertile agriculture and a direct railway line to the national capital. It also had a host of industries -- including one owned by KP -- and a state government that was determined to make it a showcase for the future.

Gurgaon, on the other hand, was a sleepy village with rocky soil and pitiable agriculture. It had no local government, no railway link, no industries, and its farmers were impoverished.

Compared to pampered Faridabad, it was wilderness.

In 1979, the state of Haryana divided the old political district adjoining Delhi. It gave the better half to Faridabad; the worse half became Gurgaon.

When an official of the Haryana government in the early 1980s made a presentation to investors about making Gurgaon a city of the future, he was laughed out of the room.

Anyone in Delhi, including my brother, who wanted to invest in industry or in real estate, was advised by their friends to go to Faridabad.

Thirty years later, Gurgaon has become the symbol of a rising India. Called 'Millennium City', it has dozens of shiny skyscrapers, twenty-six shopping malls, seven golf courses, countless luxury shops belonging to Chanel, Louis Vuitton and others, and automobile showrooms of Mercedes-Benz, BMW and Audi.

It has 30 million square feet of commercial space and is home to the world's largest corporations -- Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, GE, Motorola, Ericsson and Nestle among them. Its racing economy is reflected in its fabled apartment complexes with swimming pools, spas and saunas, which vie with the best gated communities anywhere.

Faridabad remains a sad, scraggly, would-be town, groaning under a corrupt, self-important municipality; it is still struggling to catch up with India's first wave of modernisation after 1991.

Gurgaon's disadvantage has turned into an advantage. It had no local government, nor planning authority. It was more or less ignored by the state government until it became successful and then only as a source of graft. This meant less red tape and fewer bureaucrats who could block development in Gurgaon.

But Gurgaon had destiny. Meaning 'village of the guru', it belonged according to legend to Guru Dronacharya, the martial arts guru in the Mahabharata. In the epic, the kingdom of the Bharatas is also divided: The better half goes to the Kauravas and the worse half to their cousins, the Pandavas.

But the Pandavas are diligent, hard-working and determined; they clear the land, make shrewd alliances, and build a magical city, Indraprastha.

Archaeologists believe this city may be buried under South Delhi or close to it. Could Gurgaon be the twenty-first-century equivalent of the magical Indraprastha?

Gurgaon has risen with little help from the state. It only got its municipal corporation in 2008. Its ineffectual but arrogant planning authority, the Haryana Urban Development Authority, was continuously overshadowed by the speed and energy of private developers like K P Singh, whose company Delhi Land and Finance Ltd is one of the secrets behind the miracle.

Instead of planning for the future, HUDA was always planning for the past; it had collected more than Rs 10,000 crore in infrastructure fees -- an impressive sum -- but few could say that the money had benefited the city or its residents.

The downside of rising without the State is that Gurgaon does not have a functioning sewage or drainage system; no reliable electricity or water supply; no public sidewalks; no decent roads; and no organised public transport. Garbage is regularly thrown into empty plots of land or by the side of the road.

So, here is the puzzle: How did spanking new Gurgaon become an international engine of economic growth with minimal public services?

Gurgaon manages to flourish without public infrastructure because of its self-reliant, resilient citizens. They don't sit around and wait.

They dig bore wells to get water when government pipes run dry.

They put in diesel generators when power from the state electricity board fails.

They use cell phones from private providers rather than landlines of the state company, Bharat Sanchar Nigam Ltd.

They use couriers rather than the post office.

Many companies have even installed their own sewage treatment plants.

Apartment complexes and companies employ tens of thousands of security guards rather than depend on the police.

When teachers and doctors do not show up at government primary schools and health centres, people open up cheap private schools and clinics, even in the slums.

Private schools of all kinds are flourishing on every street -- even the poor can find one to fit their pocket, where fees are as low as Rs 150 per month.

To rise without the State, as Gurgaon has done, is a brave thing, but it is not sustainable. Gurgaon would be better off with a functioning drainage system, reliable water and electricity supplies, public sidewalks and parks and a decent public transport system.

Indeed, it should also 'grow during the day'. Moreover, the truth is that the State has not been entirely absent in Gurgaon. It has just not been effective. It has managed to provide a degree of security, law and order, property rights, town planning and even some infrastructure.

Gurgaon would be a happier place if the State were to begin functioning effectively and honestly, and helped to improve infrastructure.'

Modern India is in some ways Gurgaon writ large. The nation's ascent also baffles Indians, and it was reflected in my inadequate, hesitating responses to the Egyptians.

Middle class Indians, who now constitute almost a third of the country, believe that their nation is doing well because the pre-1991 over-regulating State has gradually liberalised. They point to the information technology industry as the quintessential example of India's rise after 1991 without interference from the State.

