Photographs: Fayaz Kabli/Reuters Aasha Khosa in New Delhi

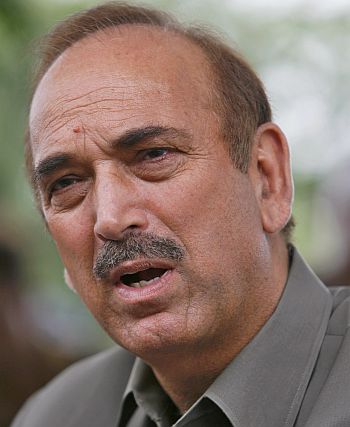

It was the United Progressive Alliance government's second term and a meeting of the Cabinet was about to begin. Virbhadra Singh, Vilasrao Deshmukh, Farooq Abdullah and Mamata Banerjee flanked Health and Family Welfare Minister Ghulam Nabi Azad.

Before the meeting actually started, Azad took the microphone and told the prime minister: "Sir, this is the former chief ministers' club in your cabinet." Everyone smiled except Banerjee who protested that she was not a former chief minister, to which Azad quipped: "Don't worry, you can sit here, you are a future chief minister."

Azad's jokey claim to membership of a 'chief minister's club' was something of an irony. Today, within weeks of that cabinet meeting, he is stuck with an administrative public health challenge few health ministers have faced: The outbreak of the H1N1 swine flu virus. The crisis is so acute that Azad could be excused for wishing he was back in the happier climes of Jammu and Kashmir, although that was not his first priority in 2005.

A Congress insider's biggest test

Image: Prime Minister Manmohan Singh with Azad an election rally in Khundroo, 90 km south of SrinagarPhotographs: Danish Ismail/Reuters

His disinclination to do so stems from that fact that throughout his career as a politician he's tried to distance himself from the region in which he grew up and lived.

From Doda in Jammu, Azad, a post-graduate in zoology, is from one of those relatively rare Muslim families in J&K that do not belong to the valley. He has consistently tried to ensure that politically, he is not identified with parochial interests, seeking instead a national, "Indian" image.

In party circles, he continues to contradict those who introduce him as former J&K chief minister -- he says he is a national leader.

A Congress insider's biggest test

Image: Congress president Sonia Gandhi listens to a Kashmiri as Azad watchesPhotographs: Danish Ismail/Reuters

He was handpicked by Sanjay Gandhi to head the All India Youth Congress in 1980 -- at 30, he was the first Muslim and the only Kashmiri to head the organisation.

Since then he has been a member of the Rajya Sabha for several terms, but almost always from some state other than his own. He represented Maharashtra in the Lok Sabha.

Because of his anxiety not to be identified as a Kashmir leader, Azad used the Congress party to establish his national political credentials -- emerging, over the years, as a powerful Congress leader.

There is no other AICC general secretary who has served six terms. Few know that when the Congress first came to power in 2004, Azad remained a member of the core committee (the innermost party-government group) even after he became chief minister and would fly back from Kashmir for every meeting until he was politely told he didn't need to do so.

A Congress insider's biggest test

Image: Demonstrators throw stones at a Rapid Action Force soldier during a protest in Jammu against the government's decision not to give forest land to a trust that runs Amarnath cave shrinePhotographs: Amit Gupta

Azad wanted the Amarnath Yatra, a trek revered by Hindus, to take place along a modernised track and to that end, transferred government land to the Amarnath Shrine Board.

The opposition led by the People's Democratic Party objected to this move, charging that this could influence the ethnic character of the state, where Muslims are in a majority in the valley.

The order was then revoked leading to protests by the Hindus. His government had to quit and J&K came under President's rule.

His adversaries thought this was the end of Azad's political career, but he bounced back with his party's victory in the Assembly election and was back in Sonia Gandhi's "core" team of advisors.

A Congress insider's biggest test

Image: A woman carries her daughter as they wait for a H1N1 flu screening at a hospital in New DelhiPhotographs: Fayaz Kabli/Reuters

If the Amarnath incident was his first career-threatening move, how he handles the swine flu scare could well be the next.

There has been criticism of the way he has handled the epidemic, but it is coming not from peers in the opposition parties, but people who have little idea of administration and less of politics.

While Indians have been warned against going abroad and thermal imaging systems are being put up at airports to detect the virus, not a single inbound foreigner has shown any signs of having the disease.

This probably means that most human beings are carriers, but fall ill because the virus affects individual immune systems differently. The answer to what helps the human body fight and defeat the attack can be discovered through a limited immunological study that entails a survey of those who are infected.

When the first few cases of swine flu were detected in India, Azad set up a core team of ministry officials -- which he now consults almost on hourly basis.

He began speaking to a group of epidemic specialists each morning before taking meetings of bureaucrats to tackle the swine flu. He now arrives in his Nirman Bhavan office at 8.45 am every day and works till 10.30 pm with a 90-minute break for a siesta.

A Congress insider's biggest test

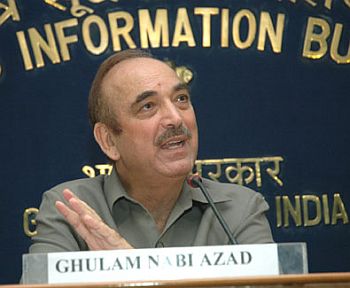

Image: Azad briefing the media on H1N1 in New DelhiPhotographs: Press Information Bureau

Not a single file is pending for his signatures in the office.

"The minister makes it a point to clear 200 to 300 files per day, and nothing is kept for the next day, especially after the swine flu outbreak," a close aide said.

History will judge whether Azad has been a good health minister or a bad one.

He already has a tough act to follow in his predecessor Anbumani Ramadoss who, despite his high-handed behaviour with the director of the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, established a legacy as a successful anti-tobacco campaigner.

There is no doubt that Azad is trying hard to be an effective health minister.

But in a country in which public health infrastructure has been doing poorly for decades he has his work cut out for him.

article