| « Back to article | Print this article |

China's latest stand: Take down tensions with India

It appears India and China have decided to step back and take a deep breath, writes Shyam Saran.

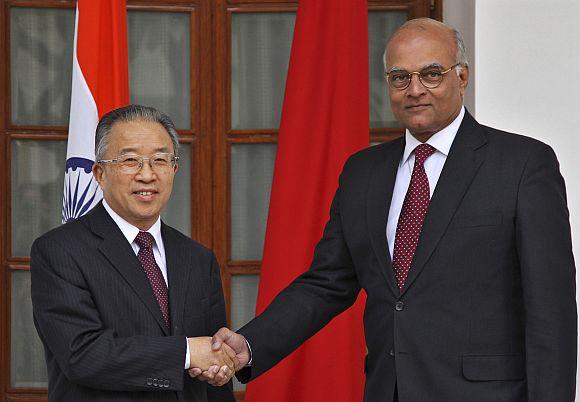

By the time this column appears in print, the 15th round of talks between the Special Representatives of India and China, Shivshankar Menon and Dai Bingguo, is likely to have concluded on an expectedly positive and forward-looking note.

The much awaited bilateral mechanism at the Joint Secretary level, to deal with any border incidents, is being put in place. This was proposed during Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao's visit to India in December 2010.

Substantive progress on the comprehensive resolution of the border issue was not anticipated, but over the past several rounds these talks have invariably covered a whole range of regional and global issues as well.

They have provided a platform for the two sides to exchange perspectives on such issues. This is important precisely because the two countries are emerging powers, whose respective strategic profiles are expanding and intersecting at multiple points -- particularly in Asia.

These intersecting points can become either new areas of cooperation or, conversely, additional areas of confrontation and even conflict. The SR-level talks help, therefore, in managing a rapidly evolving and complex relationship.

The writer, a former foreign secretary, is currently chairman of RIS and a senior fellow at the Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi

Click here for more Realtime News on China-India relations!

Please click NEXT to read further...What explains this somewhat unexpected turn of events?

What is noteworthy is that both sides seem to have decided to take a step back from their recently somewhat tense and even prickly encounters, draw a deep breath and reset relations towards a more positive course.

Both governments made an unusually well-orchestrated effort to create a congenial ambience for the talks, despite a clear awareness that the boundary issue is likely to remain unresolved in the foreseeable future.

The Indian and Chinese SRs used embassy events, in Delhi and Beijing respectively, to deliver speeches evenly matched in friendly sentiments.

Dai Bingguo went one step further, penning an article in the The Hindu on the eve of his visit, to pledge everlasting friendship and a "golden age" in India-China relations.

What explains this somewhat unexpected turn of events?

One, on the Chinese side, there is concern that its more assertive posture of the past couple of years has triggered a rapid and continuing build-up of countervailing coalitions in the strategic Indo-Pacific theatre, in which the US has taken the lead with its "pivot" into Asia.

While the Kuomintang's victory in Taiwan's recent elections may have brought some relief to an anxious China, this is counterbalanced by the death of Kim Jong-Il in North Korea, which left his untested heir holding the reins of power.

Preventing the still loose and essentially hedging coalitions from congealing into more open containment of China is an important objective. A more friendly and benign approach to India, which could be a significant "swing state" in this as yet fluid landscape, would serve this objective.

China concerned over negative developments in Pakistan, Myanmar

Two, the Chinese are concerned about negative developments in two key allied countries, one to the west of India and the other to the east -- Pakistan and Myanmar, respectively.

The deepening political and economic crisis in Pakistan and the deepening loss of control by the Pakistan army and the Inter Services Intelligence -- including over Jihadi elements that are feeding unrest among Muslim Uighurs in China's Xinjiang province -- mean that a mainstay of China's proxy containment of India is becoming problematic. The rising tensions between Pakistan and the US add to these worries.

On the other flank, China cannot but be nervous about the rapid political changes in Myanmar, which, at the very least, threaten to dilute China's 20-year pre-eminence in that country.

From a potential pressure point on India from the east, Myanmar could well turn out to be a pressure point on China from the south. Add to this the continuing unrest in Tibet, spawned by a growing number of self-immolations by Tibetan monks, and it is easy to see that in a year of sensitive leadership transition, caution, prudence and risk avoidance must be the watchwords for China's foreign policy.

Both India and China face difficult economic situation

Three, both India and China face a difficult economic situation domestically, which may be further exacerbated by the possible collapse of the euro zone, an energy crisis brought about by continuing political turmoil in the Arab world, and the possibility of an armed conflict involving Iran.

While India may find itself in a more favourable position vis-a-vis China geopolitically, it is like China, constrained by a worsening global economic situation and an incipient energy crisis for these reasons.

These two factors do provide a point of convergence between the two countries and a possible platform for coordinated diplomacy.

The forthcoming Brics (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) summit, to be held in Delhi in March, could help mobilise the most important emerging economies and Russia towards averting an Iran-related crisis. Dai Bingguo and Shivshankar Menon may well be playing the friendship flute together with an eye on the summit as well.

India misses an opportunity

Last, but not the least, is the rising political uncertainly in both countries. In China, there is the pre-arranged passing of the baton from the current generation of leaders to a new set of younger, though experienced, technocrats.

This will be a collective leadership -- but, precisely for that reason, it may find it difficult to deal with new and unfamiliar challenges both at home and abroad.

In India, political uncertainty is mostly self-inflicted. There is a real danger that if and when multiple economic and energy crises do erupt, the ship of state may not have a united, capable and strong captain and crew to lead it to safety. A risk-averse polity can at best welcome the relief provided by a more preoccupied China. It is unable to leverage this to significantly expand its own strategic space. A pity indeed.