| « Back to article | Print this article |

The Bo Xilai I Met

He was once tipped to be one of China's NextGen leaders, someone who would guide the Middle Kingdom's future for the next decade, once the present leadership retired.

In a dramatic saga, unparalleled in contemporary China, Bo Xilai suddenly fell from grace these past weeks, dismissed from all positions in the Communist party, his wife now accused of murder.

Nikhil Lakshman, who met Bo a few times, recounts those encounters with a Chinese politician like none other in recent Chinese history.

"Come," he said, inviting the group of Indian journalists out to the balcony of his office.

Until then we had no idea that Bo Xilai, then the Mayor of Dalian, the model city in northeastern China, could speak English.

Like many Chinese leaders before him (the legendary Zhou Enlai being the most famous) who gave no indication that they understood or were fluent in English, Bo had sat through an interaction with Indian editors accompanying President K R Narayanan to China, waiting for his interpreter to translate our questions, responding to our questions in Chinese, outlining his vision for his city in almost bored detail.

I had been intrigued by the choice of Dalian as President Narayanan's first port of call after meeting with Chinese President Jiang Zemin in Beijing.

The choice, I was told, had been determined by Rashtrapati Bhavan (after all, Narayanan was a former ambassador to China and a learned observer of the Middle Kingdom) and the Indian diplomats then posted in Bejing (brilliant men like Vijay Nambiar, now UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon's chief of cabinet; Gautam Bambawale and Venu Rajamony, currently joint secretary (East) at the ministry of external affairs, and joint secretary, economic affairs, at the finance ministry respectively, among others).

Dalian was perceived as one of the fastest rising cities in China and its leader Bo a future star of the Communist party leadership in Beijing.

Over six feet tall and handsome, Bo had yet to reveal the charisma I encountered six years later when he visited Mumbai. But the flamboyant showmanship he would flaunt in Chongqing, which so irritated China's current bland twosome Hu and Wen and played some part in his downfall these past weeks, was evident that June morning in 2000 when he led us to the balcony of his office, overlooking Dalian's main park.

Turning to his crouching aides -- in the supposed bastion of egalitarianism, feudalism and obsequiousness were always apparent -- he clicked his fingers, and as we gaped, voila!, music began to ring through the park, turned on by a switch in Bo's office.

"Mozart, Beethoven, Bach..." Bo smiled, could be played in the park, perhaps in harmony with his mood.

Only once during our chat with him had Bo appeared animated. This was when we asked if Dalian was off limits to outsiders.

In views that would probably cheer the younger Thackerays, Bo said only immigrants from other parts of China who had work permits were permitted into the city; those without such documents were ejected from Dalian's precincts.

Jiang Zemin -- whose craggy, smiling, face popped up all over Dalian, in apparent violation of the Communist party's edicts against explicit personality cults -- overlooked such administrative capriciousness.

It was left to his successor Hu Jintao and Premier Wen Jiabao to rein Bo in, and that only when he threatened the transition to China's next generation of leadership.

But that was all in the future. Bo's hospitality, and an evening of food and song beckoned.

Please click Next to read further about the fall of Bo Xilai, a case like none other in contemporary China

Bo liked drama

Invitations to the banquets on President K R Narayanan's trip were allotted by seniority. The younger journalists in the media delegation were presumably deemed to lack the gravitas needed for the banquet President Jiang Zemin hosted for his Indian counterpart in Beijing, so we were invited to the food-and-song fest Mayor Bo Xilai staged in Dalian two days later.

As we were ushered to our seats in what I recall was a baroque hall, a wizened old lady came by, accompanied by a young woman. As she greeted us with a Namaste and began to speak, the coin dropped.

This was Mrs Kotnis! Guo Qinglan, whom Dr Dwarkanath Kotnis had married in November 1941. The memory still gives me gooseflesh nearly 12 years later.

As we gathered around the widow of the legendary symbol of Sino-Indian friendship, the President and his entourage, accompanied by Bo, arrived.