To them, the entrepreneur is at the centre of this success story as India now has dozens of highly competitive private companies that have become globally competitive.

Meanwhile, the State has not kept pace. It has not provided enough electric power, roads, ports, water, schools and hospitals -- the entire infrastructure needed for a rising nation. Nor has it allowed the private sector to build it in adequate quantity.

The middle class envies China's extraordinary infrastructure, which has enabled it to rise.

Extracted from India Grows at Night by Gurcharan Das, Penguin India, with the publisher's kind permission.

Please click Next to read why the Gandhis may not be the right family to rule India...

You can buy India Grows at Night at the Rediff Bookstore.

'I don't think Rahul has shown the qualities of being able to lead the nation'

In India Grows at Night, you mention that when you were in Egypt last year you were asked how India has always kept the generals out of power.

Further, you refer often to Jawaharlal Nehru and the damage done by his economic policies and to Indira Gandhi and the destruction caused by her era of leadership.

We blame Nehru and Indira for so many of India's problems pre-1991. But would you not credit both Nehru and Indira for the fact that the generals have never controlled India?

I give a lot of credit to (Jawaharlal) Nehru. He created and set in place the institutions (of the State -- structures that maintain social order) -- and actually that whole first generation (did).

You remember (in my book) that comment by (Sardar Vallabhbhai) Patel against the general (shortly after Independence, British General Roy Bucher protested to Nehru and Patel about the government's decision to take military action in Hyderabad. Bucher said he would resign if India insisted on proceeding with it. Patel told Bucher that he could resign, but the action would start the next day. Earlier, another general told Nehru that the public should not be invited to a ceremony to transfer power from Britain to India. Nehru told him India was now ruled by the people and cancelled the order and in that manner right from the start established a pattern of civilian control for India).

They (Nehru and his government) set the tone for the country and the country kind of stayed on it.

But for me Indira Gandhi really was very much more problematic. Her legacy is more bad, than good.

But in this particular context, don't you think she did have a legacy? She was strong so there was no room for the generals. We won the Bangladesh war. She took a decision to annex Sikkim.

You could look at it that way (he says reluctantly).

The more interesting question is that you have had very weak prime ministers also. And the generals have never been tempted. Very weak governments.

We have had minority governments in India -- (P V ) Narasimha Rao's government, the Janata Party rule, before that, after the Emergency. And then the Inder Gujral (government), the (H D Deve) Gowda (government), so many.

This has been one of the weakest governments we have had.

So it's (actually) the (solid) institutional framework (that kept the generals out) for which you (can) credit Nehru more.

Do you think you are being harsh in your summing up of Jawaharlal Nehru through the book.

In the sense that Nehru was less socialist than many of the people of his time. He erred in his economic policies, but he established so many of the institutions that made India what it is?

I agree with that.

But we have to admit that (as far his economic policies go) that was a wrong path.

It was not the path that the country needed and given the strong institutions that he was creating, if he had given more freedom, also to the private sector, then he would have done even better and (India) would have had higher growth.

We deliberately suppressed growth. A private company could not set up a steel plant. The Birlas wanted (to set up a) steel plant because the Tatas had one (the Tatas' plant was set up pre-Independence) and they were not allowed to set it up, because it was a monopoly.

The point is: The License Raj prevented growth.

The Gandhi family believes it has led/guided India since Independence. Or have they done more harm than good?

I believe we owe a great deal to Jawaharlal for his contribution in building the institutions of our democracy. He played an invaluable role, supported by that entire first generation of leaders.

I think his flaw was socialism. You cannot blame him too much because the whole world was socialist back then. He was a creature of his times, but frankly even socialism could have been better implemented. It did not have to degenerate into License Permit Inspector Raj.

You can have a mixed economy with a (strong) public sector, but you have to make that public sector accountable and autonomous.

You did not have to stifle the private sector at the same time. There was a problem -- I mean that the License Permit Raj had come up during his time. That expression was first used by (C) Rajagopalachari in 1959. So whether it was the spirit of the time or not, it was the wrong model.

If the private entrepreneurs had had a little more freedom -- like if the Birlas had been allowed a steel plant. They had all these industries reserved only for the public sector.

You couldn't have a private airline competing with Indian Airlines. You couldn't have a private steel plant come up and compete with a government steel plant. That was the great, great, flaw of Nehru.

People condemn Mrs Gandhi for the Emergency. But I condemn her for two other reasons. One is that it was the worst period in India's economic history. Nationalisation of banks. Her Garibi Hatao programme... Indira Gandhi played a very negative role in making our institutions -- which are crumbling today -- (begin) crumbling from that time

She believed in a committed police, a committed judiciary and a committed bureaucracy, but committed to her.

