| « Back to article | Print this article |

Give the military veterans their due

Wonder whether the sight of military veterans protesting governmental injustice will prick the national conscience, asks M P Anil Kumar.

I had just landed at the base camp of Siachen Glacier for my stint as the Forward Air Controller. A subedar hustled to the captain of the helicopter, implored him to evacuate a havildar in his early thirties to the army hospital at Leh. The bawling of the havildar was intermixed with howls of him seeing only white all around.

I learned from the medic later that his terrible condition was caused by overexposure to the combo of intense ultraviolet rays at high altitudes and glare rebounding off the snow. He added the havildar was lax in protecting his eyes with goggles, he could not be evacuated in time because of inclement weather, and he thought the retinal burn had become irreversible.

Two weeks later, I temporarily shifted base to Kumar -- named after the veteran alpinist Colonel Narinder Kumar. Another jinx: A pallid, wan major was being evacuated to the base camp. He and his detachment were manning a crucial 21,000-feet-high post on the Saltoro Ridge. Elemental fury claimed all his three subordinates, but the helicopters could not make it because of impenetrable clouding.

By the time he was rescued, frostbite had laid waste his hands and feet, starvation had enfeebled him and the loss of his men had transformed him into a wreck. His expressionless face said it all. All his frostbitten fingers and toes would be amputated at the Leh hospital.

It was February 1986. Since neither could continue in service because of physical disability and blindness, both the major and the havildar would be discharged from the army on medical grounds some time in 1987. That meant another battle, a lifelong one, with life itself.

M P Anil Kumar is a former fighter pilot. He contributes a regular column to Rediff.com

The government practises 'soft apartheid'

Since they cannot find alternative employment, the government pays them what is called disability pension -- an amount parsimoniously calculated by our babus to help them make both ends meet, but not live a life of dignity as a former Indian soldier who unfortunately fell by the wayside.

Since they were involved in Operation Meghdoot (the military action we launched in April 1984 to regain and hold our territory on the Siachen Glacier), the army would declare the major and havildar as war casualties, and the two would get war injury pension.

What would the major and the havildar get as war injury pension today? The major Rs 17,742 plus dearness relief (DR), and the havildar Rs 10,520 plus DR (hereafter, DR needs to be added to the figures mentioned as pension). However, if they hadn't suffered disability in a war zone, the major would be eligible for disability pension of Rs 11,862 and the havildar Rs 7,010.

Mind you, the two were struck off the rolls in 1987. Now suppose a major and a havildar with the same years of service (6 and 14, 15 respectively) were discharged in 2010 on the same grounds. How much would each draw as war injury pension?

The major Rs 36,410 and the havildar approximately Rs 14,800. (In case of disability pension, it would be Rs 16,905 for the major and approximately Rs 7,940 for the havildar.) Too many numbers, but I hope you are still with me.

We can make the following observations from the above:

The government practises 'soft apartheid'. When the cost of living is same for both, why should personnel getting disabled in wartime and peacetime be treated differently for pensionary benefits? A life of disability is a life of disability; the context of the injury should not matter.

The government needs to ensure parity while fixing pension among a class of its employees, to provide for a certain standard of living of all parties. I believe peacetime disabled soldiers deserve to be paid as much as the wartime ones, but the war disabled must be paid a large sum as compensation.

Two soldiers of the same rank and same service getting disabled two and 25 years ago receive different amounts as pension. The major gets just 49 per cent of what his 2010 counterpart gets as pension. Similarly, the havildar gets 71 per cent of his 2010 counterpart.

IAS babus deny veterans their due

Given the unique rank-based hierarchy and service conditions, and early retirement, rank-based 'military pension' was instituted as recompense till the Second Pay Commission, but the Third Pay Commission overturned the policy and equated civil and military pension.

Ever since, the military veterans have been demanding 'One Rank One Pension' (OROP). It implies the rank and the length of service must be the sole determinants of calculating military pension. The date of retirement should not figure in the calculus. Like, the major and havildar of 1987 must get the same war injury pension as the pair of 2010.

The OROP argument has been won by the veterans -- including securing the imprimatur of the Supreme Court and the approbation of the leading lights of political establishments. (To know more about OROP, please read my article The government cons the military, again.)

However, as is their wont, the IAS babus -- the self-appointed arbiters of what's good for you and me, the wellsprings of enlightenment and wisdom -- throw a monkey wrench into the works by rehashing the defeated counterpoints, over and over, just to deny the veterans their due. Spite.

The games babus play

As for our governments, it won't be an exaggeration if I say the tail wags the dog -- the ministers rubber-stamp what the IAS babus decide. Doesn't matter if the Peter Principle (in a hierarchy every employee tends to rise to his level of incompetence) has overtaken the now totally corroded 'steel frame'.

Though it defies reason, though the recommendations of the Sixth Central Pay Commission (SCPC) did not make any such distinction, why the disparity in the amounts of old and new pensioners? Our 'creative' babus created the division. They decreed that those who retired before January 1, 2006 (the day the SCPC awards came into effect) would be an underclass of pensioners drawing only a percentage of what those retired on/after January 1, 2006 -- the upperclass -- was bestowed by the SCPC.

But wouldn't such a division pigeonhole the bureaucratic nobility too? Don't worry, our babus know how to skim the cream off!

The Cabinet secretary and the secretaries tap the same pension scales irrespective of their date of retirement (people in the know will tell you that unless vigilant citizens like Prashant Bhushan get them implicated in serious crime through the courts, the system has been artfully manipulated to enable all IAS officers to reach secretary level without exception!). To dispel the impression of them having and eating the cream, they have served some stuff to their equivalents too.

But why have the rest of the pensioners been denied their due? Soft apartheid!