For the next 90 minutes or so, as we feasted on some exquisite Chinese dishes (there was, of course, this one Indian scribe who insisted on an omlette instead of the fare provided, so we enacted an elaborate comic pantomine with the wait staff, none of who could speak English, to make that dish possible), the President was treated to a lively medley of tunes, with one singer belting out the immortal Awara Hoon, only an 'l' replacing the 'r' in Mukesh's memorable rendition.

For all Bo's talk about Dalian being off limits to outsiders, the hotel bar, with Western rock music playing over its sound system, later that night had its share of attractive Chinese women willing to do more than just flirt with guests.

In China at that time, it was an offence for a foreigner to be found alone with a Chinese lady in a hotel room. One foreign guest, we heard the next morning, decided to take the chance, but balked at the door to his hotel room when he discovered that the price was not right, much higher than what he was used to back home!

Dalian was the only city on that Presidential visit where the Indian media bus was accompanied by police outriders and a police convoy. It was not as if its streets were packed with traffic. But its mayor liked impressing his guests.

Bo Xilai liked drama.

Please click Next to read further about the fall of Bo Xilai, a case like none other in contemporary China

Bo, the Rockstar

Six years later, in March 2006, Bo arrived in Mumbai to attend the inauguration of the Asia Society's centre in the city, accompanied by a large Chinese business delegation.

He was no longer the mayor of a city -- now matter how impressive -- but his country's powerful commerce minister.

Playing the great charmer with folks like Montek Singh Ahluwalia, then as now, deputy chairman of India's planning commission; and Singapore's brilliant Tharman Shanmugaratnam, then the education minister and now his nation's deputy prime minister and finance minister, Bo acknowledged with an imperial nod the obsequious bows of his compatriots as he swished around the ballroom.

His charm could be switched on and off like an electric switch.

As his counterparts -- like the European Union's smooth Peter Mandelson discovered -- dealing with Bo was tough business. Bo had decided that Nationalism would be his calling card and reiterating China's commercial interests forcefully would be what he would do wherever he went.

Shanmugaratnam revealed how Bo had dispatched camera crews to Singapore to film for a month how that city-State operates. The footage was later screened on Dalian television at prime time every night thereafter, so that Dalian's citizens could learn how Singapore residents went about their lives and emulate them in every way.

Bo walked around like a rock star at the Grand Hyatt hotel during his visit, flanked by bodyguards as tall as he was. The toughs would not allow me to come close to unsmiling Bo, until I waved my album of Dalian photographs at him.

As he quickly glanced at images from another time, Bo relaxed just a wee bit, smiled, ("Dalian, eh?"), put his arm around me for a nano instant, but shook his head when I asked for an interview. "Not this time," he said.

He was clearly on a high. A little earlier, when challenged by Mary Kissel, then the editorial page editor at The Wall Street Asia about the lack of democracy in his country, Bo had let fly, his vehement assertion of Beijing's Way greeted by rapturous applause from the Chinese delegation.

Could China learn about democracy and the rule of law from India, Kissel had asked, provoking Bo to launch a denunciation of democracy, arguing it was more important for a nation to feed its people than give them meaningless rights.

"Bo has shown what we do," one Chinese delegate, who confessed to being shocked by the Mumbai slums on the way to the Grand Hyatt, said later.

Bo, I had thought then, was poised to take over the reins of power after President Hu Jintao and Premier Wen Jiabao exited in 2013 after their compulsory two terms in office.

But that was not to be.

Please click Next to read further about the fall of Bo Xilai, a case like none other in contemporary China

Bo, always on the look for the Big Chance

The Bo I encountered at Rashtrapati Bhavan that November was not the Grand Performer one had seen in Mumbai.

Even though he was a leading member of President Hu Jintao's delegation to India, Commerce Minister Bo Xilai was playing it low key, very careful not to steal the Leader's limelight in any way.

Hu, it was said even back then, did not care for Bo. The careful, understated, technocrat did not fancy flamboyant folk like Bo. Hu and Premier Wen Jiabao preferred politicians who did not rock the party's boat in any way.

Moreover, Bo was seen as somewhat of a protege of Hu's predecessor, Jiang Zemin whose attempts to influence Communist party politics Hu detested.

