Ajit Sahi in Cairo

Two Indian journalists find themselves in the midst of action the moment they stepped foot in revolution-hit Cairo. They share their experiences.

So the Revolution in Egypt is spreading. The symbolic nucleus is still at Tahrir (Liberation) Square in the heart of Egypt's capital city, Cairo, the roundabout and its expansive adjoining open areas where for the 20th consecutive day today, February 13, 2011, thousands continued to camp even though Hosni Mubarak resigned as president two days ago.

Now, the streets of Cairo have gone up in arms. The demonstrations, strikes and sit-ins have turned to the issues of social justice, employment, meaningful wages. And you know what? The insurance workers, weather forecasters and even the police started protesting today!

"I am in the police force for 20 years and still my salary is 400 pounds (Rs 3,200) a month," Tarik, agitated, angry, still serving in the police, told me as both he and I stood dangerously on a high wall opposite Mubarak's dreaded interior ministry, which controls the police.

As is now legend, Egypt's bloodthirsty police force brutalised the people of Egypt for more than two decades to maintain Mubarak's tyrannical dictatorship. In the early days of the revolution, the people took out their anger on the police that attacked had them, by burning down police stations across Cairo and by torching their vehicles.

"See around you," Sameer Abbas, a tour operator, had said to me as he drove us around the periphery of Tahrir Square on February 6, trying to find a way to smuggle us in with our ubiquitous news camera. "Only government buildings were set on fire. Only police cars were set on fire."

...

Video: Egytians protesting for a salary hike

'We want money. Want hospital'

Today, on February 13, more than a thousand policemen stood below us, many of them in their uniforms: black sweater, trousers, cap. These were unbelievable scenes.

Raju, my cameraman from UNI TV, and I had gone inside the frenzied protestors moments after the protest began. This is what they were saying: Bring out our officers from the interior ministry. They have no business to be there. We want a total overhaul of the police forces. We want better wages. Tarik said: "Want money. Want hospital."

Just behind them stood two tanks (the video in previous slide), with soldiers standing on them. An army officer jumped up the tank and, using a megaphone, tried to speak to the protesting policemen.

"No, no, no, no," went up the roar in Arabic.

...

Video: Award-winning New York Times journalist Thomas Friedman on Egypt's revolution

'I lied to the immigration about where we would be going'

Image: An Egyptian soldier atop a tank watches opposition supporters during a huge rallyPhotographs: Yannis Behrakis/Reuters

He could read from his paper till kingdom come, but these policemen-turned-agitators weren't going to go anywhere. The army men got really worried. Shortly, five of them came walking towards us and gently but firmly told us to leave.

What a change this has been in the behaviour of the police in just ten days!

On February 4, Raju and I landed at Cairo airport from New Delhi. After a three-hour wait at the airport, we took a taxi at 7 am, when curfew ended, to go to Hilton Hotel, where we weren't booked, but where I lied to the immigration we would be going.

Immediately, we began to seek tanks on the streets. By the time we reached Mubarak's Presidential Palace some three kilometres later, we had counted at least 12 tanks. It was scary.

A furtive look inside the Palace's compound gave us a glimpse of at least three tanks.

Immediately afterwards, the neighbourhoods began. And immediately, we were stopped by a bunch of young men, some still boys, wielding big machetes and butcher's knives, gesticulating wildly, angrily, asking us to get out.

'Everywhere, we had to open our luggage and show our camera equipment'

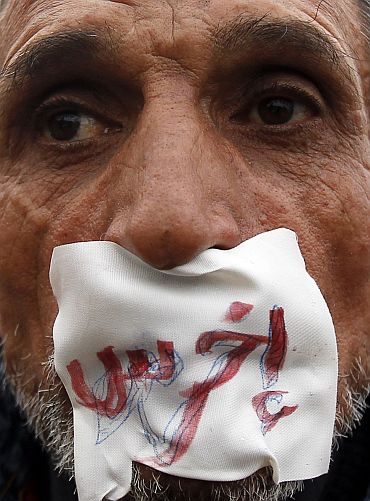

Image: An anti-government demonstrator looks on with a sign reading 'shut up' over his mouthPhotographs: Amr Abdallah Dalsh/Reuters

This was the second Friday after the January 25 protests began.

This was the day that the uprising at Tahrir Square had announced that they would bring a million people there.

This was to be the day of departure, for Mubarak. Hungry, tired -- having not slept on the nightly flight from New Delhi -- Raju and I stepped out of the taxi, opened our luggage and waved our passports. The kids were assuaged. We were allowed to move on.