Rajiv Gandhi was a real breath of fresh air. In fact some of the reforms that he did in 1985 lifted the economy very quickly. Unfortunately, he did not have a talent for running things. And he just did not know how to control the Congress party.

He just did not have the leadership skills. But he had the vision. He had the mandate. A stronger man would have done a lot more.

I think Rahul is an intelligent person. I don't think Rahul has shown the qualities of (being able to lead the nation) which are required. He is a great guy to be a friend! I have a lot of sympathy for him.

Sonia Gandhi unfortunately modeled herself in her economic policies to her mother-in-law, Indira Gandhi. She has followed a populist policy that can damage India.

In chapter seven of the book I am really very critical of political dynasties. I think the biggest mistake Nehru made in his life, one of the biggest mistakes, was to let Indira Gandhi become president of the Congress party in 1958. I think that's where the rot started.

Please click Next to find out what Gurcharan Das learnt in Egypt about India's democracy...

You can buy India Grows at Night at the Rediff Bookstore.

Anna Hazare, Jantar Mantar and Tahrir Square

An excerpt from Gurcharan Das's new book, India Grows at Night on how he learned something vital about India in Egypt:

In Tahrir Square this book was born on a visit to Egypt. On 8 April 2011, the day before Anna Hazare broke his fast, I was in Cairo to present the 'Indian model' for Egypt's future at a conference of liberals from their democracy movement.

I had been reluctant to leave Delhi when history was in the making at home, but I agreed in the end. It turned out that instead of teaching the Egyptians something about democracy, I ended up learning something about India.

Cairo's Tahrir Square reminded me of Jantar Mantar in Delhi where I had seen the seventy-four-year-old Anna Hazare in a white villager's cap a few days earlier. Both were non-violent protests reminiscent of Mahatma Gandhi.

Anna's hunger strike in particular was evocative of Gandhi's tactics. And like Gandhi, he had put a powerful government on the defensive. His fast was in support of the Lokpal, an anti-corruption agency to investigate complaints against politicians and officials. Clearly, Anna was no Gandhi -- not even a pale copy -- and while his movement had succeeded in creating awareness about corruption, I felt ambivalent because street revolutions are dangerous in a settled democracy.

A year earlier, however, no one in India could have imagined that Cabinet ministers, powerful politicians, senior officials and CEOs would be in jail awaiting trial for corruption.

The credit for this belonged in no small part to Anna's movement, supported by determined justices of the Supreme Court, and a newly assertive Indian middle class.

A series of scandals had enraged the middle class, the media and the Opposition parties. These included graft-ridden purchases for the 2010 Commonwealth Games in Delhi, for which rolls of toilet paper worth Rs 40 had been purchased for Rs 400; mobile-phone spectrum had been 'given away' to favoured companies at prices so low that it had lost the government between Rs 40,000 crore and Rs 160,000 crore in licence fees; and pricey apartments in Mumbai had been 'grabbed' by politicians, officials and generals.

These were some of the headline-grabbing examples of India's crisis of governance.

But the Egyptians did not want to hear about these things. They were too busy with their own problems and they asked me three difficult questions. First, how did India keep its generals out of politics?

Second, how did it manage to create a sense of security for its minorities? (They explained that 11 percent of Egypt was Coptic Christian while 13.5 per cent of India was Muslim; but why did Muslims in India feel secure while Christians in Egypt did not?)

And third, what could Egypt learn from India's success in winning outsourcing business from the world's largest companies and become a rapidly growing economy?

I did not have satisfactory answers to any of their questions, but they did force me to think about India in a fresh and new way.

When the conference got over in the evening, some of us wandered over to Tahrir Square nearby for a bit of sightseeing. We had heard that a massive demonstration had broken out that day against Hosni Mubarak, and we thought we might catch a moment in history.

But through a twist of fate, I found myself on the podium, quite unexpectedly offering good wishes to 27,000 protesters from 'the people of Al Hind, the land of Mahatma Gandhi'. I was given three minutes to speak and in that brief time I spoke off the cuff about what I thought was the most important lesson from India's experience with democracy.

I said to the crowd that democracy entails many things -- elections, liberty, equality, accountability. But the hardest thing to achieve in practice is the 'rule of law' and the idea that no one is above it. To attain that, strong institutions of governance were needed.

'You would not be protesting today,' I added, 'if Egypt possessed the rule of law and if Hosni Mubarak did not think he was above it.'

Then I told the Egyptians that while India was a proud democracy, its governance institutions had weakened, corruption had grown and indeed we had our own Tahrir Square movement.

