| « Back to article | Print this article |

'Caste as a social reality did not vanish'

Mumbai-based Anand Teltumbde is a leading scholar-activist who has written extensively on issues related to caste, class, imperialism and globalisation. In an interview with Yoginder Sikand, he talks about how globalisation has affected the Dalit movement, fighting Brahminism and the flipside of reservations

You have written extensively on what you regard as the crises facing Dalits and the Dalit movement in contemporary India, seeking to articulate a caste-class analysis of Indian society. One of your major focuses has been the challenges Hindutva poses to the Dalits. You regard Hindutva as extremely inimical to Dalit interests and their struggle against upper caste/class hegemony. Given, as you have written, that Hindutva groups have made deep inroads among Dalits, how do you feel a progressive counter-cultural alternative can be presented to and popularised among Dalits in order to counter the attraction that Hindutva seems to offer them?

While Hindutva is a form of Brahminism and is definitely geared to suppressing the Dalits and serving the interests of the upper caste/class elites, one should be clear that Hindutva is not entirely a cultural phenomenon. It is more of a political phenomenon. So, challenging Hindutva cannot be limited only to articulating a counter-cultural alternative, as some have sought to do in the name of Dalit identity-politics. Rather, Hindutva needs to be challenged politically.

As regards a counter-culture to Hinduism from the Dalit perspective, I am not sure if we have the resources for this or if sufficient attention has been paid to how to popularise this alternative given the immense hold of the Hindu framework. We may say, and rightly so, that the conflict between Brahminism and Shramanism, as represented by Jainism and Buddhism, has been present throughout Indian history.

On this basis, we may invoke the Shramanic tradition to critique Brahminism. However, we also have to admit that despite the immense popularity of the Shramanic traditions for over 10 centuries, the Brahmanic castes have survived; nay, they have thrived. How does one explain it? These religions -- particularly Buddhism -- did offer alternatives to Brahminism at the philosophical level but, despite this, caste as a social reality did not vanish. I think the same can be said of the conversion of Dalits to other religions as a means for liberation from caste oppression.

Dalits have converted to Islam, Christianity, Sikhism to escape caste bondage of Hinduism but this did not make much difference to their lives. Caste has rather infected these seemingly egalitarian religions, keeping its Dalits at the lowest rungs. In objective terms, not much has changed for the converts. While they continue to remain Dalits for others, among themselves they appear to follow the same cultural paradigm laid out by the Hindu framework, albeit with cosmetic changes.

Babasaheb Ambedkar did expect a new cultural paradigm for the Dalits based on scientific rationality, but it remained an unfulfilled dream like many others. That is perhaps why many Dalits in Maharahstra have, unfortunately, not been averse to joining hands with Hindutva forces. Even many well educated Dalits with some social recognition did not see anything wrong in jumping onto the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh's Samarasata platform which talked of the 'unity' or 'assimilation' of castes.

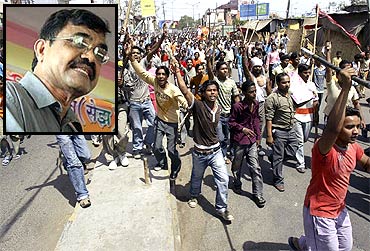

Politically, Ambedkarite Dalits have been joining the Hindutva forces with impunity. The current alliance between Ramdas Athavale's Republican Party of India and the Shiv Sena-Bharatiya Janata Party combine under the guise of Bhimshakti+Shivshakti is a case in point. The fact that there is not much opposition to such ideas and actions bespeaks volumes about alternative culture. So, I would say, the hegemonic influence of the Hindu or Brahminical worldview still remains, and Dalits, as a whole, continue to operate within that cultural framework.

'Reservations left the really needy out of its reach'

If that is the case, then what is the alternative in terms of a counter-cultural challenge to Hindutva?

I think the alternate is only possible from the Left -- not the parliamentary Left that still appears to cling to the idea, notwithstanding their wordy acrobatics, that religion and caste are simply 'superstructural' issues or of little or no importance, but a Left that is rooted in Indian social realities and recognises the salience of these issues. Fortunately, some sections of the radical Left are developing such an understanding organically. If Dalits also review their journey so far objectively, I am sure they also will reach a similar radical understanding.

