Photographs: Henning Stegmueller, distinguished still-photographer, cinematographer and filmmaker, Germany

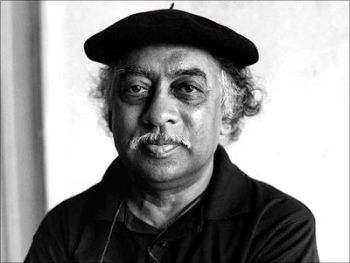

Legendary Indian writer, critic, painter, and filmmaker Dilip Purushottam Chitre passed away on Thursday.

We bring back to you an earlier interview with the rare multi-talented artist, who spoke about his passion, his work and his views on India's global reach to Rediff.com in 2007.

At the ripe young age of 16, Dilip Purushottam Chitre made a decision that would change his life forever. He decided he wanted to live as a poet and artist.

It could not have been an easy choice. He admits to vague premonitions of it being difficult, and admits it proved hard at times. And yet, after over fifty years of living that life of poet and artist, he stands by it, refusing to have it any other way.

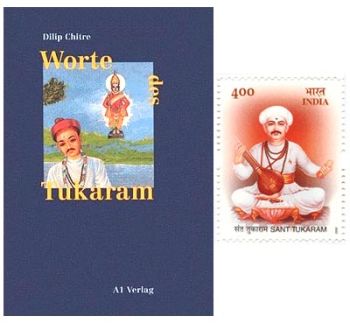

One can't blame him either. After all, his has been a life gifted with all sorts of revelations. It has been a colourful life, one spent whole-heartedly in the service of art and literature. His achievements, when strung together casually, boggle the mind. Chitre has -- since publishing his first collection of poems, Kavita, in Marathi in 1960 -- published a lot in English (Travelling in the Cage, 1980), has had his work translated into Hindi (Pisati ka Burz, 1987), Gujarati (Milton-na Mahaakaavyo, 1970), German (Worte des Tukaram) and Spanish.

He has exhibited his own paintings (First One Man Show of Oil Paintings, 1969); written and directed an award-winning film (Godam, 1984); made a dozen documentary films and scored music for some of them; taken on the mantle of editor for literary magazines (Shabda, 1954-1960); written for India's most respected publications; influenced a literary movement (the little magazine of the sixties in Marathi); convened poetry festivals; won all kinds of honours; travelled widely across India and abroad; and taught at universities worldwide.

So, when he describes his interests on his blog thus -- 'I am a poet and a writer. I paint. I make films. I travel. I make friends. I read. I listen to music. I reflect. I contemplate.' -- it's hard not to believe him.

Born in Baroda in 1938, Chitre soon moved with his family to Mumbai, where he published his first collection of poems. Possibly the most famous of his translations is Says Tuka, a rendition of the work of seventeenth century Marathi bhakti poet Tukaram. It is a translation of abhangs, a form of devotional poetry sung in praise of Vitthal. Chitre's translation continues to find new readers, surprising and moving them with its simplicity: 'There is a whole tree within a seed/ And a seed at the end of each tree/ That is how it is between you and me/ One contains the Other.'

I envy Dilip Chitre for the life he has lead, for his unwavering faith in all he holds dear. He now lives in Pune with his wife, Viju, to whom he has been married for over 45 years. 'Even in the most civilised societies of the world, poets receive ambivalent treatment,' he writes. 'The economic value of what poets do is considered extremely dubious...The most they can hope for during a lifetime is niche audiences scattered far and wide and small publishers crazy enough to publish poetry without any regard to sales.'

As Chitre prepares himself for new worlds to dive into, I asked him a few questions to help connect the dots so far...

Text: Lindsay Pereira

'Writing is an intimate dialogue'

Image: A painting by Dilip ChitreYou are among few bilingual writers who have managed to speak effectively in two languages. Kiran Nagarkar and Arun Kolatkar come to mind. Do you consider language at all when you start on a project, be it film or poetry?

I am pluri-lingual like many other South Asian writers I know. Kolatkar, Nagarkar, Vilas Sarang and Damodar Prabhu are what I would call my contemporary Anglo-Marathi writers. There are Anglo-Bangla, Anglo-Malayalam and Anglo-Oriya poets, among my contemporaries. Our individual histories as bilingual writers are very different though, if that matters.