At President A P J Abdul Kalam's ceremonial banquet for Hu on November 21, 2006, Bo paced the Ashoka Hall for about 30 minutes, dictating a speech on his dictaphone, deflecting all attempts to engage him in conversation with an apologetic smile.

Neither Communist Party of India-Marxist General Secretary Prakash Karat or his supposed rival Sitaram Yechuri -- both astute students of Communist history -- appeared to recognize Bo as the only one at Rashtrapati Bhavan that evening, with a direct link to Mao Zedong and the founding of the People's Republic of China.

Bo's father Bo Yibo was among the handful of Communist leaders who stood besides Mao and Zhou Enlai on the ramparts at Tiananmen Square on October 1, 1949 when the PRC came into being.

Even though he was close to Mao and often went swimming with The Great Helmsman, the elder Bo was ruthlessly purged during China's Cultural Revolution like so many of his comrades including Deng Xiaoping and Xi Zhongxun, whose son Xi Jinping will succeed Hu Jintao as China's next leader (general secretary of the Communist Party and president) next March.

Both the younger Bo and the younger Xi were uprooted from their privileged homes in Zhongnanhai, the quiet and leafy Beijing suburb where Chinese leaders live, and banished to a life of hard manual labour in the countryside. Bo's mother, it was said, was beaten to death by the Red Guards.

Bo, one account published before his downfall alleged, had knocked his father down to the ground to prove his hardcore Communist credentials to the Red Guards who came to take Bo Yibo away.

The Cultural Revolution left behind wounds that are yet to heal more than 40 years later even though leaders like Deng, the elder Bo and the elder Xi were all rehabilitated after Mao's death, and lived well into their nineties to see their version of Communism triumph.

Please click Next to read further about the fall of Bo Xilai, a case like none other in contemporary China

Bo wanted a return to Maoist values

Hu Jintao had wanted the transfer of power to Xi Jinping and Li Keqiang, who will succeed Wen Jiabao as China's premier, to be like his seven years in office -- minus any drama.

Even though Hu and Wen were not keen on elevating Bo Xilai -- who had moved to head the Communist party in Chongqing after his stint as commerce minister ended -- to the Chinese Communist Party politburo's powerful standing committee, which effectively rules the People's Republic, the ascension was seen as a possibility.

Bo's candidature was said to be backed by the ailing Ziang Jemin, who though supposedly at the gates of the Communist Valhalla, still had enough influence to call in favours.

In Chongqing, Bo cultivated a gunslinger image, cracking down on the city's gangsters, the triads, with unexpected vehemence and venomousness, winning much public applause for his tough stand on crime. His economic policies for the province emphasised the public sector, rather than private enterprise.

What perhaps unnerved China's technocrat rulers most was how Bo's unexpected championing of Maoist dogma -- calling for a return of Maoist values to China, accompanied by scenes of choreographed song and dance reminiscent of the Cultural Revolution -- apparently struck a chord with sections of the Communist Party leadership and the People's Liberation Army.

Both Hu and Wen kept away from Chongqing throughout Bo's tenure, never visiting the city once, clearly indicating how they felt about him.

Still, Bo, who has powerful allies in the Communist Party and the PLA, may have made it to his cherished spot on the politburo's standing committee had it not been for an Englishman named Neil Heywood.

Please click Next to read further about the fall of Bo Xilai, a case like none other in contemporary China

Did his wife bring Bo down?

Bo Xilai's life and career began to unravel at dizzy speed after his trusted police chief Wang Lijun, who had led his war on the triads in Chongqing, turned up at the United States consulate in Chengdu, 200 miles away, on February 6, seeking asylum.

Wang had turned against his mentor, reportedly bringing with him, a dossier filled with incriminating evidence against Bo and his family, information destined to end the princeling's political career, perhaps even send him to prison for a long time.

Consular officials, US diplomats at the embassy in Beijing and the State Department in Washington, DC went back and forth for the best part of a day, arguing the merits and demerits of granting Wang sanctuary and incensing Chinese leaders.

Finally, a deal was struck with officials in Beijing eager to hear Wang's story. Wang would be spirited out of the US consulate in Chengdu, protected from Bo's anger, and taken to the Chinese capital.