That said, I do not negate the importance of culture in both perpetuating as well as challenging an oppressive system, but, at the same time, I disagree with some Dalit ideologues who insist that cultural revolution must necessarily precede political revolution. The two must go together, working in a dialectical fashion.

Alternate cultures do not develop in vacuum, just by wishing for them. They are born in the process of peoples' struggles over the material issues of their living -- essentially politico-economic struggles. I am sure the counter-cultural to Hindutva will also emerge from these sorts of mass-based struggles. I don't see it as a question of one preceding the other in time in a mechanical way.

Some analysts argue that while focusing mainly on the issue of reservations and critiquing Brahminism, sections of the Dalit movement have ignored the material issues and concerns of the Dalit poor. Do you believe in that analysis?

There is considerable truth in that assertion. By and large, the Dalit movement has been led and controlled by urban-based petty bourgeoise Dalits, and has tended to neglect Dalits living in villages. If you consider the demographic profile of Dalits, you will find that Dalits are predominantly rural people; some 89 percent of them still live in villages. More than half of them are landless, 26 percent are marginal farmers and the rest are artisans. Of the 11 percent urban Dalits, a vast majority lives in urban slums and work preponderantly in the informal sector.

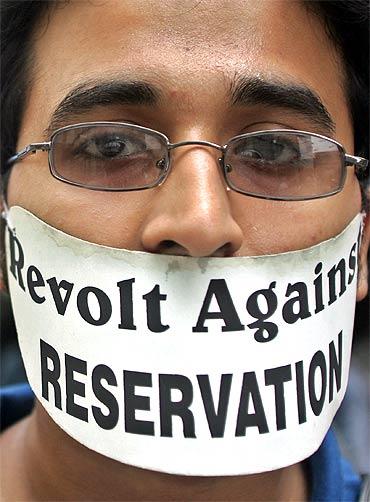

Over the last six decades, a small layer -- certainly not exceeding 10 percent of the total -- has emerged out of them who could be considered as 'arrived', thanks to reservations, political nexus and their enterprise. This small layer, however, has effectively hijacked the agenda of the majority of the Dalits and revolved it around the single issue of reservation. It reflects the urban and class bias of the Dalit movement that has persistently ignored the issues of rural Dalits.

Reservations did have a utility for the first generation of Dalits but thereafter it increasingly became the monopoly of those who have come up, leaving the really needy out of its reach. It is a widely acknowledged fact that the caste issue is entangled with the skewed distribution of land or the high incidence of landlessness of Dalits.

Even Babasaheb Ambedkar, towards the end of his life, had realised this fact and influenced some of his followers to take up the first land struggle in Marathwada. Thereafter, Dadasaheb Gaikwad, who was his close confidant and perhaps his real political heir, had led a countrywide struggle for land. But, thereafter, we never hear of the land issue being raised within and by the Dalit movement.

Lack of land, quality education, non-farm employment, proper housing and sanitation are the material issues that have historically been related to Dalit deprivation, and these have only been aggravated by the elitist globalisation over the last two decades. There is not a slightest reflection of these issues in the dominant Dalit discourse.

Surprisingly, when reservations have effectively ended -- statistically, from 1997 onwards the total employment in the public domain has been consistently decreasing -- they shout louder about it.

So, yes, I sincerely think in the post-Ambedkar phase, the Dalit movement, driven by small elite among the Dalits, has completely ignored the material issues of most Dalits.

'The issue of landless Dalits is taboo'

But now that government jobs are rapidly shrinking in the wake of privatisation and globalisation, which means that jobs for Dalits in the public sector are even more limited than they hitherto were, do you see a shift in the focus of the Dalit movement? Given that globalisation and privatisation are hitting the poorest of the poor, particularly Dalits, is the Dalit movement responding by widening its concerns and addressing the challenges posed by globalisation, thus moving out of what you consider as its major concern with reservations?

I do not see a major shift happening, barring the fact that Dalit groups are now demanding reservations in the private sector and curiously campaigning about 'Dalit Capitalism'. This, once again, illustrates their elite, urban focus. I do not see them interrogating globalisation and mobilising Dalits against the havoc that is causing to the poor, leading to mass pauperisation and rapidly widening social-economic inequalities.

