| « Back to article | Print this article |

Green debate: Plaster of Paris Ganesh will stay

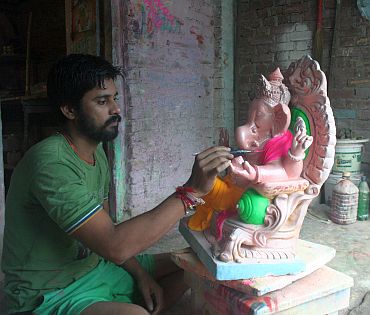

The use of Plaster of Paris to make huge Ganesha idols has been a bone of contention amongst devotees, organisers and ecologists. Abhishek Mande travels to Pen, where the Ganesha making industry finds itself entangled between faith, business viability and environmental concerns. First of a two-part series:

Raju Panse is on his motorbike carrying a large jute bag that looks suspiciously empty. The bike splutters to a halt in a square surrounded by a cluster of houses.

Panse is not amused. He doesn't like to be stopped in the middle of the road, especially when he carries that sinister-looking jute bag with him.

But his neighbours will have none of it. They rib him, beg and plead before him and insist that the bag be opened. Panse tries unsuccessfully to wheedle his way out.

By now a small crowd has gathered -- everyone wanting to see the contents of the jute bag. Finally Raju Panse gives in and a king cobra emerges from out of the bag. Wielding it with a stick, Panse puts up something of an impromptu show.

Amidst the awe of seeing a snake, someone says something about feeling blessed -- having spotted a king cobra during the holy month of Shravan. Had it been Nag Panchmi, the day when snakes are worshipped in India, Panse would have been a bigger hero. And the snake would have been made to drink milk -- a ritual that many ecologists cringe at and have been screaming hoarse against for generations.

This scene is unfolding in the small town of Pen, about 80 km from the island city of Mumbai, known for its Ganesha making industry, which itself has come under fire from environmentalists.

What the environmentalists say

The bone of contention has been the use of Plaster of Paris in the making of Ganesha idols.

Environmentalists insist that the material has been causing substantial damage to the eco system in general and the marine life in particular as larger than life Ganeshas are immersed in water bodies at the end of the festival.

The Central Pollution Control Board has also asked public ganesh mandals to return to the 'Vedic roots'.

According to the recent guidelines, the CPCB has suggested that the Ganeshas be painted in water soluble and non-toxic natural dyes.

PoP is a threat to marine life

"The use of toxic and biodegradable chemical dyes should be strictly prohibited," the guidelines read.

Sruthi Subbanna a research associate with an NGO called Environment Support Group says that PoP is not a naturally occurring material and it takes several months for idols to dissolve completely.

Subbanna also informs us that PoP reduces the oxygen levels in water and chemical elements such as sulphur, phosphorus and magnesium in the plaster and mercury, arsenic, lead and carbon in the dyes used to paint the idols result in the death of marine life too.

The paint in the idols ends up in our food chain

The Bengaluru-based microbiologist who has earned her degrees in environmental pollution control from Universities of Mumbai and Oklahoma adds that is isn't just the idols that pollute the water at this time of the year: "Several decorative accessories used during the Ganesh Puja like cellophane, plastic flowers, cloth, incense, camphor and numerous other materials are dumped carelessly adding more strain to the already polluted rivers and lakes."

Another line of reasoning comes from Dr T Venkatesh, principal advisor, Quality Council of India, who pointed out, "Once the idol is immersed, the paint dissolves into the water. Animals and fish drink this contaminated water that eventually ends up in our food chain through milk products or meat."

Either way, it is no secret that for at least a week there is a thick layer of PoP floating in the sea along the Mumbai coast.

Pen presents a different side to the debate

On days following the immersion, which is an almost continuous process through the ten-day festival, mutilated Ganeshas are scattered on the beachfront.

Harm to the environment apart, it certainly doesn't present a pretty picture for those who happen to visit the beaches around this time of the year.

Most of these idols are made of PoP. The clay ones would have already been dissolved by then.

At Pen though you see a different side to this debate.