As for me, I was born in a family of native Marathi speakers in Baroda, or Vadodara, in Gujarat and spent the first 12 years of my life there speaking four languages fluently: Marathi, Gujarati, Hindustani and English. My first three years of schooling were in an English medium school run by Jesuits and I picked up English from an Irish 'brother' among other teachers. I switched schools often. My second was a Marathi medium school where Gujarati was also a subject. Hindustani (the pre-partition lingua franca of Western, Northern, Central, and Eastern India) was another addition to my linguistic repertoire. I studied Bangla and Urdu out of curiosity.

From 13 to 22, I lived in Bombay/Mumbai. I finished high school, went to college, graduated with honours in English literature, worked as a college tutor and as a journalist, all before I was 22. I then married, published my first book of poems in Marathi, and went to Ethiopia to teach English in government high schools on a three-year contract. While there, I picked up the national language, Amharic, but have lost it since due to lack of practice. From 25 until the age of 37, I was again in Mumbai. In this period, I worked with corporates as well as NGOs, from a multinational pharmaceutical company to a cultural organization dedicated to civil rights, and from an advertising agency to freelancing as a translator, journalist and film scriptwriter.

This phase ended with my being named Creative Executive at the Indian Express Group of Newspapers. During the National Emergency of 1975-77, I kept my job with The Indian Express to take leave and join the International Writing Program of the University of Iowa in the US as an invited Fellow. I stayed on in the US till the end of 1977 even after my Fellowship tenure ended. For the next two years, I conducted creative writing workshops for schoolchildren in the public school system of Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

Language is the medium of all personal and professional relationships. Creative writing is an intimate dialogue between writer and reader, both of whom are imaginary to each other. The only real thing for each of them is the language that connects them. But language also connects one with one's inner self. It is our means of self-recognition through transient and tentative self-images. It is the core of both our spiritual and secular (or this-worldly) experience.

Marathi is my given mother tongue. English is my favourite other tongue. They don't divide me. I will not cohere without either of them. For that matter, Gujarati, Hindustani, Urdu, and all the other languages through which I am connected with the outer world as well as my own inner self matter equally to me. I have been writing poetry seriously since the age of about 16, when I took the momentous decision to live as a poet and an artist. I had a vague premonition it was not going to be an easy life. It did prove very difficult indeed, at times. However, my curiosity and the realm of human experience made my life an exciting adventure and I was rewarded, from time to time, by revelations that constitute the core of my work, the insights that made it worthwhile to be a poet and an artist.'Mumbai became a metaphor for the larger world'

You published your first collection at 21, nine years after your family moved to Mumbai. Did the city have anything to do with your need to express yourself through poetry?

Poems in my first Marathi collection were written between the ages of 15 and 21. They begin with my experience of my uprooting from my native Baroda. I entered Mumbai when I attained puberty. Simultaneously, Mumbai entered my poetry. Being a precocious reader, my grounding in literature was wider and deeper than my academic upbringing, and often at variance with it. I was passionately interested in music, photography, drawing, and painting since the age of 10. In Mumbai, I had opportunities to mingle with artists, musicians, film technicians and photographers much older than I.

I met Pandit Sharadchandra Arolkar, an outstanding vocalist of the Gwalior Gharana at age 16. I was a daily visitor to his home in Shivaji Park until I left for Ethiopia. He was a profound influence on my ideas of art, not just music. Mumbai figures in my early Marathi and English poetry in different ways and at several levels. I perceived the metropolis in juxtaposition with primordial nature as perceived in my childhood. There was a discord. There was a sense of manmade alienation that haunted me.

Though most of my early poetry is metrical and sometimes stylised, it was spontaneous and unpremeditated. The big city's polyphony, its cacophony as well, its many human voices and points of view, made me move towards more accommodative, open-ended, cadenced free verse and the rhythms of colloquial speech. My early poetry was sensuous, erotic, and exuded a kind of sexuality that was instinctive and natural to me in my youth. Yet, I felt I was being robbed of my youth itself by the big city where human values come to die, lured by its opulence and glitz. A political awareness of this process followed slowly, but surely. Mumbai became for me a map and a metaphor for the larger world. It prepared me for all the later big cities in my life: Chicago, New York City, Los Angeles, San Francisco, London, Paris, Moscow, St. Petersburg, Berlin, Tokyo and Hong Kong, for example. All of them had something of Mumbai in them.

