| « Back to article | Print this article |

Bahrain protests: Too many leaders, no leadership

The failure of the protests in Bahrain holds a few lessons for future democracy movements in Arab nations, claims David Moon.

Rarely is a senior United States official like Defence Secretary Robert Gate taken in by foreign enemy, let alone an ally, but that's exactly what occurred on March 12 during his talks with Bahrain's royal family.

Gates reportedly told King Hamadbin Isa Al Khalifa that tensions on the island should be eased and negotiations toward real reforms begun in earnest. Gates said he told Bahrain's rulers, "Baby steps probably would not be sufficient... real reform would be necessary."

Gates went on to say Bahrain's leaders were "between a rock and hard place."

Article courtesy: AFI Research

Bahrain sought Saudi's help to crush protests

Looking back, the "rock"-- instead of it being Iran as claimed by many -- was actually the reform-minded US.

The "hard" place was symbolised by the reactionary Saudis in Riyadh.

By March 14, it was clear that King Hamad decided to extricate himself from his dilemma by turning to the "hard place," signified by a force of 1,000 Saudi troops and 800 United Arab Emirates policemen that poured across the King Fahd Causeway.

Their mission was to take control of government buildings and commercial facilities, freeing Bahrain's police to concentrate on breaking up the mobs of Shias clustered around the country.

Police cracked down on protestors

Bahrain's police went on the offensive the next day. Shia protesters in and around Sitra, south-west of capital Manama, were attacked with tear gas and rubber bullets, resulting in heavy casualties and breaking up their temporary encampments.

The violent confrontation between police and protesters at Sitra may appear a side show.

The northern end of the island houses the nation's oil stocks -- a LNG plant and the terminal of a Saudi oil pipeline.

With the addition of a petrochemical plant that exports ammonia and methanol, jointly owned by Bahrain, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, these oil assets account for 60 per cent of Bahrain's governmental income.

Smack-down for US foreign policy

The security of this irreplaceable petrochemical complex was vital to Bahrain and Saudi Arabia's economic interests.

It was during this initial brawl between police and protesters that King Hamad declared a three-month state of emergency, throwing in a curfew between 8 pm and 4am.

Such a well-coordinated effort was planned days ahead, even as Gates visited King Hamad and Crown Prince Salman bin Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa.

With no apparent warning to Washington, the close and secret coordination between King Hamad, Riyadh and Abu Dubai was a smack-down for US policy interests.

Protestors rejected offer of talks

The attack at Sitra was the turning point that would soon witness the violent end to month-long massive protests, beginning with the deaths of four protesters at Pearl Square.

From here to the violent end, the protesters enjoyed US diplomatic support that served to restrain the government from more lethal assaults in and around Pearl Square.

Despite the assurance by the US against violent repression, political leaders leading the protests could not weld together a cohesive plan of action.

When the crown prince finally offered to hold an inclusive 'national dialogue', the secular Sunni party of Waad and the largest Shia group of al-Wefaq refused.

Royal double dealing?

These leaders have had a taste of royal double dealing when King Hamad ripped up the 2002 Constitution, making the elected parliament answerable to a new regime friendly Shura with absolute power.

Even so, instead of brandishing their non-violent credentials with negotiations, the mainstream parties called for a constitutional monarchy and the dismissal of the present government.

This was a critical mistake for the Shia group's credibility abroad. The offer by the regime to hold talks without preconditions was seen as the reasonable step forward.

US President Barack Obama and his administration continued to support the crown prince's call for dialogue.

Protests were violently crushed

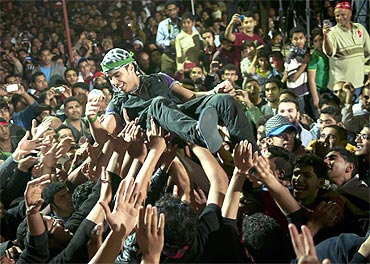

Protests of varying sizes -- with hundreds and thousands of agitators -- saw the parliament surrounded by a human chain, a march to the royal palace that was turned away, marches in the diplomatic quarter, a confrontation with Sunnis at the university and a group of Shias encamped in Bahrain's financial harbour.

On March 13, a few hundred of the more radicalised Shia youth tried to block access to the financial district across King Faisal Highway.

Bahraini police answered the challenge in an effective but violent manner, using rubber bullets and tear gas against the protestors.

The protests choking off the financial district tipped the balance for King Hamad.

On February 28, the crown prince claimed that the government was there to protect the 'interests of citizens', warning protestors against targeting the country's economic interests.

The largest moderate bloc in the Opposition, Wefaq, did not support protest marches to the financial harbour and the royal palace.

Divide between moderate and radical protestors

Both protests were thought to be too provocative and certain to illicit a negative response from the police.

The more provocative protests were mostly planned by Hassan Mushaima, a leader of al Haq, who slithered into Manama on February 26 from self-imposed exile in United Kingdom.

Welfaq and other moderates condemned these methods, but the Opposition was too fractured to forbid them.

Instead, al Haq became the hostile representative of thousands of peaceful protestors in Pearl Square. Msuhaima's combative manner paved the way for Saudi and UAE intervention, taking over what was once a successful and compelling non-violent protest.

The method of protest changed

In releasing extreme Shia leaders like Msuhaima from exile and Abdul Jalil al-Sangaece and others from prison, King Hamad opened his jails, an act affecting the final outcome on Bahrain's streets.

From Msuhaima's first appearance at Pearl Square on February 26 until his arrest, the method of protest went from effective civil disobedience to the risky stance of confrontation punctuated by calls for a Republic.

As long as the protesters peacefully occupied the Pearl Square, the masses enjoyed US support against police action after the confrontation with riot police on February 17 killed four protestors.

Once demonstrations in key economic and political areas became the norm, the king was less constrained by Washington's calls for non-violence and negotiations.

Lessons to be learnt from Bahrain protests

The failure of the protests in Bahrain should teach a few lessons to future movements for democracy in Arab nations.

Firstly, when the local power asks for negotiations, participate in them and make a media splash while doing so, even if there is nothing at that time to be gained at the table.

Secondly, build a cohesive leadership around moderate political leaders with governmental experience. Then choose a leader.

Thirdly, do not allow effective civil disobedience to be hijacked for the provocative designs of a few radicals.

The month-long protest by Bahrain's Shia community could have turned into an indefinite stand-off. In doing so, the protesters and their leadership would have mounted increasing pressure on the government for real reforms.

Instead, protesters were dislodged from Pearl Square when the time came. Msuhaima and al-Sangaece were arrested along with four other opposition leaders.

Perhaps these prisoners will have plenty of new stories to share with the Bahraini police.