The government being a government, has to be two-faced

For example, while the SCPC acknowledged and retained the rank structure of the defence services within the four pay bands by referring to 'bottom of the rank pay band' to compute pension, the babus sank 'rank' sans a ripple, and implemented the rest of the phrase -- 'bottom of the pay band'.

Consequence: Sepoys to havildars who put in 17 to 21 years' service will take home pension equivalent to one year's service. Boo!

Anomalies and oddities galore, but the troubling issue is: How can a committee of secretaries mutilate those recommendations of the Pay Commission that were unpalatable to the IAS? Nature of the beast.

Pension scales must be unitary, and as I argued earlier, the amount of pension fixed must enable the entire lot belonging to a class recognised by the government to lead a certain standard of life.

Instead of tying in knots to justify the unjustifiable, the government would have become a model employer if it had devised a unitary pension mechanism.

The SCPC muddle only amplifies the call for OROP, for OROP is built on the bedrock of equity.

Pallam Raju, the minister of state for defence, informed the Lok Sabha on April 21, 2010 that 'the government would not be able to meet the 'one rank one pension' demand due to administrative, financial and legal implications.'(You don't have to be a genius to demolish the stock administrative-financial-legal contention.)

But wait. The government being a government, has to be two-faced if it has rejected anything. Lately its functionaries, despite the ministerial assertion, are claiming that they have nearly implemented OROP for junior commissioned officers and other ranks, and would soon surprise the officers with similar benevolence.

Sheer sophistry, as believable as the government's trumpet to fetch the filthy lucre stashed in foreign vaults!

The veterans feel they have been outflanked, and boxed in

While drafting the AFT Act, 2007, the babus ensured that the Tribunal was not vested with the powers of civil contempt. (The Contempt of Courts Act of 1971 defines: civil contempt essentially means wilful disobedience to any judgement/order, wilful breach of an undertaking, etc, while criminal contempt means scandalising the court, lowering its authority, obstruction of the administration of justice in any manner, etc.)

Without the power of civil contempt, the AFT cannot call to account the government (read babus) for temporising or not executing its orders. (Interestingly, in a proactive interpretation, a division bench of the Kerala high court has told the AFT to take coercive action for non-implementation of its orders by treating it as criminal contempt. This is bound to be challenged in the Supreme Court.)

Here's the long and the short of it: If the babus thumb their nose at the AFT, the AFT can only wink at that gesture. Spite, again.

Contrast this. Section 17 of the Administrative Tribunals Act -- the Central Administrative Tribunals for the babus draw power from this statute -- capacitates the CATs with full powers of contempt!

The other recourse, the Armed Forcers Grievance Redressal Commission, has only a recommendatory role, not adjudicatory teeth. Which means we are back to square one: The validation of the commission's pronouncement will be the prerogative of a babu! (While every babu isn't unresponsive or a stonewaller, the service not short of officers with positive outlook, the SCPC and OROP experience does not inspire the veterans with confidence in the bureaucracy.)

The veterans feel they have been outflanked, and boxed in. The only avenue left is to protest against the injustice, adopting the same badge of decorum they lived by while donning the uniform.

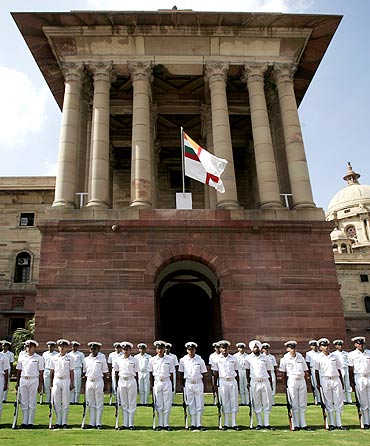

On March 6, aggrieved military veterans will hold rallies in different cities to highlight three primary issues: Denial of OROP, disregard for widows' entitlements and non-implementation of AFT orders. In the capital, they would submit a memorandum to the President, signed in blood.

Forsaken, at the Supreme Commander's doorstep

The veterans had sought the President's availability, several times, to personally hand over the memorandum and deposit their medals.

This time too, citing unavailability, the President's office has detailed an officer to be the receiver. Unlike last time, the veterans have decided not to hand over the medals to the President's staff.

The last time, the official refused to accept the memorandum signed in blood, I believe, for the fear of getting infected! Well, it's okay when the same blood is spilled while battling the nation's enemies.

Whenever I read about the American president, qua commander-in-chief, walking that extra mile to embrace and empathise with the veterans, I naturally wish for the Indian President emulating him. What a world of difference that would make. The Supreme Commander surely can be more than a complaint box.

Veterans and a government caught up in jobbery

In Greek mythology, Zeus sentenced Sisyphus to roll a huge boulder up a steep hill, but it would always roll down just short of the peak, forcing him to start all over again! Though there is a Sisyphean parallel, Sisyphus' struggle seems like a stroll today if one compared it to the Indian military veterans' tortuous toil since 1983 to obtain OROP.

I doubt whether even an unfeeling government would let things slide so much as to compel the country's military veterans to take it to the street.

Can the military veterans stir the present dispensation, widely perceived to be, uncharitable though, a government of the corrupt, by the corrupt and for the corrupt?

I believe that any nation that yearns to fulfil the aspirations of its people needs two emotional nutrients: Sense of pride and sense of shame. A sense of shame to prick the national conscience to set right the wrongs and the inequalities. These could be slavery, dehumanising caste stratification, discrimination, institutional apathy or even indifference to people simply because they cannot collectively bargain with their employer like the soldiers who surrender their fundamental rights.

Wonder whether the sight of military veterans protesting governmental injustice will prick the national conscience. Jai Hind!