In my later poetry, many of these other cities figure because I write poems instead of an autobiographical journal. They are not travel notes though. Cities in my work connect with all the major themes of life and death, though the countryside is equally present. My first Marathi collection of poems was published in 1960. My first collection of English poems came out 20 years later, in 1980. But all through this period, I wrote simultaneously in both languages; and not just poetry. I wrote fiction, plays, essays, film scripts and criticism as well.

What kind of impact, according to you, did the little magazine movement in Marathi have? What do you think it changed?

Arun Kolatkar, Bandu Waze, Ramesh Samartha and I launched the first Marathi little magazine devoted exclusively to poetry in 1954. From 1955, we published it irregularly in mimeographed form. We collected money from friends and the magazine was distributed free to all public and college libraries in Maharashtra whose postal addresses we could collect. It reached poets and readers of poetry in many remote towns and cities and created the first 'network' of its kind in Maharashtra.

Little magazines heralded a change in literary sensibility and in the politics of literary taste. They also promoted alternative perspectives to politics, culture, and society. It was only a decade after Shabda -- the poetry magazine we launched in 1954-55 and ceased to publish in 1960 -- that the movement gathered momentum. Literary historiographers often ignore the time lag and treat it as though it was a continuous movement with one single agenda. Little magazines of the late 1960s and early 1970s had political rather than literary orientation. Marxist and Dalit magazines provide examples. They were also clique or coterie publications that did not attempt to reach and awaken new readership.

With only a limited number of pages per issue, they could publish mostly poetry, critical commentary, and short pieces of fiction. It was only in the 1990s that the movement was revived by a new generation of poet-editors. Today, there are at least four little magazines in Marathi regularly published from different cities in Maharashtra.

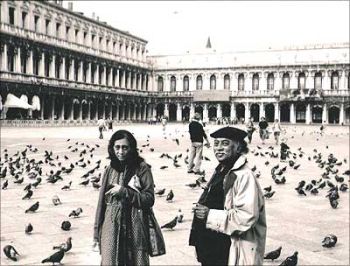

Image: Dilip and Viju Chitre at the Piazza San Marco, in Venice

Photograph: Henning Stegmueller, Munich, Germany. Stegmueller and Chitre wrote a screenplay based on Anita Desai's Baumgartener's Bombay that has a scene in Venice; the project was abandoned but Stegmueller insisted on taking the Chitres to Venice while they were visiting Germany.

'Writers flourish in the right milieu'

You participated in a writing program in 1975. Today, these programs have proliferated, with almost every major school abroad offering one. Do you think a program can actually create a writer?

I participated in the University of Iowa's International Writing Program in 1975-76 when its founder, the American poet Paul Engle, was still at its helm with his Chinese-born novelist wife, Hua Ling Nieh. Paul has died since and Hua Ling retired. The IWP is now directed by the poet Christopher Merrill and, from what I gather, the nature of the program is altered.

When I was there, the IWP invited as its Fellows creative writers (and occasionally critics and translators) who were established as major writers of greater promise in their language and country of origin. Many of my contemporaries there have won greater exposure and recognition since. We did not take classes in creative writing. We presented our own work to the other Fellows, faculty and students of the Iowa Writers Workshop, and faculty and students of the Department of Comparative Literature and Translation Studies. It was then open for discussion. We were free to do our own thing and to interact with our international and American counterparts -- an unforgettable and enriching experience.

I wonder whether the generalised view you imply of 'such workshops' can be compared with the IWP, then the world's most unique writing program of its kind. It brought together writers from Asia, Africa, Latin America, Eastern and Western Europe, Australasia, and North America who looked at one another's work as what Paul Engel memorably called a 'community of imagination'. It was an opportunity to discover deeper similarities that connected creative writing across apparently dissimilar cultures, traditions, societies, and political and economic conditions.