But they were only the first of about six checkpoints we were made to stop at, the youngsters all dangerously armed, all speaking angrily and loudly -- only in Arabic, no one in English -- and everywhere, we had to open our luggage and show our camera equipment.

These were neighbourhood watch units that had sprung up all over the city overnight, with varying degrees of support or neutrality towards the revolution, but certainly not in favour of Mubarak.

By this time, I was getting the hang of how to deal with them, and I felt a bit better at it. Shortly, that would be my undoing.

'They were angry with us because we were journalists'

Image: A rock flies past an opposition supporter during rioting against pro-Mubarak demonstratorsPhotographs: Goran Tomasevic/Reuters

"Sahafi (Arabic for journalist)," I said loudly but pleasantly, half-grinning, at the seventh checkpoint. Within minutes, Raju and I had been forced out of the cab with our luggage and pay the cabbie the full fare of 100 Egyptian pounds (Rs 800), who quickly sped away. It was still only 7.30 am, we hadn't entered the city interiors. We were miles away from Tahrir Square.

These were pro-Mubarak people. They were angry with us because we were journalists. They were very angry, because they found on us equipment that we had brought so we could broadcast live from the Square, but which looked suspiciously like something that can be used to sabotage, and hardly at all like broadcast equipment.

And presently, the police were called. Our hearts sank.

"Come with us," a burly policeman in plainclothes grabbed our shoulders and started to walk us inside a lane, off the main road.

A group of men started following us -- some ahead, and some behind. Raju got separated from me. Of course, they already had our passports. Now, they had our luggage. We walked a half a kilometer, but it felt heavy to walk. I was nervous. And I was very nervous for Raju, who someone tried to slap around.

From one police station to another

Image: A pro-government demonstrator reactsPhotographs: Suhaib Salem/Reuters

As we reached a police station deep inside the alley, a crowd of about a hundred had gathered. We were marched inside the building and made to sit in one corner. Two feet to our left was a lock-up, grabbing whose bars stood some men pleading to be let out. I was convinced we were going to be arrested and jailed.

Our passport details were taken down. The men confabulated in Arabic among themselves.

When I tried to get up from the stone bench we were made to sit on, I was forced to sit down. When the officer asked someone for a pen, I handed him mine, and used that opportunity to not sit down again.

Then we were pushed in a car without our luggage (which we later found was brought in another car) and taken to another police station.

This next police station was a huge building. Opposite it, we noticed later, was the Egyptian Museum of Islamic Art. This was the crucial day of what everyone feared would be a second round of confrontation between the authorities and the protestors.

Already, the fire of rebellion had spread in other cities of Egypt outside Cairo, including Suez, where the waterway, the canal, joins the Red Sea of the Gulf of Aden with the Mediterranean Sea.

'We were made to sit in the car like thieves'

Image: Police officers stand guard in CairoPhotographs: Amr Abdallah Dalsh/Reuters

When we reached this building, we were now handed to a third set of policemen, and the second set, who had accompanied us from the previous place, vanished. The scene before us was remarkable.

We were made to sit in the car like thieves, on the back seat, Raju and I, keeping very quiet. Just below the open stairs of the police station, we saw about a hundred policemen in riot gear, their shields and crash helmets, being instructed by a huge officer speaking animatedly in Arabic, no doubt exhorting them to go beat the hell out of the protestors.

Outside the gate, a pick-up truck had been stopped previously. In its back sat about four men, conservative from their appearance as they wore the Islamic skullcap and the pointy beards.

They were quiet.

On the ground, the scene was more drastic. Just below the truck's back sat four men, all wearing the same skullcaps and beards, their hands tied firmly behind them, blindfolded. Raju and I continued to sit very still.

'Why are you carrying this book?'

Image: A police officer in plainclothes points his weapon at protesters while guarding a police stationPhotographs: Amr Abdallah Dalsh/Reuters

From the window of the car we saw our suitcases emptied out. One police officer found a book I had foolishly brought with me: The Israel Lobby, by two American professors, Chicago's John Mearsheimer, and Stephen Walt of Harvard.

He came to me and asked chillingly, "Why are you carrying this book?" Then we were asked to step out of the car. A few very young policemen -- possibly around 20 years -- were asked to guard us. We were now joined by a French journalist.

We were made to sit on a small curb. One of the policemen asked me, "Where you from?" I said, "India. Hindi. Al-Hind."

He beamed: "Ah! Hind!" And he began singing gibberish and dancing like Amitabh Bachchan danced in the blockbuster Laawaris when he sang Mere angne mein tumhara kya kaam hai. Somehow, it didn't lighten me up.