I woke up that night at three to the sound of gunfire. At first I thought they were bursting crackers in the square. Soon there was a knock on the door. It was my host, who whispered that the army had moved into Tahrir Square and I should be prepared to flee as my 'three minutes of fame' had been posted on YouTube.

Filled with fear, I changed quickly, picked up my laptop and passport, and sat and waited. I must have fallen asleep because the next thing I remember is that it was seven o'clock. I was still alive. I saw a cloud of smoke above Tahrir Square; I switched on the television to learn that the army had indeed come, but it had left as quickly, leaving two persons dead. It had been searching for soldier-protesters.

I returned home the following day, much relieved. I picked up the morning newspapers in Delhi to find a number of editorials and op-eds comparing, somewhat simplistically, Jantar Mantar to Tahrir Square. They were wrong to do so.

The defiant faces in Tahrir Square returned to me hauntingly: In their eyes was rebellion, but there was also fear. They had been right to be afraid as it turned out. I had never had to fear the army in India, nor had to think about the first question of the Egyptians.

India was not that kind of a State. What those eyes in Tahrir Square did not comprehend was that self-government is a slow, painful and demanding process, and ultimately depends on certain 'habits of the heart'.

Indians still needed to learn those habits. But the Egyptians did provide me a new perspective on India.

What Anna Hazare's campaign against corruption had in common with the Arab Spring was an awakening in both countries of the new middle classes, especially the young, who had begun to believe that they mattered politically and were now demanding accountability from the State.

Anna had also seeded the idea that accountability could only begin when each watchful citizen became aware of his personal dharma.

'I Am Anna', written on the Gandhi caps worn by the members of the Anna movements, symbolised this moral revolution.

Those who vilified his campaign for attempting to usurp Parliament's authority forgo in their arrogance that in the eyes of the ordinary citizen he was a reflection of public dharma -- the same one whose symbol was placed in the middle of the Indian flag in the form of the Ashok Chakra.

This dharma had been wounded by corruption.

Extracted from India Grows at Night by Gurcharan Das, Penguin India, with the publisher's kind permission.

Please click Next to find out about the five things that will help India become great...

You can buy India Grows at Night at the Rediff Bookstore.

'Good people don't have the motivation to do well'

Do you think the greatest adversary of India's economy is its politics, which is always going to be harnessed by vote banks?

I think more than politics the adversary today is weak institutions. In other words, in a democracy you cannot guarantee what kind of politics you are going to have, but if your institutions are strong (it does not matter).

If the judicial institutions work well, you don't have to wait 12 years to get justice. You should get it in three. That's what matters to a person.

You shouldn't wait 12 years to build a road. You should be able to build it in three.

If you want to get a birth certificate, you shouldn't have to bribe somebody to get a birth certificate. That's the soft underbelly of India.

But if the votebank does not want that particular road so it doesn't get done?

The voter would love to get the road, would love to get drinking water, would love to have the teachers show up in government primary schools.

But he doesn't necessarily want, say a sea link... It is politics that prevents us...

You are right that's part of being a democracy.

Democracy is a weak form of governance because a fishermen's lobby can stop a road. Everybody goes to court. That is partly a systemic problem.

If you had quick functioning courts, you would get quicker justice and that resolution of that fishermen's case would also be faster.

What would be the five ways that you would suggest to get India going again? Apart from this mending of institutions and systems.

It is all five around them.

You know the answers are all there. Meaning there are enough commissions -- administrative reforms commission, police reforms commission, judicial reforms commission, even the Constitutional reforms commission. All these are there.

They haven't been implemented. All we need to do is pull those things out -- (snaps his fingers) -- and implement them. (The recommendations) are very sound and there is not just one commission, many commissions, you can easily choose from them.

But the key factor is, for example, the bureaucracy.

If you don't differentiate between good officers and bad officers. If everybody gets promoted on the basis of seniority. If 80 to 90 percent of your civil service is rated as excellent. Then you are not differentiating the good from the bad.

So the good people don't have the motivation to do well. And the bad people don't have the motivation to do well either because they won't be punished (for doing badly).

In another system the people who don't perform will be punished -- (they) will be gone or would at least not get promoted. But here everybody gets promoted. Everybody gets the same salary.

So you don't differentiate between people who work till midnight, work very hard -- and there are those -- versus those who don't do their job.

India Abroad, the oldest Indian-American newspaper owned by Rediff.com, honoured the US Attorney for the Southern District of New York, Preet Bharara.

In today's India, especially in today's India, an honest person like Preet Bharara don't even have a place. He cannot exist.

Honest people cannot exist.

I won't say: Cannot.

You have judges who brought the 2G scam people to their knees.

You have the CAG who has brought the government to its knees.

So they are there.

They are fewer such people. And they really have to work against the system. The system doesn't promote such people.

