Rediff.com's Prasanna D Zore speaks to the survivors of the Bhopal gas tragedy, who recount their tales of horror after the court's verdict on June 7, after a tortuous 25-year fight for justice. The eight accused in the worst industrial disaster were given a two-year imprisonment and released after they paid a fine of Rs 25,000.

'Yes I am Shamshad Bi," says a voice from the other end of the phone that sounds like that of a teenager. "I will introduce you to a number of people who lost their wives, sons, mothers, daughters and in-laws... in the tragedy and can recount the horror of that night for you," she assures.

"You come to J P Nagar where there is a statue of a mother with her infant son in her arms as she weeps and tries to run (away from the poisonous MIC gas)," says the lady decribing the meeting point. You feel Shamshad Bi -- as she is fondly called by the denizens of this lower middle class mohalla that spreads across the road where Union Carbide India plant is located -- is a happy-go-lucky type, who perhaps was born much after the Bhopal gas tragedy and hence was so oblivious of the sorrows and pain of the people whom she had promised to introduce to this correspondent.

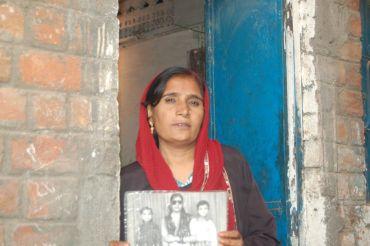

The surprise registers when you come across a 48-year-old lady who, clad in a burqa and red dupatta to cover her head, stands before you. She walks with a brisk pace as she introduces me to 40-year old Rehana Bi, 47-year old Mohammed Habeeb, 60-year old Tulsiram, 60-year old Jamunabai, 76-year old Mohammed Sabir, 57-year old Kusum Bai and 76 year old Ganesh Ram, all of whom survived not only the spread of the dreaded methyl isocyanate, that engulfed the city, but also the death of their kith and kin.

The surprise turns into shock when Kusum Bai tells that Shamshad Bi lost her two-year old son Raja and her mother-in-law on the night of December 2 and later her husband succumbed to lung cancer that he developed because of the gases that entered his bloodstream on that fateful night. "I am alive today only because I keep myself occupied with the sorrows of other people," she says when she is told that she doesnt look like a victim.

"Main hansti, khelti rehti hu isiliye zinda hoon" (*I try to smile and keep myself happy. That's one of the reasons why I am alive today)," says Shamshad Bi.

"My son and mother-in-law died the same night. I lost two people from my family but there are several others who lost more than 10 family members in just a few hours. I keep telling myself there are people who suffered bigger tragedies than I did and yet are carrying on with their lives. "Unka gham dekhkar apna gam bhool jaati hoon" (I see their sorrows and forget my own)," she says matter-of-factly.

The first household that we come across is Rehana Bi's. She was in her mid 20s and was five months pregnant when she heard a loud commotion outside her house on December 2, 1984. She was sleeping in the inner room along with three sons Hafiz, Hamid and Nadim while her mother-in-law was sleeping in the outer room that looked across the Union Carbide factory with just a narrow road in between.

Her husband was on duty that night at a private factory on the outskirts of Bhopal. "When we came out to see what the matter was, my eyes were burning, I felt some problem inhaling the noxious air. I covered my two-year old son Nadeem in a thick blanket and ran with the other two kids and my mother-in-law," she says recounting that fateful night. In between this conversation she whips out a photograph that shows herself, her mother-in-law and neighbour sitting beside each other, their eyes draped with a wet handkerchief.

"I don't remember how much we ran but when I opened my eyes two days later in a hospital I learnt that my foetus was aborted due to the gas," she says. Her mother-in-law died two years later because of the noxious MIC, Rehana Bi says. However, the tragedy still haunts this family. Only a fortnight ago, Rehana Bi was hospitalised for breathlessness and was put on a ventilator for two days. "This is a recurring problem with most people who survived," she informs about the common bouts of breathlessness and allergies that most of the people in J P Nagar suffer from.

Today, Rehana Bi's left hand is partially paralysed. She suffers from breathlessness even when she walks a few steps. The then state government put her in the 'B-medical' category case which made her eligible for a compensation of no more than Rs 25,000. However, she has an indomitable spirit. She wasn't heartbroken after the June 7 verdict that slapped a two-year imprisonment on the eight accused in the case under section 304 A and released all of them after they paid a fine of Rs 25,000.

"We are not fighting for a court's decision. We are fighting to seek justice from an unjust system, from a multi-billion dollar MNC. Our fight will continue," she says echoing the sentiment of all those Bhopalis who suffered immensely, not only because of the gas that leaked but also from the callous attitude of the state and central governments.

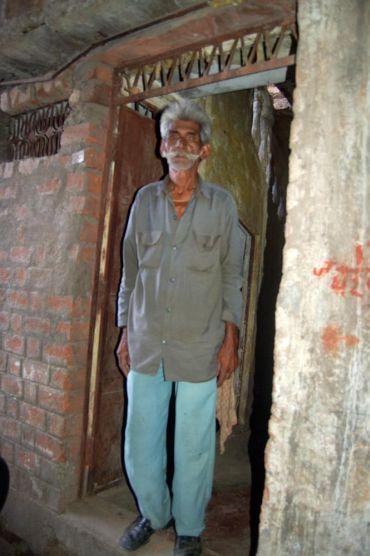

Mohammed Habeeb lives in a one-room shanty in the bylanes of J P Nagar. His employer sacked him after he found out that Habeeb's eyesight and his ability to do manual work had reduced after the gas tragedy. To make matters worse his elder brother was detected with lung cancer in 1987, an after-effect of the MIC inhalation, Habeeb informs.

"His operation in Bhopal was not successful. So we took him to the Tata Memorial Hospital in Mumbai," he says but there was no improvement and his brother died in in 1989, a few months before the Government of India agreed to a compensation of $ 480 million dollar from Union Carbide. Later he lost his mother who had damaged both her lungs over a period of six years after 1984. His daughter Rizwana, 24, suffers from lung infection and allergies.

Habeeb spent almost Rs 6 lakh on his elder brother's cancer treatment. He got the money from several NGOs working for the victims of Bhopal gas tragedy and the compensation he recived after the gas leak. "We can't treat Rizwana properly because we are broke now. We had one house which we sold to finance the treatment of my brother and mother. Hum log bhi sisak, sisak kar ek din dum tod denge" (We too will die a slow and painful death one day)," he says lifting his shirt to show the scars from a stomach operation that runs across the dorsal and front side of his torso.

Habeeb, no doubt, is pained by the June 7 verdict, "Aam aadmi ko dikhane ke liye leepapoti ki hai yeh" (the verdict is just a sham to silence the anger of the man in the street).