A writer creates herself or himself on the foundation of innate needs and capacities. Having said that, I must add that, like all fine artists, writers flourish in the right milieu. Today's painters, for instance, are not the prehistoric, self-taught artists of rock and cave paintings such as those of Bheembetka or Alta Mira. Even artists of tribal origin today enter the mainstream of civilisation one way or the other. We see reproductions, visit museums and art galleries, attend concerts and listen to lectures and demonstrations of music from the world over, see cinema from other countries, read books in their original languages or in translation. All this is education; it is not something at the obviously pragmatic level of a refresher course, a coaching class, a workshop, or a seminar addressed by some celebrity.

Writing can be developed in a serious, structured manner, too; the crucial factor is the teacher and her or his ability to bring the best out of individual talent each student must already possess. You can't teach creative writing to a wrong bunch of students; you can start teaching how to read creative writing for a start. Listening and reading skills are indispensable in a creative writing course. You can train people to respond to language in new ways.

Image: Dilip and Ashay Chitre (Chief Assistant Cameraman to Govind Nihalani) on the sets of Godam, 1983; Ashay was Dilip and Viju Chitre's only son. Born in Addis Ababa in 1961, he died of accidental asphyxiation in 2003. He was a victim of the 1984 industrial catastrophe in Bhopal, that cut short his promising career in cinematography and filmmaking.

'I am not a lyricist on a ramp'

After 50 years of being a poet, do you still feel the same enthusiasm for the genre? Are you still compelled to create poetry with the same vigour?

This is like asking me if I have any interest left in life after having already lived for more than 68 years. Poetry expresses one's perception of life and one's interest in its unfolding. Although much of my work focuses on anxiety, doubt, anguish, pain and suffering, it has never pre-empted joy, satisfaction, peace and a sense of fulfilment. Tragic and ironic modes of experience combine or alternate with comic, absurd, or outrageous attitudes to one's own passage through life.

As a poet, one is looking for a felicitous word or phrase, an outstanding line, a musical rhythm that is rich and surprising, a theme that encompasses human truth -- with the keenness of a bird looking for worms every morning. A bird that has aged too much, of course, loses appetite or becomes too weak to feed itself. My creativity in poetry or in the other things I still pursue hasn't reached that point yet. I was never compelled to create poetry. I felt free not to write even 50 years ago when I started. Self-expression takes forms of its choice. When I don't write, I draw and paint. When an opportunity opens up, I make a film or get involved in someone else's projects that appeal to me. When I am not doing original writing, I translate other people's writing and that is as creative a challenge as any. Creativity is an occupation, absorption; it is active awareness that seeks periodic cessation and renewal. It follows a certain rhythm inherent in one's character.

I will stop writing when I can't; or it would be more correct to say I wouldn't begin to write unless I felt I was ready to take the plunge again. 50 years seem small when one feels and thinks with the same intensity and perhaps with sharper focus. My best is still to come, though my worst is not yet over. That is my way of looking at it.

Poetry appears to have lost its importance in India today. While there were a great many experimenting with form as recently as 10-15 years ago, today's poets find no publishers or platforms for expression. Do you agree?

Importance for whom in India? Poetry matters to those who read and write it, reflect on it, and their number (like all numbers in India) is on the increase. True, the consumerist middle and upper class in India whose lives begin in shopping malls and end in tastelessly opulent living rooms don't buy or read books of poetry. For them, poetry is a celebrity mushaira or a cultural festival where it is important for them to be seen.

I am not a lyricist on a ramp or a cocktail circuit genius. I am not a best-selling author. For that matter, poets anywhere in the world are not. However, I don't share the bleak view that poetry is a dying art with little or no audience. Audiences do still gather to listen to a poet reading his work. Some of them buy books and even seek autographs. They are a minority in a culture of loudmouths. But their listening skills ensure that culture will live among those who value their own sensitivity and its reach.

Image: The cover of Bombay, Mumbai: Bilder einer Megastadt von, by Henning Stegmueller, Dilip Chitre and Namdeo Dhasal

'My work will find its audience'

The idea of a poet is now more of a media construct. If one gets a collection published by a minor publishing house and then mentions being a poet a couple of times, the media is quick to accept it, with no reference to the actual quality of work, and no critical evaluation of it. Does that bother you?