I am not sure how many Preet Bhararas there are in the American system either, but I would think there would be many more than they would be in India.

Please click Next to find out why we should believe that eventually India will shine...

You can buy India Grows at Night at the Rediff Bookstore.

'The Indian State was never strong'

There is a constant disconnect between the elite and the poor since Independence in India.

When we start opening up the economy, the poor are immediately worried about what is going to happen to their agricultural products, the subsidies they depend on and all that.

We, the elite, are always assuring them that when we have market reforms, when the free market is in place, all their problems will go.

When you look at it from their perspective, the elite of India has always let these people down, right from beginning. Is that not so?

I don't agree with this class analysis. This kind of class analysis is very Marxist.

But you are absolutely right though.

Where I agree with you is that it is very hard for a person to see that if I invest in a road, which will take three to five years to build, then that road will connect two towns and create opportunities for trade and for investment and therefore prosperity will begin.

Adam Smith said when everybody follows their self interest, what happens is, the invisible hand (the invisible hand of the market is a metaphor conceived by Adam Smith to describe the self-regulating behaviour of the marketplace) -- there are lots of companies producing things, then the competition between the companies ensures that the products are good quality and that they are the best and at the lowest price.

That invisible hand is very hard to see because it is invisible.

That's why a reformer will lose out in an election to a person who says: 'I will give you Rs 4 for a kilo of rice. I will give you free power.'

The reformer will say: 'Damn it, who will pay for that free power in the end?' This is why a reformer will always be at a disadvantage. This is the sad fact. He will be the one the farmer will not believe.

That is why reforms are easier to do in autocratic societies. In China they don't have to worry for votes and they just go ahead. They put roads. They don't even care if they displace people or anything like that.

Don't make it a class thing. Because every human being is self interested. Nobody does anything altruistically. The elite is never going to do anything altruistically anywhere.

But you are absolutely right that it is very difficult to see the value of that rational discourse of reform.

I tell you, I am going to build a school. School will come. School teachers will come. Children will go to school. It will take parents 10 to 12 years before they see the benefit.

So they would rather have Rs 4 kilo rice, today. Free power, today. So populists have an advantage.

Would you say that this sense of dharma, the impetus to do the right thing, that you refer to in your book, as being linked to the nature of Indian people, right through history, is the reason why India has not succumbed to a Russia or China kind of situation?

Partly you are right.

But partly what accounts for this fact is that the Indian State was always weak.

I would recommend you read in my book that chapter -- it is my favourite chapter, a historical chapter -- it is called A People But No State.

An Indian State was never that strong, which allowed itself to penetrate society, so that it could dispossess people of their rights. The king in India was always weak.

Society was strong.

Oppression came from the Brahmins. The answer to the oppression was the Buddha (smiles).

It never came from the State. We did not have the strong oppressive State in India. It is one of the benefits of the caste system. It is one of the benefits of strong cultural institutions -- the Brahmins and so on.

One is always looking for rational facts to support one's deep emotional belief in India. That seems to be the underlying theme of your latest book too -- a belief that India won't lose its way, in spite of the ups-downs it goes through from time to time and decade to decade?

If you read the conclusion to my book there is a section called: The code word. The code word is something that unlocks the secrets of a country.

America does all good and bad things in the name of liberty.

France does all the good and bad things in the name of egalite (equality)).

In India it is Dharma.

Dharma is -- because my columns appear in Dainik Bhaskar and other Indian newspapers -- I sometimes read those newspapers and I realise that constant rhetoric during this corruption movement was that: Dharma has been wounded.

This country -- despite the efforts of the BJP and Hindutvawallahs, who are trying to semitise Hinduism -- is (pluralistic by nature). Actually when you have 330 million gods, no god can afford to be jealous.

We have a plural temper. So that's a liberal temper to begin with. So it is these things.

We spoke about how the elite of the country always let down the poor. Mahatma Gandhi was an Indian who was extremely non-elitist.

Would you not agree that many of Gandhiji's views are still relevant even a hundred years later?

I think he is important to the moral core. (He represents) the moral core (of India).

I think his economic policies were disastrous. His whole decision of swadeshi was fine for winning independence and for capturing the imagination of people. It was not the right economic policy.

Similarly, his political ideas were based on a self-sufficient republic. The village being a self-sufficient republic. I think that was hare brained. He had some very Utopian ideas which I am glad we never got into.

There were some Gandhians who did some damage after Independence. One of the more damaging policies enacted was the reservation for small scale industries. 800 industries were reserved for the small scale sector.

Absolute disaster. That is one of the reasons why we need an industrial revolution...

Please click Next to find out what each of us needs to do to make India great...

