| « Back to article | Print this article |

In Memoriam: Homai Vyrawalla, India's first woman photographer

Pinned to the walls of a sprawling, charmingly-lit gallery in south Mumbai, frozen in black and white, are some of the most breathtaking moments of Indian history. The starkly clear, yet haunting, photographs document the social, cultural and political transition of a new-born nation trying to find its feet.

The 250-odd photographs represent the best work of Homai Vyrawalla, India's first woman photographer. As an employee of the Far Eastern Bureau of British Information Services, Vyrawalla enjoyed unrestricted access to the exclusive political circles of Delhi.

Her photographs narrate the story of India in the years leading up to Independence and during the confused but hopeful years after that.

Draped in a Parsi-style sari and lugging her heavy camera equipment around, Vyrawalla was a familiar figure in Delhi. She captured some of the most passionate moments of a young nation while she tracked events that rewrote the history of modern India.

Please click NEXT to see Homai Vyrawalla's memorable photographs...

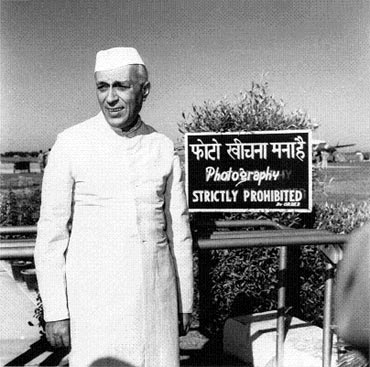

'Nehru was very photogenic'

But her favourite subject, as evident by the dozens of photographs showcasing him through the years, was India's first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru.

"He was the prime minister. The highest authority of the country," says Vyrawalla, adding candidly, "Plus, he was very photogenic."

A photograph of Nehru, releasing a dove in Delhi, is one of her favourites. It shows an exuberant, free-spirited side of Nehru that was in contrast to his carefully cultivated public image.

"He always cooperated with the camera. Anybody else would have made a fuss, but he was never bothered," she remembers.

She cites the example of a photograph in which she captured the chain-smoking premier lighting up. Nehru, who was cautious about his public image, had never been photographed with a cigarette. But he showed "no visible signs of annoyance," she recalls.

'You could see the tiredness on Nehru's face'

Eight years later, in October 1962, China sent its troops into India, triggering the disastrous Indo-China war.

"It was such a betrayal," rues Vyrawalla, recounting the damaging impact it had on Nehru, "You could see the tiredness on his face, as if he had been awake in the night. It affected his health."

Vyrawalla believed in maintaining a distance from her subjects, and never exchanged a word with Nehru in spite of chronicling him through her photographs for years.

"We were like robots. We used to take the picture and disappear," she asserts.

'I felt like a child losing its favourite toy'

One of her most moving photographs was taken moments after Nehru's death, at Teen Murti Bhavan in Delhi, where Indira Gandhi, seemingly unaware of the camera, stares at her father' body.

Her keen sense for the photographic moment often made her stay back after major events, to catch her subjects "unaware, when they were natural."

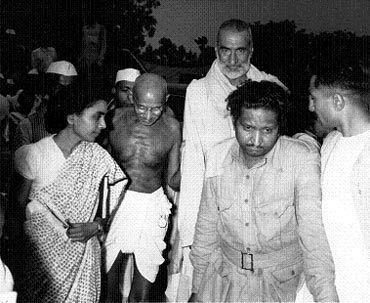

'Gandhi was like a captain leaving his damaged ship'

"My mother taught me all his morals, ideas and teachings. He was such a learned man; he asked us to be honest and helpful and not to hurt others. He taught us the value of simple living; he asked us not to lead an unnecessarily fancy life," she says fondly.

In June 1947, Vyrawalla was present with her camera at a Congress meeting, where the party's top leaders agreed to the Partition of India with a show of hands.

"The Congress had no right to give away a piece of land, as if it was their jaagir (property)," says Vyrawalla angrily. "The public had depended on them to save the country. We lost something that day."

She recalls how Gandhi came to the meeting only after the decision on Partition had been taken, and does not hesitate to criticise him for his inaction.

"He was like a captain leaving his damaged ship. He should never have agreed to the idea. He should have said, 'Over my dead body'."

She adds that no one could have foreseen the horrific violence that occurred in the wake of Partition. "With a little spark, the whole thing went wrong," is how she sums up that dark era.

'Gandhiji's last moments were not destined to be photographed'

A photographer himself, Manekshaw told her they would go to the prayer meeting together the next day.

That evening -- January 30, 1948 -- Gandhi was assassinated.

Photographs of Gandhi's last moments, Vyrawalla believes, were "not destined to be taken."

Neither were photographs of the immersion of Gandhi's ashes at the sangam in Allahabad.

The steamboats provided to the photojournalists were stuck in the sand while photographers on the shore failed to get a shot of the immersion.

Another image in her collection is one of India's last Viceroy, Lord Louis Mountbatten, at Gandhi's funeral.

"He could have stood in front of the funeral pyre. Instead, he sat down on the ground without any fuss. When he got up, he didn't even try to brush off the dirt, grass etc sticking to his clothes," remembers Vyrawalla.

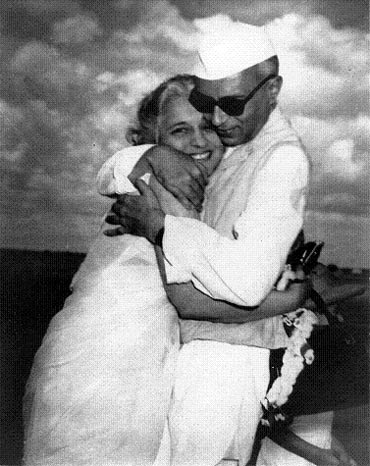

The 'Royal Photographer'

He always called her 'princess' or 'royal photographer', she recalls, and made it a point to have a word with her on every occasion.

When Vyrawalla asked why he had conferred this title for her, Dr Radhakrishnan retorted, 'Aren't you a royal photographer; don't you always take photographs of royalty?'

"They (politicians) knew exactly what to do, how to behave. They had confidence in us," she recalls of leaders of long ago. "They knew we won't intrude or impose or harm their dignity. They felt free to do what they wanted."

'We were never considered a security menace'

Until then, photographers in Delhi never had a problem getting close enough to leaders for an intimate picture.

"I have taken photographs of presidents and prime ministers from as close as five feet. We were never considered a security menace; it was unheard of. From Indira Gandhi's time, we had to stay at least 15 to 20 feet away while taking a picture," she laments.

As Nehruvian dreams faltered and cynicism replaced hope, she decided she had "done enough."

Homai Vyrawalla locked up her camera and walked away from the profession that she had dedicated much of her life to.

Click on MORE for Part II of the interview...