| « Back to article | Print this article |

Exclusive: 'Headley said had contacts in the drug mafia'

'The bond between Rahul and David was a powerful one. While Rahul saw a father figure in Headley, the latter saw Rahul only as a codename for Mumbai.'

'Rahul had spent approximately 1,000 hours with Headley and planned to spend more, when Headley was finally busted in the US.'

'Rahul was devastated. He had lost a father figure for the second time in his life.'

Exclusive excerpts from S Hussain Zaidi's latest book, Headley and I.

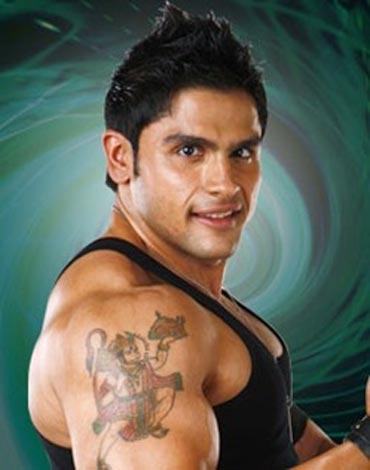

Over to Rahul Bhatt, the narrator:

No one spoke for a long time, and I felt myself being assessed by the interrogators. I looked at the nameplates on the uniforms of the officers and memorised their names. There was Deputy Superintendent Rajmohan from the Kerala cadre of the Indian Police Service -- he was from the NIA (National Investigation Agency).

There was an IB officer named Radhakrishnan. The third man in the room was an officer of the rank of inspector general, who was introduced to me only as Singh. He looked extremely fit, a rarity among our law enforcers. He had a tiger moustache and sat straight-backed and stiff. He was clearly the man in charge.

Singh started to speak. He began by telling me about himself, probably to put me at ease. He said he was an IPS officer from the 1986 batch, and that he too was a fitness freak like me. "Do you know, Rahul, I'm a marathon runner, and I run five kilometres every day," he told me conversationally, as if we were two participants in a fitness programme.

"That's impressive, sir," I replied.

The interrogation that followed was pretty much the same as the one conducted by (Then Mumbai Joint Commissioner of Police, Crime Rakesh ) Maria. The same questions -- how I had met David (Headley), where I'd met him, how long I'd known him, where I'd taken him, what we did and so on.

By then, I had gone over everything so many times in my mind that I had no difficulty in answering any of the questions.

I spoke for about thirty minutes, and they kept firing questions at me continuously about Headley and my association with him. Singh never interrupted me when I was replying, asking the next question only after I had finished answering the previous one.

He was a good listener, and kept taking notes as I spoke. Soon, though, he started asking me some very weird questions.

"Rahul, do you speak Arabic?" he asked.

Arabic? Me? I told him that not only did I not speak Arabic, I knew nothing about the language.

The next question was equally intriguing. "Have you ever been to Pakistan, Rahul?"

I was flummoxed. I was a hundred per cent sure that these guys had access to my passport and visa status. All they had to do was refer to their notes and they would know. Nevertheless, I told Singh that I had never been to Pakistan.

It dawned on me that the four men were playing some kind of mind game with me. I noticed that while Singh was doing the actual questioning, Radhakrishnan was watching my reactions like a hawk.

I realised later that he was probably working out some sort of a psychological profile based on my responses. I thought of Vilas (Varak, personal trainer and Rahul Bhatt's friend, who also knew Headley)down there at the reception, awaiting the same fate as I was, facing such menacing men on his own. It was all a bit unsettling.

All of a sudden, Singh again changed the subject, and asked me for some tips on fitness and on a proper diet. How should he work out? What was my specialty?

I answered all his questions patiently, giving him some tips on nutrition and some exercises and weight training that he could do. Suddenly, while we were in the middle of fitness tips, Singh changed tracks again. "Mr Bhatt, are you hiding anything from me?"

"Because if you are, we will confront you with evidence and then you will have no defence left for yourself." He probably thought that I would be thrown by this, but I was expecting it and was ready. "No, sir, I'm not hiding anything at all. Everything I'm telling you is the truth," I said.

He steepled his fingers and looked hard at me. Then he said, "Okay, I can see that you want me to believe you. Then tell me something. If you're not hiding anything, why did you refer to him as Agent Headley?"

I had already answered all the questions about why I thought Headley was an American agent and probably from the CIA (America's Central Intelligence Agency). But since I was being asked again, I decided to tell him a little bit about myself.

So, for the next few minutes, I told him about my interest in crime, that I loved reading mysteries and books on crime and weapons, and that I found security networks fascinating.

