| « Back to article | Print this article |

The Return of India's Lost State

The biggest change in Bihar, discovers Archana Masih, is the distinct feeling of optimism -- that something good is finally happening in the state.

In the bustle of the festive season in Hathua Market, the garment bazaar in Chhapra in north Bihar, an aspiring MLA gets a kurta-pyjama stitched in three hours to make the deadline for filing his nomination for the assembly election.

Outside the town's collectorate, half the road is barricaded to prevent aspirants arriving with large crowds of sloganeering supporters.

Central Industrial Security Force personnel are stationed near government administrative buildings. On the road from Patna to Chhapra, police search passing cars.

When the constituency goes to the polls on Thursday, October 28, security will be so tight that shops, schools, offices will remain shut; private vehicles will be off the road; people will walk to the polling booth; the town's borders will be sealed.

'If Nitish is not voted back there'll be no one left to save Bihar'

"In my lifetime, this is the first true election of a democracy," says Vijay Gupta, who runs a school in Patna and has a razor-sharp interest in politics. "If people do not vote for Vikas Purush Nitish Kumar, there will be no one left to save Bihar."

After over 15 years of deplorable neglect, some change has finally come under the present Janata Dal United-Bharatiya Janata Party government which is seeking another term in power.

There is a long way ahead, but Bihar seems to have set course.

Once India's most well governed states, the pinnacle of its ancient past from where the national emblem, the Ashok Chakra, draws its origin -- Bihar had sunk to being one of the most underdeveloped, most lawless in the country and remains India's most illiterate state.

'I would start receiving calls if I wasn't home early'

Earlier, 7 pm was a deadline of sorts.

"That clearly is the biggest change impacting ordinary life and businesses, people are not scared to roam in big cars or to invest," says Gaurav Singh, a young management professional who left his job at a multinational financial firm in Mumbai to return to Patna a few years ago.

With the bustle in the market, a return to the cinemas and restaurants, girls driving back from coaching classes in the night, even lovers chatting on parked motorbikes on the road to the Gandhi Setu -- law and order has improved in the capital and also in other parts of the state.

'Fear has receded'

"There was a time when Dabbang-neta types would enter the shop and you would feel nervous. Now it is not so."

"A few years ago wholesalers from other states would hardly send their agents with samples of saris neither would they give us goods on credit," adds the businessman whose family has been in the cloth trade over two generations. "Now not less than 15, 20 agents come in a month and getting credit is no longer a problem."

A change from the time when kidnapping was an industry

Though the statistics for theft, dacoity, rape, atrocities against women may not be encouraging, the mood is different compared to those days when kidnapping was termed an industry in Bihar.

The soldiers who did not return from the War

Dedicated to the men who fought in World War I, two of whom did not return, the stone tablet with elegant lettering is still pristine white in spite of the daily dust clouds from the roads.

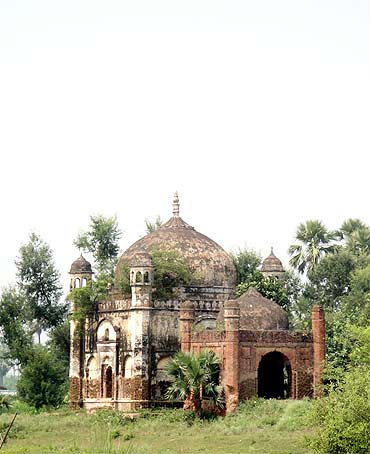

Down the road in Karinga village, the flat green landscape is broken by the ruins of a beautiful Mughal-style domed entrance to a Dutch cemetery where the Dutch chief of Bihar was buried in 1712.

The Dutch established their trade in saltpeter in Chhapra by 1664 and had held possession before the English arrived.

The Dutch were also here

"You didn't see these big foreign road-building machines on village roads before," said Liaquat Ansari, who has driven on these roads for many years now.

Under the stewardship of Secretary, Roads, Pratyaya Amrit -- a young bureaucrat who turned around the Bihar Bridge Development Corporation from the verge of liquidation to 'one of the the highest tax payers in eastern India' -- huge expansion and repair of the state's roads was undertaken, both in the cities and rural areas.

Opportunities in the private sector have still to emerge

"But I was pleasantly surprised that the roads in Bihar were as good or as bad."

Patna residents take pride in mentioning the flyovers that have been built, the roads that have been widened, the three malls that are coming up, new parks, the private banks and scores of cellular companies that have set shop.

Going by the billboards dotting the city landscape, mobile networks are the biggest advertisers.

But although telecom, financial and insurance services are growing significantly, mass employment opportunities in the private sector have still to emerge and the setting up of new industries is yet to occur.