There is much that remains to be done

Sixty-four-year-old Chandrakant Dhamne, who was part of the 'snake gathering', shuffles his way to his workshop where hundreds of Ganeshas sit in various stages of completion.

The D-Day is getting closer and there is much to be done. Dhamne is a simple man with little needs.

He lives across the road from his workshop. His house with four rooms is home to his wife, three sons -- two of who are married and one who has a kid -- and at least a few hundred Ganeshas.

During the festivities -- after all the Ganeshas have been packed off to their destinations -- Dhamne clears out his living room.

He gets it painted and welcomes the elephant-headed god, one that he crafts himself.

Dhamnes make about 8,000 idols a year

For the Dhamnes, Ganesha making is a family business.

All the men are involved in the job -- Dinesh, the oldest of the three works as a security guard in a local bank but takes a month off before the festivities to help out his father and brothers complete the orders.

In Pen, idol making is a year-long job.

Between themselves Dhamnes make about 8,000 idols each year. They pool in their talent and hire labour to meet the demands.

Their Ganeshas go to neighbouring districts as well as to larger cities such as Mumbai.

This is the only business they've known of

Once the Ganesha festival is over, they move to making idols of Durga and Amba -- for Navratri, the festival of nine nights celebrating, like all Indian festivals, victory of the good over the evil.

33-year-old Dinesh Dhamne says their family wasn't always into this business.

"My father had a grocery shop that ran into losses. 22 years ago he decided to start making Ganeshas. We've been in this ever since."

Incidentally, none of the three Dhamne brothers are very highly educated.

Dinesh, for instance, hasn't completed his schooling. This is the only business they've known.

PoP Ganeshas are more in demand than clay ones

Most of the Ganeshas they make are of PoP. With a readymade mould, they are simpler and faster to make.

Moreover, PoP Ganeshas are much more in demand than their clay counterparts.

"They (PoP) cost less, are easier to transport and relatively less prone to breaking than clay. Also it is not possible to make Ganesha out of clay beyond a certain height. Where as you can see PoP idols towering over 20 feet in Mumbai," he says.

Chandrakant Dhamne points out that it also helps them keep up with the demand for Ganeshas.

"Between ourselves, we can make over 50 to 60 Ganesha idols of PoP in a day. If we have to make it with clay, we cannot go over 15 at best."

Despite the demand, they somehow eke out a living

This increase in requirement, Dhamne says, started around 1995 and has been on the rise ever since. The use of PoP he adds also rose from that point in time.

Despite this upward trend, Dhamne, like quite a few other Ganesha makers in Pen, just about manages to eke out a living.

That's because like almost everyone else in the town, he borrows money from the local bank -- at a rate that ranges anywhere between 12 per cent and 18 per cent -- and repays it towards the end of the year.

The cycle follows the next year and so on.

A ban on PoP will bring down revenue

On most occasions he is able to make a decent sum -- between Rs 2 lakh and Rs 3 lakh and feed his family.

If he is lucky, he even makes some profit.

At other times when he is unable to break even, the overdraft is carried forward starting a vicious cycle that takes years to come out of.

A ban on PoP will mean the likes of Dhamne will not be able to make as much money as they do now.

It will also mean that families such as this one will be forced to look elsewhere for a source of income, perhaps even uproot itself from Pen and head towards the neighbouring metropolis of Mumbai.

What the pollution control board says

Some of the Central Pollution Control Board guidelines include:

- Encouraging the use of baked clay over Plaster of Paris

- Use of water soluble and non-toxic natural dyes to paint the idols

- Removing all the worship material like flowers, vastras (clothes), decorating material (made of paper and plastic) etc. before the idols are immersed.

- Cordoning off and placing a synthetic liner at the bottom of 'idol immersion points' The liner will have to be removed on completion of immersion ceremony so that remains of idols would be brought to the bank.

- Making local bodies responsible for appropriately disposing off the leftover material at idol immersion points within 48 hours of the immersion.

- Making public aware of the ill effects of the toxic components of colouring material not only of the idols, but also other decorating materials used during the festive season.

Watch this space for Part-II of the series...