| « Back to article | Print this article |

FLASHBACK! Highs and lows of India's foreign policy

The year 2011 saw various events -- the Arab Spring, anti- corruption protests, Europe's sovereign debt crisis -- transform countries and reshape the world order. Gateway House, a leading Mumbai-based think tank on India's foreign policy, takes a look at what these events mean for India, and presents India's top foreign policy cheers and jeers for the year.

2011 was the year of transformation, everywhere -- the extraordinary Arab Spring, anti-corruption protests around the world, the assassination of Osama Bin Laden, NATO military drawdown from Afghanistan and Iraq, the Fukushima nuclear disaster, the sovereign debt crisis in Europe...the list is long. All this unaddressed by lackluster leadership in India and abroad.

The events that captured India the most were the stunning spread of the Arab uprisings, to our West, and the accelerating geopolitical aggression of China, to our East. Also significant was the unraveling of two optimistic economies -- the United States and India, both victims of internal political dysfunction.

The new world order is upon us, forcing nations to reorient their policies. Many have been pro-active -- like Germany, Brazil, Australia and Canada. And India? Bedeviled by slowing growth and lack of reform, a collapsing industrial sector, departing foreign and domestic investment and increasing inequality, we have missed the opportunity to shape the global re-ordering. India looks like it belongs in the crumbling Eurozone instead of the vibrant emerging markets of Asia.

Evidence of the decline of the India story: in 2010, the presidents of all five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council visited us; last year, no one came. The arrogance of 9 per cent GDP growth has been replaced by the gloom of less than 7 per cent growth.

Certainly, India has also seen some foreign policy. We present our top foreign policy 'cheers' and 'jeers'. Read on!

Please click NEXT to read further...

Cheers to the matured anti-corruption movement

The Anna Hazare-led anti-corruption movement in India, converted the angst of its dormant middle class into significant street protest starting in April.

With a clear appeal against the paralysing graft eating into the nation, this is the movement of a mature democracy, distinct from the Arab uprisings which are the first expressions of democratic aspirations.

The Occupy Wall Street protests which started in the US and spread worldwide, while commendable, have yet to establish a united demand.

The Hazare movement is a credit to an India in the throes of a self-cleansing process, it has raised our international stature, and spot-lighted us as a more 'open' democracy.

India-Bangladesh becoming congenial neighbours

The India-Bangladesh relationship is finally developing into one of congenial neighbours 40 years after India played a decisive role in the liberation of Bangladesh from West Pakistan.

The recent overtures came from Bangladeshi Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, who recognises the benefits of good relations with India. Her initiatives -- particularly in countering secessionist activity in India's north east -- were built upon by Prime Minister Manmohan Singh during his September visit to Dhaka.

He signed ten agreements including the sensitive one on the demarcation of borders, and the opening of river and road trade routes.

Sheikh Hasina's mature reaction to the tantrums of Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee, helped keep the new buoyancy intact.

Uranium, Australia's gift of friendship for India

Australia's lifting of the ban on uranium exports in December -- vital for India's energy requirements -- was a bold step in making that country a closer partner with India in the rapidly-changing geopolitics of Asia.

Australia is home to one-fourth of the world's uranium, and years of intense lobbying by India finally paid off. The announcement, made by the ruling Labour Prime Minister Julia Gillard, overturned her party's 40-year position on uranium sales to non-Non Proliferation Treaty signatory nations.

Significantly, both countries followed-up with military cooperation immediately after the announcement, and the Australian defence minister visited India just three days later.

IFS rises to occasion to rescue stranded Indians from Libya

India's envoy in Libya Ambassador M. Manimekalai executed the timely and smooth evacuation of Indian workers from Tripoli and elsewhere in Libya during the violent rebellion this March.

India's other ambassadors in West Asia conducted smaller, quick exercises from similarly revolting Arab nations.

Despite severe manpower constraints, the Indian Foreign Service rose to the occasion.

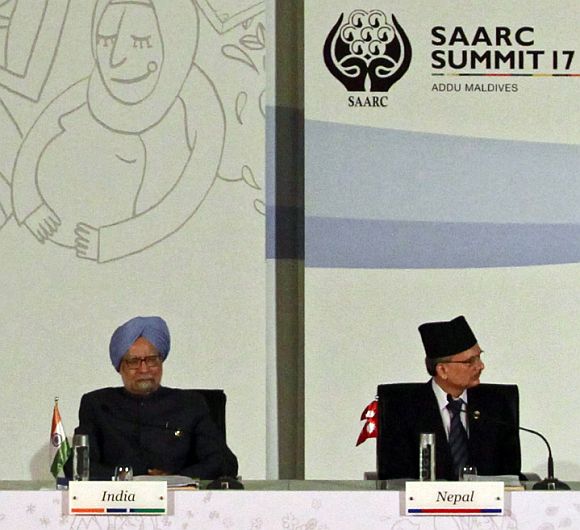

Nepal coming closer to India

The Nepal-India bilateral has advanced significantly. Nepal, like Bangladesh, has long been reflexively anti-India.