No one knows what has become of Wang -- it is perhaps best that way; Bo Xilai has powerful friends still in Beijing -- but his dossier led investigators to Neil Heywood's mysterious death.

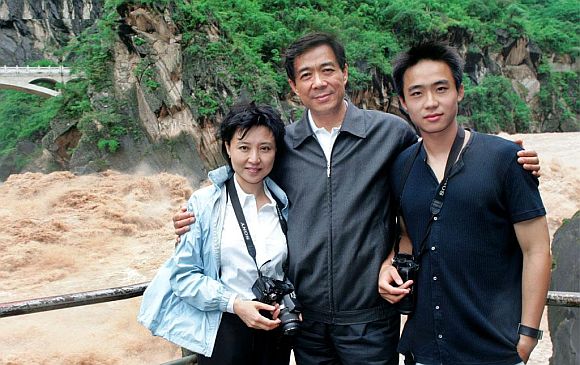

Heywood, a pucca upper class Englishman educated at Harrow, the public school which boasts of Jawaharlal Nehru among its famous alumni, first encountered Bo as mayor of Dalian. The two men reportedly got on famously as did Bo's attractive second wife, Gu Kailai.

Heywood is alleged to have profited from his association with one of China's most powerful men, directing likely businesses first to Dalian and later to Chongqing. For many years, all was hunky dory. No one knows when the plot got murky.

Did the 53-year-old Gu and the 41-year-old charming Englishman have a doomed romantic relationship? Did their trade ties go suddenly sour?

Each day, fresh details are leaked out of Beijing, each leak painting a fresh scene onto an already tawdry tableau. Whether it is the truth is hard to say, because the men or women leaking the information are obviously playing for high stakes.

They want to ensure that not only is Bo finished politically forever, but that his supporters in the Communist Party and the People's Liberation Army stay quiet because continued association with someone accused of covering up a murder would be too high a price to pay.

After Wen sacked Bo as Chongqing's party secretary on March 14 (he lost all his party posts last week after Gu was charged), there were rumours of a coup in Beijing for days thereafter.

There was talk of gun fire heard, of military vehicles sighted on important Beijing avenues, of hectic government activity.

So strong were the rumours that one Indian diplomat, with a passionate interest in China, called up the Indian embassy in Beijing and asked junior diplomats and officers to go out into the streets and report on what they saw. That drill reported nothing of consequence; it was business as usual in Beijing.

Still, the diplomat, who has years of dealing with China's foreign ministry and studying the political tea leaves in the Middle Kingdom, was not sure 11 days after Bo's ouster as Chongqing party boss how the drama would eventually end.

"The first shots have been fired in a long battle," was his assessment then.

The very next day, March 26, a report on Neil Heywood's mysterious death appeared in The Wall Street Journal. It was the first time that many of us had heard about the Englishman who was found dead last November.

The cause: Death by overdrinking. Only, as it turned out, Heywood, his family insisted, was a teetotaler. He did not touch alcohol.

Last week, Bo Xilai's wife Gu Kailai and a family retainer at Bo's home were charged with Heywood's murder.

One version alleges they served Heywood a drink spiked with cyanide. Bo is said to have discovered later about what transpired. Initially, he is reported to have promised Wang Lijun that the policeman could investigate Gu, but later backtracked and viciously turned against his protege.

China's leadership currently appears united about the action against Bo -- he is a political pariah now, removed from all Communist party posts, and reportedly under house arrest.

There has even been talk that Bo could face a firing squad for condoning a crime. That fate appears far-fetched. The days of executing someone as powerful as Bo are long gone in China, and the risks of inciting his support base -- among the public and in the corridors of power -- too great to ignore.

Bo Xilai, like other Chinese leaders who have fallen from grace like Zhao Ziyang, his enemies hope, will spend the rest of his days in political Siberia, kept away from a fawning public and away from view.

Unlike Zhao, who disappeared after Deng Xiaoping sacked him as general secretary weeks before the Tienanmen Square massacre in 1989, Bo is ambitious and young (he is only 62).

I doubt if Bo Xilai -- no matter what his wife's alleged crime -- will fade away quietly into the night.