The media represent the invisible few who influence and shape public opinion. However, public opinion on that scale is irrelevant to the understanding and appreciation of poetry or any other fine art at the frontiers of creative excellence. It does not bother me. My work will find its audience despite the media simply because I expect my audience to be mature, sensitive, and cultivated at their own initiative.

How alive is poetry in India's regional languages? For instance, do you foresee the publication of another anthology of Marathi poetry documenting the last decade or so?

The poetry scene in Indian languages is incredibly alive. Our unique oral traditions have nurtured poetry for several centuries, so even first generation literates from amongst tribal and 'backward' communities keep surprising us with stunning poetry, the like of which nobody had seen in print before. Poetry has a deep connection with individual human rights. Among exciting new poets, many are women, and a few are gay or lesbian, or marginalised in other ways. Dalit poetry has opened the eyes of many tradition-bound, orthodox and academic readers of poetry to the innovativeness and sheer creative energy of the oppressed. An anthology of Marathi poetry of the last decade is already available in translation. It is titled Live Update! and has been edited and translated by Sachin Ketkar and published by Poetrywala, Mumbai. There are several anthologies, with many more to come in the next decade.

Your translation of Tukaram continues to find an audience. What makes him so powerful, more than three centuries later?

Says Tuka was published first in the Penguin Classics Series in 1991. I have since rescinded my contract with them and another edition was brought out in hardcover as well as paperback a few years ago. It nearly sold out without any hype. My translations are already included in an anthology of world poetry published in the US, and a German translation by Lothar Lutze was published by A1-Verlag. Mexican poet-translator Elsa Cross translated Tukaram into Spanish using my English versions as her source. All this is due to the classic appeal of Tukaram -- the inherent greatness of his poetry.

Image: The German translation of Chitre's poems, Worte des Tukaram; an Indian stamp featuring the seventeenth-century poet

'The West isn't open to translations yet'

Are you still interested in cinema as an art form?

I was, am, and will always be interested in cinema as an art form and much more. I made my first film on an 8-mm Kodak camera at age 10. Ever since I was a college student in Mumbai in the late 1950s, I hung around Bombay Film and Sound Laboratories, Famous Studios, Ramnord, and Rajkamal Studio where I made friends with technicians to learn about editing, recording, re-recording and mixing. I was a keen photographer. I got a chance to make advertising films in the late 1960s and, from the 1970s, have been making independent documentaries until now.

The only feature film I could make so far was Godam (1983). It won the Jury's Special Award at the Festival of Three Continents, Nantes, France. My filmography and videography includes a range of work, including commercial cinema. To make a film the way I like, I would need a producer who believed in me 100 per cent, or a sponsor with faith in my creative ability. I would not waste time hawking projects or promoting myself among speculators and gamblers who don't know cinema as a serious art form.

At the Kitab festival recently held in Mumbai, you spoke about whether regional writing appealed to a limited audience, and how migration affected writers and writing. What did you want to get across, to the audience attending that discussion?

Being primarily a poet and a translator of poetry and fiction, I was interested in finding out if British publishers, editors and literary agents were really interested in translations from South Asian languages. The point I was making about migration was that it was the key factor in globalisation. People migrate; writers migrate; books migrate. Why don't translations migrate to the same extent? The answer was obvious. Minds in the West that hold all control over English-language publishing aren't yet open to translations from Indian languages, despite the fact that our formidable sized middle-class speaks English as a second language and constitutes a growing part of the global market for English books.

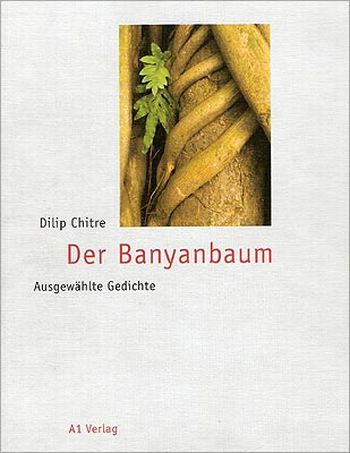

Image: The cover of Der Banyanbaum Ausgewahlte Gedichte (The Banyan Tree: Selected Poems) translated from English and Marathi by Lothar Lutze and published by A1-Verlag, Munich, also the publishers of Kiran Nagarkar's fiction in German

'Namdeo Dhasal is a major twentieth century poet'

You have three books being published in the first half of 2007, with more manuscripts coming soon. What are you most excited about?