To cut a long story short. It did not get any worse from here. I plucked the courage to casually walk up to the police officer and asked him if he was going to detain us or arrest us. He drove away for a few minutes, then suddenly re-emerged, and asked all three of us, including the French journalist, to jump into his car.

Some of the young policemen objected that he was taking away their game. But he took us in the car, as his partner began speeding away.

'Don't go to Hilton, go to the Marriot instead'

Image: The Marriot hotel in CairoThis guy, a policeman, turned out to be an angel. "I am going to take you to a safe area," he turned back and told us. "Don't go to Tahrir today. Just go to the hotel."

He asked me where I was headed. I lied: the Hilton. He said, don't go there, go to the Marriot instead. The previous day, and even that day, pro-Mubarak elements had attacked journalists staying at the Hilton. At several checkpoints the police officer argued with those manning them and finally got us out to the safer, upscale neighbourhood of Zamalik, where most diplomatic staff stay.

"Thank you," I said to him from the bottom of my heart even as he stopped a taxi and shoved our stuff into it. "Go," he said to me firmly. "Go right away and don't stop anywhere."

'The police and the people are one hand'

Image: An Egyptian policeman is hugged by an opposition supporter in Tahrir SquarePhotographs: Suhaib Salem/Reuters

I am quite sure now that just as Egypt has changed forever with this revolution, so have its police force.

This was fully evident today (February 13) from the protests outside the interior ministry.

There were many non-police civilians, too, at this protest, and they often shouted together: "The police and the people are one hand."

This is a smart variant of the slogan the people began to raise soon as the army's tanks and soldiers had moved in around the Tahrir Square just a few days into the Revolution: "The people and the army are one hand."

What is most unique about this revolution is that the people have realised that they are up against all kinds and forms of establishment, and they want to have as many Egyptian citizens on their side.

The police are from among them, citizens first, and now that the great dictator is gone, and now that the nature of Egypt's ruling regime is never going to be autocratic and brutal as it has been until now, there is no doubt that the police will be far more accountable hereon than they have ever been.

This would be a very good thing. But for the new rulers of Egypt, the self-styled 'High Council' of the armed forces, this would be a headache, as more and more staff of the government begin to acquire the characteristics of a trade or workers union.

This was evident just a couple streets from the police protests at the interior ministry.

Now, the police themselves are protesting

Image: The sun sets on protesters as they continue to demonstratePhotographs: Dylan Martinez/Reuters

Sunday, was the first working day of the new week. (Egypt, as in much of the Muslim world, holidays on Friday.)

As the working hours began, about a hundred men and women gathered outside the office of the government-owned Masr Insurance Company, placards in hand, angry, protesting, well outside the confines of Tahrir Square.

What do you want? I asked them. "Our officers get thousands of pounds every month as salary while we get less than 500," Amar Muhammad, a clerk with the company, said. "We will not allow privatisation of our company as the government is trying to do."

People in India are used to street protests. But this is unbelievably unique in Egypt.

Ever since Hosni Mubarak placed Egypt under a state of emergency in 1981, around the time he seized power in the country, the people have never been allowed to even stand on the streets together in a group larger than six. It would invite arrest by the police.

Now, the police themselves are protesting.

'Egyptians have immediately become custodians of their nation'

Image: A man cleans the base of the statue of Egyptian Army General Abdul Moneim Riyad at Tahrir SquarePhotographs: Mohamed Abd El-Ghany/Reuters

This new Egypt may seem like a bit getting out of hand. But only those who are around here can understand that the outpouring -- without any leadership, still -- is totally within the control of the people.

It is incredible how the people have exercised this power with amazing self-restraint until now. The heady victory of the 18-day revolution could have driven the people crazy enough to damage public property.

On the contrary, they have immediately become custodians of their public spaces, their society, their nation.

All night and day and night and again in the day today, the Egyptian people -- volunteers with no leaders -- have been cleaning the streets of Cairo. It is amazing how much of Tahrir Square they have cleaned up.

'I don't trust the army'

Image: People walk past slogans near Tahrir SquarePhotographs: Asmaa Waguih/Reuters

But there is one cause for alarm. Last night (February 12-13), about six young revolutionaries went missing from the Tahrir Square.

I spoke to a few eyewitnesses, who said the army soldiers came in a day before in the afternoon and that night, and picked them up, forcing these protestors to go with them.

"We haven't heard from them since," one of their comrades at Tahrir told me, very worried. "Their mobile phones are switched off."

Shortly afterwards I spoke to a lawyer named Yasir, who are among the thousands that continue to camp at Tahrir. "I don't trust the army," he said bluntly. "That is why we aren't going from here until a full transfer has been made to a civilian government."

article