You can buy India Grows at Night at the Rediff Bookstore.

'What Gujarat has achieved, that's what India needs today'

What then are India's greatest advantages?

There are several advantages.

One, is the fact that we are already a democracy. In other words we may not be a very, well-governed democracy but we are a democracy. So the voice of a person is heard.

And that was what really came to me in a very real way in Egypt (when) they asked me about Indian democracy.

The second advantage is that there is a moral core in the country. A good democracy must have a moral core.

The thing is we need to now energise that core.

It is like a battery that has gotten charged down. We need to charge up that battery. We need to translate the ideal of the Constitution into the language of universal dharma.

That is a job of politics. Sometimes politicians do that. Periodically American politicians, when they speak, will talk about the basic values of the constitution etc. I think we need to talk more about those basic values.

But to make sense to the people that rhetoric will be the rhetoric of dharma, the way Gandhi did, when he was fighting untouchability.

The third advantage is that already from 1992 onwards, since the 73rd Amendment to the Constitution was enacted, we have had devolution of authority going very slowly but that process has been going on (The 73rd Amendment Act contains provision for devolution of powers and responsibilities to the panchayats, both for the preparation of economic development plans and social justice, as well as for the implementation in relation to 29 subjects listed in the 11th schedule of the Constitution).

So the habits of the heart are built when you conduct in your neighbourhood that local democracy. Whether it is the municipality or whether it is (the ward), it is through local democracy that you learn those values that become habits of the heart.

So these are some advantages that we have going for us. Also going for us, I think, is the fact that we have become a high growth economy.

In a high growth economy there is a rise. People rise out of poverty, rise into the middle class. There are levels of these risings going on. So some of the basic problems of survival are being (solved).

People are a little more at ease economically. This gives them more time and attention to (absorb and be aware of) politics.

What is your message to the average citizen who believes in India and has the potential to participate, but does not know where to begin?

What can he do for the country, especially when governance is weak but India is still growing?

In my chapter called -- What is to be done? -- I am emphasising the need for every person to engage in the neighbourhood. I give this example, in the book also, about working in a ward -- there was someone talking to me, Shashi Kumar who lives in Gurgaon -- and I was suggesting to him to work in a ward.

Even to devote an hour or two a week is a good start. I think democracy begins in one's neighbourhood and that's best way to become effective.

So instead of shying away -- here in our neighbourhood, where I live in Delhi, in Jor Bagh, we have a very active local group of citizens and they do many things. There is a sanitation committee, a committee for electricity and for security.

Do you think in some ways secularism hinders India? Do we need to give ear to the Hindutva folks and their views that our plurality and our plurality-supporting policies endanger the country via terrorism?

Do you feel terrorism in some form can be damaging to India?

The Hindutva people are complaining about a lot about the vote bank politics of the Congress. And that, of course, is a problem.

The answer is no. I think secularism does not stop us from progress, just as I don't think caste stops us from progressing either.

We are a very plural country. Despite Gujarat, the Muslims of India probably feel more secure in India than Muslims feel in any other country where they are in the minority.

I think one of the reasons is because of democracy. And the other is the basic plural temper of the people.

Hindutva is really a fringe activity. The whole Hindutva strategy is not sustainable, long term, because it goes against the basic temper of the country.

The future of India is going to be invested in the cities of India. Caste is a problem really in the rural belt. In the modern economy there is such a desperate need for talent. So if there is a talented Dalit person or a talented Muslim he will get a job.

People are desperate to get people who are performers. In many areas we are digging at the (bottom of the) barrel. We don't have the people.

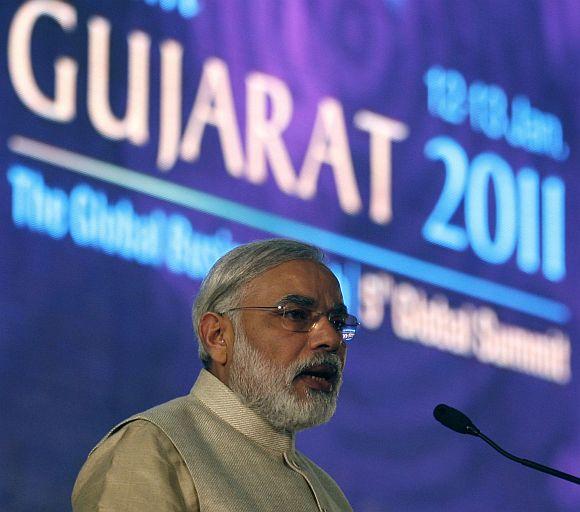

What about the conflicting nature of Narendra Modi's Gujarat? Are we to believe that an authoritarian but apparently efficient figure like Modi can still lead a state and maybe a country to progress?