Typical aspiration of Patna's youth: Work for an MNC

With multinationals like Max New York, Uninor etc entering the state, the typical aspiration of the city's youth is to work for an MNC adds Singh who explains that the issue is not the availability of jobs as much as the availability of the right kind of candidates to fill those spots.

"HDFC, Stanchart have positions, but are not getting people with the right skills," he says, "because I don't think there are enough good management graduates in the city."

'Bihar's per capita income is 1/3 of India'

A proposal to revive the famed Nalanda University has also been cleared by the central government.

However the state's universities, that are centres for imparting mass education, remain in a dismal state.

The state government has acquired land to develop a knowledge hub in Bihta near Patna and city professionals are hopeful that it will boost the higher education infrastructure in Bihar.

"Bihar's per capita income is 1/3 of India," says Gaurav Singh, "But the platform has been laid, the real work lies ahead."

A factory town that died, may live again

The little town in Saran district also has the now defunct British-initiated Morton chocolate factory.

Three factories that had been the mainstay of employment in the town have been shut for decades.

Marhowrah may finally see industrial action soon.

Timed with United States President Barack Obama's visit to India next week, newspaper reports say an American company has been shortlisted to build a diesel engine manufacturing factory in partnership with the Indian Railways.

'It's a wrong impression to think that industry is directly related to development'

"You need private investment which will only come when you have the advantage of infrastructure."

"Building infrastructure is expensive and does not give immediate return, so even though the state government has done work on improving roads, power is a serious problem and an extremely expensive proposition."

Like with Punjab and Haryana, Professor Ghosh feels the only way for Bihar to attract industry is by ensuring that its agricultural economy prospers abundantly so that people find it profitable to start industries in the state.

The state government's attempts towards becoming an ethanol hub came a cropper when the central government did not grant its approval to the state's sugar industry to produce ethanol to generate electricity.

Neither could Bihar get central government permission for coal linkages for its thermal projects.

"Of course, the central government was unkind to them on this," feels Professor Ghosh, "On the industry front much has not happened, but it does not matter. Many have this wrong impression that industry is directly related to development. How then did Punjab, Haryana, Western UP grow? Industries followed 20 years after agriculture development over there."

'We've got so used to power cuts that it is a shame!'

Since huge, perhaps unfeasible, investment is needed to produce electricity, experts feel the only way out is to have the ability to buy power for which it is necessary to curtail distribution losses and the theft of power.

"For us bijli aa gayi! (electricity has come!) makes news rather than bijli chali gayi (electricity has gone)," Shehzad, a young government employee in Chhapra had told me during the Lok Sabha election campaign in the state last year.

"We have got so used to it that it is a shame!"

'Women now go to the government hospital for deliveries'

A few years ago, the hospital had broken window panels, pealing paint and ragged facilities.

Tales abound of how patients died en route to Patna in private Maruti van-turned into alleged ambulances due to an almost non-existent government health infrastructure.

Though government medical facilities are nowhere up to the mark, residents discuss the increased patient numbers in the OPD (Out Patients Department) and the modern 108 ambulance service aided by the Centre, which sometimes makes as many as three trips from a town like Chhapra to Patna each day.

"Women prefer the government hospital for deliveries because they get money for diet and care from the state government. The lady doctor customers in my shop say their practice has taken a hit because the Sadar hospital has finally shown some improvement," laughs Rajesh Mishra, who owns a cloth shop in Chhapra.

"Most importantly," says Professor Prabhat Ghosh, "government hospitals have at least become functional."

'In the last 15, 20 years our Bihar had gone back 40 years'

To the critical eye, Chief Minister Nitish Kumar's five-year performance record, though praiseworthy, may seem exaggerated, but "it is not false, there is a difference between the two," feels Professor Ghosh.

One reason for this is because the average Bihari tends to make a comparison with the last decade where development had hit such rock bottom that not a single new school was built or any teacher hired.

"In the last 15, 20 years our Bihar had gone back 40 years and we can't make up that lost time in just five years," says Patna resident Vijay Gupta of a state where caste equations remains the most potent factor in every election.

"You cannot win an election without development and if Nitish's government doesn't come to power the main reason will be caste."

'If people like Nitish are not re-elected, I see no point in a democracy'

"An investment of Rs 1,000 crores (Rs 10 billion) in Gujarat can happen in 3, 4 days while in Bihar it is going to take some time," says Gaurav Singh, sipping black coffee in his office above a shopping complex in Patna.

"In five years you can't ask for everything and get everything," he adds. "We couldn't ask for more. If people like Nitish are not re-elected, I see no point in a democracy."