| « Back to article | Print this article |

Astad and Delhi's street kids ready to woo CWG

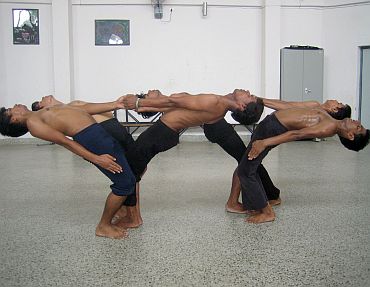

Fluid as a river, sometimes strikingly staccato, dance maestro Astad Deboo's students leave you speechless.

If there's anything more awe-inspiring than their performance, it's the fact they have been trained for not more than two years.

They belong to the Salaam Baalak Trust, a non-governmental organisation working for the street children of Delhi and Mumbai, and this is their last day of rehearsals before their performance at the Commonwealth Games on Monday.

"We're excited, but not too much. We're practicing like we would have for any other show," says Avinash, 19. "This way we remain focused on our art."

Control and discipline are the most striking aspects of their repertoire.

The lithe figures fold themselves into tiny molecules before presenting themselves as swords in the 60-minute piece titled Breaking Boundaries.

"This choreography attempts to explore the relationship between body and space," says Deboo, looking at the gravity-defying contortions of his boys.

Space is always the crucial element of a performance, he believes.

In this case, it is about finding your space and going beyond it in order to break the boundaries of your existence.

The dancers translate this idea through aerial jumps and diverse acrobats.

Please click on NEXT to read more...

'From Bollywood apes, Deboo turned us into mature dancers'

The music has been composed by Philip Tann interspersed with mandolin maestro U Srinivas and flautist Rakesh Chaurasiya's talent.

This requires a deep understanding of electronic and industrial genres of music.

And this was the greatest challenge for the 12 dancers.

"We have been used to dancing on Bollywood songs, which is different from Deboo sir's music," says Pankaj. "At first we had a very hard time grappling with the music, which was without consistent beats, but it's easier now. We count and pick up the cues."

The flawlessness of their repertoire is partly credited to the perfectionist master.

"He is very hard to please," says one dancer.

But they all agree that the mentorship of a celebrated dancer like Deboo deserves seriousness and dedication.

"He has gregariously modified our technique; we have turned into mature dancers from petty Bollywood apes," says Rohit.

Deboo's style exhibits the marriage between traditional and modern tenants of dance.

"I am a creator; I like to create my own vocabulary, which is popularly understood as a contemporary form," he says.

In the last sequence of Breaking Boundaries, he seems strongly rooted in the classical traditions. One who is proficient in his experiments with mudras and bhavs.

Deboo was schooled in Kathak and Kathakali and spent years at the Martha Graham Centre of Contemporary Dance, New York. He was awarded the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award in 1995 and the Padma Shri in 2007 for his contributions to contemporary Indian dance.

Between performing and teaching, he chooses the former. "I can never be a 24x7 instructor, but when I take up a project I invest everything in me," he says.

The fire in their bellies

Rekha, 13, the youngest in the group, is enrolled in an open school; Pankaj is a theatre artist; and Rohit is learning Chhau (an Indian folk dance).

They meet thrice a week for rehearsals, which commenced in August.

"We are here because of our passion. Most of us want to make dancing our career," says Neetu.

And this has made their journey more difficult.

"In our families, dance is considered a mode of entertainment; to amuse oneself occasionally," says Saleem.

"I can never explain my interests to my folks," he adds. "They can never feel the gravity of what we do here and that's tragic."

It was this sincerity that won them a platform like this, feels Deboo.

"I remember (Delhi Chief Minister) Sheela Dikshit walking up to me after watching the show in 2009, asking me to incorporate this into 'Delhi Celebrates', a cultural bonanza during the Commonwealth Games," he says.

"It was an honour," adds Deboo. "Perhaps she saw the fire in their bellies."