The books being published are Namdeo Dhasal, Poet of the Underworld: Selected Poems (1972-2006); As Is, Where Is: Selected English Poems of Dilip Chitre (1964-2006); and Shesha: Selected Marathi Poems of Dilip Chitre (1954-2004). There are four other manuscripts waiting to be edited and structured for publication, as well as ongoing creative work and translation projects. I prefer not to talk about them now.

Why did you decide to translate the work of Namdeo Dhasal and Hemant Divate?

Namdeo Dhasal is a younger contemporary and, in my view, a major twentieth century poet of global stature. I have been translating his poetry since before his first collection was published in 1972. This book is the outcome of all I have been doing for about four decades. I decided to translate the entire first collection of Divate's Marathi poems because they have significance beyond Marathi in a globalizing world. His poems are consistently good and the book makes a coherent poetic statement about life in Mumbai since the 1990s. It reveals a disturbed and disturbing microcosm and the poems can withstand translation.

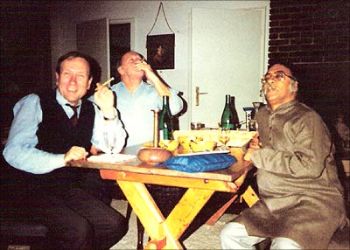

Image: Gunther Sontheimer, Lothar Lutze and Dilip Chitre photographed by Beatrix Pfliderer. The late Dr Sontheimer was a legendary Indologist who taught comparative religion at the University of Heidelberg; Professor Lutze taught modern Indian literature at the same university and 'opened the doors of Germany' for Chitre. Sontheimer and Chitre collaborated on the English translation of songs by the bards of Lord Khandoba, Maharashtra's ancient folk deity.'India is like an athlete with gangrene'

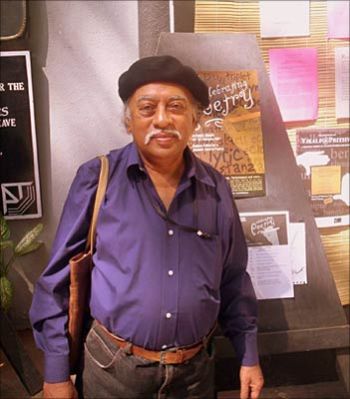

Image: Dilip Chitre at the Prithvi theatre during the 2007 Kitab festival in MumbaiYour early writing met with much criticism, mostly negative. Kiran Nagarkar recently spoke of similar attacks when he first strayed from Marathi as his language of expression. What is it about writers who break free of linguistic constructs that brings on such anger? Are you suddenly regarded as traitors of some sort?

My early writing broke away from that of my immediate precursors. The hostility it aroused in them was the establishment's response to anything that's new but can't be ignored because it catches the attention of even their own readership. Unlike what they did in Nagarkar's case, nobody (except a contemporary I shall not name) ever accused me of being a traitor to Marathi. I wrote and published in Marathi as well as in English. There was no question of abandoning one in favour of the other. My writing has not depended on any pampering by publishers, critics, or readers. I appreciate the response I get from the few who see something of value in what I do. As a poet, I am used to the notion of a limited audience. Novelists crave larger audiences, dream of living on royalties or advances on their future work, and I sympathise with them.

Much of your work, and that of your colleagues such as G N Devy, has attempted to draw India's attention to its dispossessed tribal communities. Does that battle still rage? Are you satisfied with what has been done so far?

G N Devy is an academic turned full-time activist. The Adivasi Academy founded by him in Tejgadh, Gujarat, is now doing something unique and historic. Devy was inspired by the work of Mahashveta Devi, the great fiction writer and fighter for tribal rights. I am not in their category. I am primarily a poet and an artist, and occasionally a thinker. I support activists, activist organisations, and any person or institution that attempts to empower the marginalised.

The dispossessed in India comprise as much as 30 percent of our population and 300 million would make a nation by itself. The hyped image of upbeat India at the beginning of this millennium is an illusion: India is more like an athlete with gangrene. Recently, during a lecture in Europe, I described India as 'not a waking giant but perhaps only a delinquent monster' for ignoring its dispossessed.

article