Should we support people who are efficient even if they might have suspicious track records?

I am very ambivalent about him.

The rational scientific manager in me is very impressed with the results Gujarat has delivered. It is not a fiction. The fact is those are real results from the ground. Not just a PR wash.

Enough people from all sides have told me -- and I have seen the figures, planning commission data.

But on the other hand I do feel we can't -- if he had apologised or shown remorse or if had been that kind of thing -- I think one could have reconsidered (one's assessment of Modi).

My other problem with Modi is that he is very good and he has delivered very good governance, but he has done it purely by the strength of his personality.

What we need are institution builders. So my ideal prime minister is one who would reform institutions. I don't think what Modi has done (can be sustained after him by) the next person (because he has not built institutions).

No one can follow in his footsteps? Like Indira Gandhi, he did it with the strength of his personality?

Yes, he did it through the force of his personality. Of course, Indira Gandhi has done a lot of destruction. But he has also done destruction.

But I have to say I am still ambivalent, because you can't wash away or brush away a tremendous track record.

This is the kind of track record we want for India today. What Gujarat has achieved, that's what India needs today.

Please click Next to to read why the middle class is one of India's greatest strengths...

You can buy India Grows at Night at the Rediff Bookstore.

Anna Hazare and an unlikely band of revolutionaries

When you read about America in the early 1900s, there was a lot of lawlessness and corruption. Institutions were not strong. Big businessmen were making money in ways that were not always desirable.

A lot like what is happening in India today. Do you think it is a matter of time for India to get to the point where America is today

Yes, I think that is probable. That is what is probably happening. We are going through a robber baron phase.

America's industrial revolution took 150 years and both India and China have condensed that in the last 30, 35 years.

America grew at three percent per year. We are growing at eight percent, China is growing at 10 percent or has grown at 10 percent.

So compared to (America's) three percent, seven percent is very much higher. So it won't take us 100 years.

It is a matter of time. It is a matter of also getting the right people who will do the reforms. You have to be lucky.

I also think technology is in our favour. One hundred years ago America did not have the kind of social media, the middle class, the television, the Internet, what the middle class is using, to force reforms.

China is also going to find the same thing. The biggest enemy of China's Communist Party is the Internet. A lot of the discontent that is there is being registered. People have a way.

This is why they say the follower has that advantage. The pioneer takes much longer. The follower takes the technology.

You mentioned you don't see any good leaders on the horizon. Living in Delhi and in the circles you may move around, there may be some promising leaders you have interacted with or heard about.

I have met some impressive youngsters who certainly seem very good. They have the right ideas. Younger politicians. And even a few older ones.

The problem is this: You need to have some track record to judge the person by.

Is that the same problem with Rahul Gandhi?

He doesn't have a track record.

In fact, some chief ministers have good track records. Nitish Kumar has a good track record. Modi has a good track record in a half way, in terms of governance and the economy, but he is not acceptable.

I think the Madhya Pradesh chief minister is quite impressive, (Shivraj Singh) Chauhan. He is an impressive guy.

I hear from people who run companies and industries in Madhya Pradesh. As far as governance and economy is concerned he has a good track record.

Perhaps the strapline of your book -- A Liberal Case For A Strong State -- conveys the message you would like to bring across through this book. In case not, what is the most important message that you are trying to convey through this book?

What I want to convey is that more important than economic reforms today more important is the reform of our institutions.

In Nehru's time we were very proud of our institutions -- the judiciary, the police, the civil service. The fact is 40, 50 years later these institutions have gotten weakened and frayed and we have to reform them. That is why I say that India has to grow during the day. India grows at night is not sustainable.

A Chinese friend of mine said to me that the nightmare of the Chinese, the Communist Party, the Chinese government, is that India became the second fastest growing economy in the world with one hand tied behind its back.

The nightmare of the Chinese leadership is what if that second hand got untied.

So the race between India and China is not (about economies). The race is if India will fix governance first or China will fix its politics.

An excerpt from Gurcharan Das's India Grows at Night on the strength of India's middle class:

I first met Shashi Kumar in early 2000. He was twenty-two and had just joined a business process outsourcing (BPO) call centre in Gurgaon. He came from a tiny village in Bihar; many of his friends at work did not know that his grandfather had been a low-caste sharecropper in good times and a day labourer in hard ones.

They had been so poor that on some nights they had nothing to eat.

Somehow his father had escaped from bondage and found a job in a transport company in Darbhanga. Since they could not manage on his father's salary, his mother had gone to work. She taught in a tiny school in their neighbourhood where she earned Rs 400 a month, and she would take him with her to the school, where he was educated for free under her watchful eye.

