| « Back to article | Print this article |

Guantanamo: Justice paused, shackled

Showing up for a hearing at the United States military court in Guantanamo Bay in Cuba is an ordeal for the detainees and a logistical burden for the American military, which has to transport the terror suspects from the detention facility to 'Camp Justice' inside the US Naval base in Cuba.

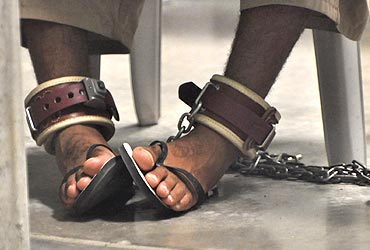

High-profile detainees like Ibrahim al Qosi, accused of helping the Al Qaeda chief Osama Bin Laden, are brought to the court house shackled, wearing earmuffs and blacked out sun glasses for the hearings which are proceeding at snail's pace.

According to this correspondent who recently visited the infamous detention centre, the small holding room where suspects are kept before the trial has a toilet, a chair with chains grounded to the floor and an arrow pointing to Mecca -- if the prisoner wants to pray.

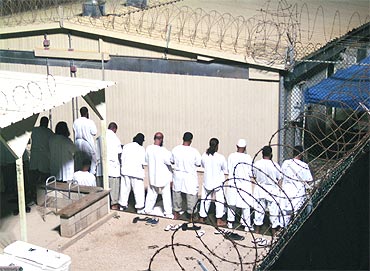

From 2002 to 2008, a total of 779 detainees have passed through Guantanamo Bay detention centre set up by previous Bush administration to try the Al Qaeda terror suspects after the 9/11 attacks.

Text: Betwa Sharma

Click NEXT to read why Obama's promise remains unfulfilled..

Obama's Gitmo promise remains unfulfilled

United States President Barack Obama, however, wants to shut down the detention facility, which became notorious after it was revealed that the detainees there were abused and assaulted.

Last year, Obama signed an executive order to close down the detention facility by 2010 and transfer prisoners to jails in the US or in foreign countries.

The detention camp, however, remains open.

Besides Al Qaeda propagandist Ali Hamza al-Bahlul Ali of Yemen, Australian David Hicks who fought alongside the Taliban, Osama's Sudanese driver Ibrahim al Qosi, Salim Hamden from Yemen -- were also tried by the military commissions.

Al Qaeda propagandist Ali was sentenced to life imprisonment in 2008.

Under trial, under pressure

The guilt plea by al Qosi, accused of helping Osama escape from US forces in the Tora Bora mountains of Afghanistan, led to the first conviction of a Guantanamo Bay detainee last week under the Obama administration.

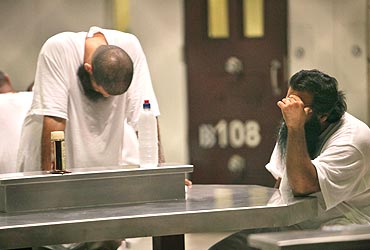

But al Qosi, who pleaded guilty, is only the fourth man to be convicted since prisoners first came to Guantanamo in 2002.

In June, Noor Uthman Muhammed, another Sudanese accused of being the deputy commander of a terrorist camp in Afghanistan, skipped his hearing at Guantanamo Bay where the defence pleaded with the judge to appoint a psychologist to examine the mental state of the defendant.

A pre-trial hearing for Noor, at the end of June, lasted for approximately an hour and the next court session was scheduled for September.

Military Judge Captain Moira Modzelewski from the US Navy remarked that it would take her several months to read the paperwork on the case.

Three out of the 181 "unprivileged belligerents", who were previously called "unlawful combatants," are currently under trial.

'Gitmo cases should be transferred to federal courts'

The sluggish pace of the trials, set up under the Bush administration, has reinforced the position taken by opponents of the military tribunal that detainee cases should be moved to federal courts.

The military, however, insists that it takes time to tackle the new problems emerging from terror trials.

"There are novel legal issues in these cases," Director of Operations of the Military Commissions Wendy Kelly told PTI.

"It can take the same time to get a complex criminal case from indictment to trial in a federal court," he added.

'Gitmo cases lack transparency, fairness'

Human rights groups fear that the "war on terror" could be a long-term excuse for deflecting the route of federal courts.

They further assert that the military trials do not have the same degree of transparency as civilian courts, which are backed by established legal codes and procedures.

"We're going backwards," said Adam Abram, the director of Human Rights First, noting it was unnecessary to make up new laws now. "It doesn't have a ring of fairness."

The Military Commissions Act 2009 passed under the Obama administration beefed up protection of the detainees but it still falls short of the safeguards of a civilian trial.

Noor's lawyers, for instance, are currently arguing that a psychologist is needed to determine the mental state of the defendant who has been in prison for eight years where he probably made statements after being subjected to harsh interrogation methods.

"The exact number of interrogations is unknown to the defence," reads the legal brief, noting that the records were "woefully deficient" and defence team had not been allowed to meet Noor's medical providers who failed to treat his chronic pain.

"The government has redacted Noor's medical records to conceal the identity of the providers and steadfastly refused the defence requests to access these individuals," said the legal document.

'Harsh interrogation raises serious doubts'

Ahilan Arulanantham from the American Civil Liberties Union pointed out that a judge of a civilian trial would not accept statements made by the accused even if there was a slight chance that the evidence was obtained by torture or mistreatment of the prisoner.

"Given that he was probably subjected to harsh interrogation raises serious doubts about whether these statements were made voluntarily," he told PTI.

"If you think about it, it is more and more disturbing," he added.

Arulanantham, director of national security at ACLU of Southern California, underlined that in a civil court even the inability of the prisoner to refuse answering his interrogators would make the statements involuntary and inadmissible.

Besides Noor, the commission is also hearing the case of Omar Khadr, the Canadian who was sent to Guantanamo Bay when he was 15-years-old in 2002.

Five more cases will hit the docks soon, including that of Nasir Ahmad Nasir al-Bahri, a former bodyguard of Bin Laden, who is accused of having a role in the attack on the navy ship, USS Cole, in 2000 in Yemen.

In the past year, 24 more detainees have been charged and the cases of 45 more are being reviewed.

The US Congress is unlikely to close Gitmo

The uncertainty about the camp's future impacts the progress made by the commissions since the military is not sure if or when it would have to wrap up operations.

But at the same time, there is a growing perception that Obama's promise will remain unfulfilled because the US Congress is unlikely to close Gitmo.

Arulanantham noted that the military trials gave the false impression of being normal court proceedings.

"There is much less transparency and part of the reason is that the infrastructure of the court is still not in place," he said.

Several significant facts in the legal documents of Noor's case, for instance, were redacted.

"He has been subjected to various forms of (redacted) over the course of several years," read the document.