| « Back to article | Print this article |

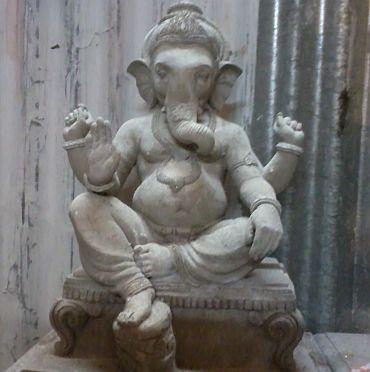

Eco-friendly Ganesha? What's that?

The use of Plaster of Paris to make huge Ganesha idols has been a bone of contention amongst devotees, organisers and ecologists. Abhishek Mande and Nithya Ramani find out that for the common man, it is more a question of faith and his pocket than environment when it comes to choosing his Ganesha murti.

Eknath Chavan came to Mumbai over 30 years ago. He left his village in the Ratnagiri district of Konkan because it offered him no opportunities.

Today, he works in a pharmaceutical company in the city's suburb of Goregaon and lives in a single-room apartment in one of the chawls in Lalbaug. Along with his wife and two children Chavan sets out each Ganesh Chaturthi to pick up the Ganesha he has chosen months ago.

The Ganesha is made of clay, is of a certain height and will occupy a place of pride in his home.

Chavan isn't someone who knows what it means to be eco friendly. He knows that clay dissolves in water more easily than Plaster of Paris, but that is not why he gets his Ganesha made out of clay.

Click on NEXT to read further...

Also Read: Green debate: Plaster of Paris Ganesh will stay

Why the Kadams opt for a PoP Ganesha

"Our murti (idol) is always the same. We have always bought clay Ganeshas. Thankfully we can afford it (clay)," he says rather simply, refusing to get into a debate on a topic he has no idea about.

Chavan's neighbour, Rupesh Kadam does odd jobs and lives in an apartment slightly larger than Harry Potter's closet. The 8x8 feet room houses him and his parents. ('My two brothers live elsewhere now,' he coolly says) And for five days a year, it also becomes home for a 10-inch-tall Ganesha.

Unlike Chavan though, the Kadams -- who run a tea stall -- cannot afford Rs 600 for a clay Ganesha every year. Yet they want to be part of the festivities.

So the refrigerator, the television set and the narrow bed are moved into the common passage area and a Ganesha made of Plaster of Paris is brought home with some amount of festivities.

In Kadam's apartment, I am made to feel at home. The fan is switched on; a glass of water is served. I am told I cannot leave without having a cup of tea. Some biscuits are offered, which I refuse and gulp the tea with a lump in my throat.

On asking if he ever thought of the harm his Ganesha can cause to the environment Kadam says he has no clue.

Some do it for tradition, others to save costs

The only visible 'polluting' element in his house is a second hand refrigerator that possibly emits CFC at levels that are almost negligible when compared with the high-rise office complexes with glass facades that have emerged down the road from his house.

He takes the public transport bus and the local trains. His father walks to work and so does his mother. What carbon footprint must this guy have, I wonder, and drop the idea of probing him further.

Yet the fact remains that there are many like Kadam who prefer to save a few bucks and go for PoP rather than clay.

Some do it in the name of tradition, others simply to save costs and even others because their Ganeshas have become too large for their own good.

PoP Ganesha: Commercialism to blame?

In Pen, there are a little over 500 factories producing Ganeshas. The makers themselves are in debate over the total number of idols emerging out of Pen. One Shrikant Chachad insists it is 30 lakh.

However, Shrikanth Deodhar, who comes from one of the oldest Ganesha-making families, pegs it at around 15 lakh. Both agree, however, that only five per cent of the entire produce is made of clay today.

"There simply isn't any demand," says Chachad, who has made about 28,000 Ganeshas this year all of PoP.

Dr Pradeep Tripathi, who runs a campaign called Go Green Ganesha, says that 'PoP idols are made only because people want it'.

He blames commercialism and the human desire to have everything larger than life as the root cause of the problem.

'Ganesh murtis are not the only things polluting Mumbai's water'

"The festival has become very commercial and Ganesh mandals are in competition about the height of their idols," he says over the phone.

Tripathi has a point. It is no secret that mandals are often known to be very touchy about the height of their Ganeshas.

The one in Ganesh Galli, established in 1928, has a Ganesha that is 22 feet tall since 1977. The nearby Parelcha Raja, which was first installed in 1947, has been 28 feet tall since 2001. In comparison, the famed Lalbaugcha Raja stands at a modest 12 feet -- a height we are told has been maintained since its inception in 1934.

Satish Khankar the president of Lalbaugcha Raja suggests that they have 'a status to live up to'

"We will not reduce the height. If people are so conscious of being eco-friendly, they should be asked to stop other means of pollution like vehicles. This is a divine matter and nobody should have a problem with God's idols. Ganesh murtis are not the only things polluting Mumbai's water," he argues.

'Activists are like frogs. They come out during rains'

Gurunath Kargaonkar, Vice President of the Ganesh Galli Ganpati Association also brings up the question of faith.

He says, "Clay Ganeshas cannot be made taller than five feet. There was the mandal in Girgaum that made a clay idol of 12 feet and it broke on its way to the sea. It is considered a bad omen and nobody would want to do that. Who wants such mishaps that would upset our devotion to the God?"

Kargaonkar continues, "Activists are like frogs. They come out during rains and create a ruckus and forget about it immediately. If people have so much of civic sense they should also practice it during the rest of the year. Why concentrate only on god's idol during Ganeshotsav? If they want us to use eco-friendly products, then they should provide us with it. Nobody knows where such material are available."

Tripathi hits back, saying: "There are 10 to 12 feet tall idols of Durga being made in West Bengal and Orissa. Their internal structure contains dry grass. The reason why mandals are orthodox is because every mandal has some political party backing it up."

Ecologists be damned! This is the season of faith

Shrikant Deodhar, however, points out to a very practical problem that Tripathi possibly doesn't see.

"There are very few artisans left. You need talent and an eye for creating those kinds of idols. Today it is all about mass producing Ganeshas," he says, adding that he is not sure how many factories would survive if PoP was banned.

As you step out of Deodhar's house, Kasar Alley -- the hub of Ganesha idols within Pen -- is chock-a-block jammed with cars, tempos and mini-vans. Here a labourer brushes off a speck of dust on one Ganesha. There another one gives finishing touches to the lord's feet.

Everyone waits patiently as elephant-headed gods are loaded with care, covered with plastic as it continues to rain incessantly.

A new crop of Ganeshas is ready, a market waiting to welcome the god. The gloomy mill workers' apartments in Lalbaug are transformed magically into fairytale lands, complete with snow and chariots. Ecologists be damned! This is the season of faith.