Statistics reveal that the incidence of landlessness has been increasing among Dalits during the last two decades of globalisation. But they are oblivious of these facts. The question of land, or the issue of landless Dalits and their forced displacement by mega-projects, has been a virtual taboo in the Dalit movement because most Dalit 'leaders' think it is a 'communist' issue. They have been programmed into believing that communists are their enemies! They have been fed on lies, by many Dalit intellectuals and leaders, that Babasaheb Ambedkar was viscerally opposed to communism as such --although it is well-known that Babsaheb did see the importance of land issue and was a confirmed socialist, as is evident from his monumental book States and Minorities.

They have systematically constructed an Ambedkar icon sans the radicalism of Ambedkar, with superfluous embellishments of Ambedkar ideology, projected it as a virtual god-like figure to the Dalit masses, and invoke it in support of whatever they do.

'Many Dalits today unconsciously act against Ambedkar'

This icon is used and duly supported by the ruling classes to build a kind of bhakti cult in the Dalit masses. Now, it is absolutely clear that Babsaheb hated the bhakti cult around him and explicitly said that that he did not want bhaktas but sincere followers. This cult facilitated 'brokers' among Dalits to sell their wares in his name, and the Dalit masses simply bought their wares. This is the unfortunate paradigm that has degenerated the Dalit movement and has effectively thwarted sincere elements from coming up.

It is entirely because of this that there seems to be little or no effort to re-read or contextualise Babasaheb's thoughts in the contemporary context, including on issues related to class-based deprivation. At a time when the Indian State, Hindutva forces and the forces of imperialism are playing such havoc with the livelihoods of millions of Dalits, whose condition is rapidly going from bad to worse, I see few Dalit groups taking these crucial economic issues seriously.

Instead, they remain fixated on reservations -- because this is a convenient populist slogan -- and on invoking the name of Babasaheb while refusing to re-read him in the context of the contemporary situation of caste/class deprivation.

Babasaheb Ambedkar said that he was against Brahminism and not Brahmins, and even explained that Brahminism could be found in any caste, including Dalits. Dalits have conveniently forgotten this essence and picked up the superficial. Today, the situation is such that groups whom they include in their Bahujans, the superset of Dalits, are the real perpetrators of atrocities on Dalits. They are the real baton holders of Brahminism in villages.

But these political-economic analyses just do not appeal to Dalits, who are enamoured with identitarian discourse. To oppose Brahminism is to be anti-caste; but to hate Brahmins is casteist. Paradoxically, swearing by Ambedkar, many Dalits today unconsciously reflect casteist behaviour, and thus act against Ambedkar.

That said, we must remember that the anti-materialist outlook of Dalits is actually born out of their encounter with the Left movement, which refused to acknowledge the caste question as something basic to the class struggle in India. Babasaheb Ambedkar was no Marxist. He had genuine problems with Marxism but at the same time he ardently believed in socialism of the Fabian kind. This was a good enough basis for working together with the Left and enriching the strategy for class struggle in the concrete situation in this country.

But the Left continued undermining the Dalit movement and, in the process, completely alienated it. The onus thus squarely lies with the Left for the fact that today we are faced with the divergent, almost antagonistic, movements of the proletariat, bogged down with an idiotic duality of class and class.

The Left movement needs to rethink its perspective on the Dalit question. There is an urgent need for a dialogue between the Dalit movement and the Left, so that they can learn from each other and cross-fertilise each other. This will certainly help the Dalit movement in responding in a more appropriate manner to the changing nature of caste and helping it realise the importance of class issues and the need for class-based mobilisation as well. I am uncomfortable with Dalit identity politics which only make the Dalit movement more sectarian and lead it away from the material problems, as experience shows. Caste as essentially a divisive category cannot viably serve even identity politics, not to speak of the goal of annihilation of caste. I am surprised that this basic understanding is yet to dawn on our social scientists as well as activists.

On Wednesday, read the impact of the Dalit media, NGOs and Dalit capitalism on the movement in part 2 of the interview with Anand Teltumbde