I told him that as I kept reading up on all this, I started looking at everyone around me a little more suspiciously than usual.

When Headley began to tell me about his past life, my suspicions grew. Headley always liked to flaunt his knowledge about spy craft and espionage, and his knowledge of different kinds of weapons.

He once told me that he had spent time training with the Special Security Group of Pakistan. He knew how to operate different kinds of weapons, like the Austrian Steyr AUG, the Chinese Star pistol, the AKM, and the Heckler & Koch German

rifle.

He had trained to use the M-16 rifle, as well as the Glock pistol. In fact, he said he had also been trained to use an RPG, an anti-tank grenade launcher.

"So, Mr Singh, when someone tells you all these things, what do you make of it?" I said.

"He told me he was just a businessman who has an immigration office. But how does a simple businessman come by all this knowledge? And what the hell is a businessman doing getting training in so many different kinds of weapons?"

I was in full form, unloading all the information stuffed in my head. My only thought was to somehow convince these men in the room that there were a million things about David Headley that, in retrospect, didn't add up and which would lead any logical, rational man to believe that he was much more than he seemed, perhaps even a sophisticated agent.

I told Singh that Headley had once told me that he knew Ayub Afridi. "I had never heard of this man at all!" I said. "But Headley told me that Ayub Afridi was a hot-shot drug lord, the Pablo Escobar of Pakistan. And he told me that he knew him personally. What else would you make of him, Mr Singh?"

I paused for breath, and wondered if I should go on. Singh gestured to me to continue.

I told them about the weapons bazaar that Headley had once spoken about. He had said, while talking about Afridi, that there was such a bazaar in Peshawar, Pakistan, where one could get Uzi submachine guns cloned in Iran. Imagine!

Not only did the man know what Iran was making and that such guns were being cloned, he even knew where they were making them and where they were being sold.

Headley also told me that heroin was openly sold in Pakistan and that he had some very good contacts in the drug mafia there. According to him, the entire drug belt in the Pashtun area of Pakistan was run by the heroin mafia. He once told me an anecdote about the manufacture of heroin there, which I thought I would share with Singh.

According to Headley, one of the sure-shot and most commonly adopted ways of manufacturing heroin undetected was to do it in a moving vehicle.

If the vehicle is constantly on the move, it's virtually impossible to track it. So, they would carry out the entire process in a moving Toyota station wagon.

The workers would climb in with all the raw materials, and the vehicle would start moving towards the drop-off point for the drugs.

Along the way, the raw materials would be processed and converted into the heroin that was sold internationally. Headley said that all this was being done openly in Pakistan.

Excerpted from Headley and I, by S Hussain Zaidi with Rahul Bhatt, published by HarperCollins India, with the publisher's kind permission.

Please click NEXT to read further...

'Headley was a handsome version of Steven Seagal'

Over to Rahul Bhatt:

My meeting with David Coleman Headley at Shivaji Mandir (a theatre which stages Marathi plays in Dadar, central Mumbai)is a blur in my mind.

Vilas (Varak) had called me earlier in the day and told me that he was bringing a friend to an event we were to attend that evening. He asked me if I would buy tickets for them, as they were running a little late.

I had the tickets ready and was waiting for them with my friends when they arrived. Vilas introduced David and me, and told me that they had met at the gym where Vilas worked as an instructor.

The first thing that struck me was David's eyes: One was brown and one green. I had never met anyone with mismatched eyes before. I later found out that it wasn't as uncommon as I'd thought it to be.

In fact, some famous people like David Bowie, Kiefer Sutherland and Christopher Walken have a similar condition, which is known in medical terminology as heterochromia iridum, where one iris is a different colour from the other.

It is often a genetic abnormality. But seeing David, how could I have known at the time that the man had two very different kinds of genes in him, with a Pakistani-Punjabi father and an American mother?

When Vilas introduced us, David said, "Hey, what's up?"

He had a friendly voice, and as he spoke, he stuck his hand out. We shook hands, and I was impressed by his strong, confident grip. David was wearing dark glasses, which he took off later, a cap and a grey T-shirt and jeans. He was holding a digital camera in his left hand, which I assumed he was using to take pictures of Mumbai, like any other tourist.

I thought David looked familiar, and then I realised why. He looked like a more handsome version of Steven Seagal, the Hollywood actor.'

Excerpted from Headley and I, by S Hussain Zaidi with Rahul Bhatt, published by HarperCollins India, with the publisher's kind permission.