Determined that her son should escape the indignities of Bihar, she tutored him at night and got him into college. When he finished, she presented him with a railway ticket to Delhi.

Ten years later Shashi Kumar had risen to a middle manager position, and exuded the self-assurance of a young man with a future. He earned Rs 65,000 a month and spoke confidently in English to customers in America.

He lived in a two-bedroom flat, which he had bought four years ago with a mortgage from a private bank. He drove a nice car and sent his daughter to an expensive private school. He had just returned from an assignment in Boston where his company had sent him for training at their customer's office.

'It's a good time to be alive,' said his mother, who has been living with him in Gurgaon ever since her husband died. 'I don't know how he managed it. I just saved a few paise each day and gave him a railway ticket. He did the rest.'

Shashi Kumar had turned out to be an affable, diligent young man. What made his life different from those of the previous generations was a real sense of life's possibilities.

He was a product of the new middle class, the fastest growing segment of Indian society.

Had his grandfather dared to dream of another kind of life he would have been beaten up by his landlord in Bihar.

Before 1991, there had been little possibility of upward movement. The only way to break into the middle class was to get a government job, which was not easy. So, if you got educated and did not get a job, you faced a nightmare that was called 'educated unemployment'.

'Now anyone can make it. All it takes is basic education, computer skills and some English,' said Shashi Kumar.

'But why have these jobs not come to Bihar?' asks his mother mournfully. Her son had the answer.

'I am a Yadav, and so was Lalu,' he said, referring to Lalu Prasad, the former chief minister of Bihar who was apparently of the same caste. 'You educated me, but Lalu did not educate Bihar. He dismissed computers as toys of the rich and kept his people backward. Eventually, he realised his mistake. By then it was too late.'

Last year I ran into Shashi Kumar on the spanking new platform of the Guru Dronacharya station of the Delhi Metro. I was surprised to see him in a Gandhi cap. He was surrounded by friends from his middle-class neighbourhood in Gurgaon and he introduced them enthusiastically. They also wore the same cap.

All winners in India's economic rise, they were headed for the Ramlila ground where Anna Hazare was holding another anti-corruption rally. They looked an unlikely band of revolutionaries.

With good jobs and nice families, they lived in comfortable flats in Gurgaon, drove cars and sent their children to good schools. What were they doing waving flags on a platform of the Metro line between Gurgaon and Delhi?

Shashi and his friends belonged to the new middle class, which voted daily in the bazaar but hardly ever at election time.

India's middle class had great economic clout in the marketplace but that did not seem to affect the nation's political life where the countryside still determined the outcome of elections. The power to consume had got divorced from political power, and looking at them I wondered if this was about to change after Anna Hazare.

Shashi Kumar explained that his modest turn to political activism began with Ruchika Girhotra. He was acquainted with her family -- they had come from Chandigarh on a visit to his neighbour's home. He was vaguely aware that her case had languished in the courts for almost two decades.

When the verdict finally came, and he saw it on television, he was outraged and he wanted to do something.

The train came and we squeezed in. A young man got up and made a place for me. I smiled at him, happy that some of the old courtesies of the road persisted in the razzmatazz of a rising India. The young men found places near me.

One of Shashi Kumar's friends explained that all these years they had been intent on their careers and had had no time for anything else until Anna Hazare roused them.

'We hate politics and politicians,' added Shashi Kumar. 'They remind me of everything ugly in Bihar. So I never vote. I wouldn't matter anyway.'

'But why Anna?' I asked.

'What has attracted me to Annaji,' answered his friend, 'is his belief in dharma-centred leadership. To make a politicial revolution you have to first make a moral revolution within yourself. When citizens are moral they can make their government listen to their demands.'

I was moved by these Gandhian chords in the speeding Metro train.

'I don't know if anything will change, but at least I will be able to tell my grandchildren that I was there when history was taking place,' Shashi said.

I rose to leave as my station was approaching. Shashi and his friends were continuing towards Ramlila Maidan. We agreed to meet the following weekend when they were planning to attend another Anna Hazare rally.

'Annaji woke us up,' shouted Shashi form the train.

Anna Hazare had also woken up India's political establishment. No one could remember a time when so many powerful political figures were in jail. Some of the credit belonged to Anna's anti-corruption crusade.

Shashi Kumar and his friends were on their way to support his second hunger strike in August, which he staged in Ramlila Maidan. It drew tens of thousands of supporters and this show of strength forced the government to reconsider a strong version of the Lokpal bill -- a considerable victory, since politicians of all parties had stonewalled the creation of an anti-corruption agency for forty years.

Extracted from India Grows at Night by Gurcharan Das, Penguin India, with the publisher's kind permission.

You can buy India Grows at Night at the Rediff Bookstore.