But in October, Nepali Prime Minister Baburam Bhattarai visited India and positively shifted the political discourse.

Trade took the lead; three major agreements were signed which will promote private Indian investment in Nepal. Like Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, who set a good example when he put his job on the line to push through the US-India civilian nuclear in 2008, so did Bhattarai with the India-Nepal trade initiative.

He was met with the same outcry at home, and saw similar success when the deal was signed. Anti-Indianism is losing its sting. Progress now, with almost all our South Asian neighbours -- leaving Pakistan isolated in its animosity towards India.

India increasingly explores business ventures in Afghanistan

Afghanistan is finally being seen as a business opportunity by India's private sector. In November, a consortium of Indian companies including Tata Steel and Steel Authority of India Ltd. won the $11 billion bid to mine iron ore in Hajigak in central Afghanistan.

Our soft power with our historical neighbour, formerly restricted to building schools, hospitals, power and technical training, now has another dimension: business.

This could bring us head-to-head with China, which is also buying up Afghan mining rights and building infrastructure.

But it strengthens our position in Kabul, which this year became our strategic ally.

Please click NEXT to see what were the LOWS of India's foreign policy in 2011

Jeers for Krishna's Portuguese mumble

Jeers for Foreign Minister S M Krishna, who read the speech of the Portuguese foreign minister at the United Nations Security Council Meeting in New York in February 2011, instead of his own.

It was not the finest moment for his foreign affairs aides, but it clearly reveals the extreme shortage of foreign service officers, which the government shows no signs of mitigating.

India has about 700 full-service diplomats serving 200 countries around the world. Compare with tiny Singapore, with 526 diplomats, Great Britian with over 8,000, the US with nearly 11,000 and China with over 30,000 not counting public diplomacy departments.

India hasn't capitalised on Pakistan's deteriorating ties with US

Pakistan -- we're still unable to insulate ourselves from the chaos within that nation, and have not substantially capitalised on its deteriorating relationship with the US.

While Prime Minister Singh is being statesman-like in reassuring Pakistan that India will not take advantage of its current turmoil, it is time for us to recognise that Pakistan is unable to respond to positive overtures due to the inherent handicaps of military domination and increasing religious fundamentalism.

Best for status quo powers like ours to watch and wait it out when it comes to our western neighbour.

India unable to elevate ties with US to the next level

The potential of the India-US relationship is stagnating. The 2008 civil nuclear deal, which elevated the engagement to the level of strategic partners, is fizzling out due to deliberate linguistic ambiguities in the agreement and the questionable future of nuclear power itself, post Fukushima.

We have been unable to take the bilateral to the next level, despite promises made during President Obama's visit last year especially with regards to India's permanent membership of the UN Security Council; instead we are once again faced with anti-India legislation from the US outsourcing lobby.

A visible indicator of disinterest: the year-long vacancy for the post of US ambassador to India, only recently filled by Nancy Powell.

This is in contrast to the immediate replacement of US Ambassador to China John Huntsman with Chinese-American Commerce Secretary Gary Locke.

China continues to unequally engage with India

China (like Pakistan and the US) is a prime example of inertia in our foreign policy. Our assertive eastern neighbour is rapidly expanding its influence across Asia.

While all Asian nations, apprehensive, are creating new alliances, India has been passive in ring-fencing China's aggression.

Our bilateral trade deficit is massive; still, like an undeveloped African nation, we continue to export raw iron ore to China even as our manufacturers are kept out of that country by non-tariff barriers.

Historical issues -- the border disputes, Tibet, the Dalai Lama -- remain, along with China's disdainful refusal to engage with us as equals. We continue to front for China in international fora like climate change and the Doha trade talks; in return, let alone the UN Security Council, we have not even been able to extract membership to the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, despite the support of old friend and key player Russia.

In the mad race for arms, India ignores poverty alleviation

In 2011, India became the world's largest importer of military arms -- accounting for nearly 10 per cent of global arms imports over the past five years -- overtaking China. In the same year, the UN's Human Development Index put India at the bottom of the list among nations with the largest population of the world's malnourished children.

Our policy response? An ever increasing number of leaky and scandalous government schemes like the National Rural Employment Gaurantee Act, the Food Security Bill, and the Unique Identity Card.

For 60 years, similar programmes have pretended to address the same issues. Despite 9 per cent growth, poverty has been decreasing by less than 1 per cent a year. This is hardly the model that we hope the world will emulate.