| « Back to article | Print this article |

'Dr Khorana never paid lip service to anybody'

In the fifth of the series on late Nobel laureate Dr Har Gobind Khorana, a student shares fond memories of his guru

Part I: Dr Khorana, Nobel laureate and one of science's immortals

Part II: Dr Khorana: 'Considerate, most remarkable man'

Part III: Dr Khorana: 'A loving father, a caring mentor'

Part IV: A Nobel laureate salutes another

If it were not for Dr Har Gobind Khorana, Dr Aseem Ansari, who studied at Mumbai's St Xavier's College, would have joined the Indian Navy following the footsteps of his uncle and mother, who was a professor at the Naval Academy.

Ansari, professor in the department of biochemistry at the University of Wisconsin in Madison and a member of the Genome Centre, said he was headed in that direction when as part of his college curricula he read various scientific papers by Dr Khorana.

"These papers along with a book on genetics by another author completely changed my life's goal and my future trajectory," Ansari explained.

A few years later, he came to do his PhD at Northwestern University. Sometime in the mid-1990s, Ansari had a chance meeting with Dr Khorana when the two of them were in an elevator at MIT.

"I could not speak for some time. Then I hesitantly introduced myself to Professor Khorana. He jokingly asked why I would not join his laboratory," Ansari recalled.

Although Ansari was never Dr Khorana's direct student, all his life he has meticulously read and studied the Nobel Laureate.

"I was like Eklavya -- learning from the guru from a distance," he said. "I did not cut my thumb, of course, but Professor Khorana inspired me so much!"

Since that elevator meeting, he met Dr Khorana several times and would see him at least once a year in connection with the Khorana Exchange Programme.

"Since the first meeting with him what struck me about him was that he was always very caring about people, including me, although I was not his student, and had always a very healthy curiosity about things and people around," Ansari said. "He never paid lip service to anybody and was earnest and sincere in whatever he did or spoke about."

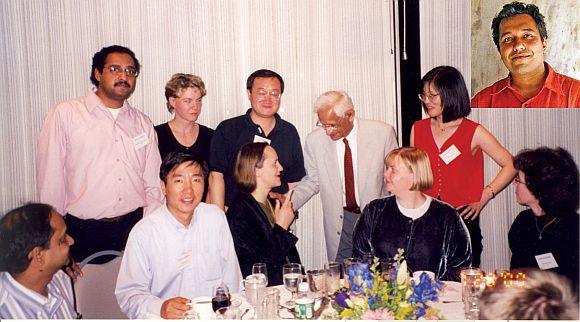

Ansari recalled Dr Khorana's sense of humour and ability to divert from serious scientific issues to small talk at informal gatherings.

Shiladitya DasSarma, professor of microbiology and immunology at the University Of Maryland School Of Medicine, who did his PhD in biochemistry at MIT, said Dr Khorana was a dedicated and patient teacher and mentor.

"I have fond memories of him from the many group meetings that he had nearly every day of the week and how he was engaged with the details of each of his students' and post docs' research," DasSarma said. "I felt privileged and honoured to be among the select group of graduate students in his group. I strongly believe he never lost his love of research and scientific inquiry."

He said Dr Khorana was an incredibly hard worker. "He had already won the Nobel Prize for his work to solve the genetic code when I worked in his group, but he was still highly dedicated to his research and group. He had group meetings every day of the week. He always made it worthwhile to come into the lab and made the research exciting. These meetings in my mind mark the beginning of the era now called synthetic biology," he said.

DasSarma said that unlike many others, Dr Khorana did not offer many traditional lecture courses. "So, I learned from his research meetings, which were on membrane proteins and nucleic acids chemistry and biochemistry."

Asked about his most lasting memory of Dr Khorana, DasSarma said it was when he worked with the pioneering scientist on research papers and proposals.

"He was very proud when I won the National Science Foundation graduate fellowship to do my PhD in his lab," DasSarma said. "We wrote three papers together in the 1980s for the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA with Professor Uttam L RajBhandary."