Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Joseph Lelyveld has three words for those who have banned or sought to ban his book Great Soul - Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle with India: "Read it carefully."

Speaking to Rediff.com from his New York home, he says the passages about Mahatma Gandhi's friendship with Herman Kallenbach, the German architect Gandhi lived with for about four years in Johannesburg, that have offended some people -- who probably haven't read the book -- have been misunderstood, and in two specific cases, deliberately distorted.

"I never wrote that Gandhi was bisexual," Lelyveld, who turned 74 two days ago, says, adding that he had never expected the book, which has garnered praise from authors like Hari Kunzru and Amartya Sen, to create controversies.

The book has been banned in Gujarat, though the central government has refused a nationwide ban, and Gujarat Chief Minister Narendra Modi's comments have been widely reported in America.

'It has hurt the sentiments of those with a capacity for sane and logical thinking,' Modi was quoted as saying. 'The writing is perverse in nature.'

An Indian cultural association in Santa Clara, California, which had invited Lelyveld to read from the book, cancelled the event fearing its fundraising event would become controversial.

The author blames The Wall Street Journal and Daily Mail newspapers for using the book review -- most of the others have been flattering -- to distort things to serve the personal agenda of the reviewers, which was to trash Gandhi. "And then it became viral," he adds.

The The Wall Street Journal review says that Great Soul provides evidence that Gandhi was 'a sexual weirdo, a political incompetent, and a fanatical faddist.'

"The Daily Mail said that Gandhi had left his life for a gay lover. I never said Kallenbach and Gandhi were gay. I also quote their discussion on sexual abstinence," Lelyveld says.

'It was perhaps the most intimate relationship in Gandhi's life'

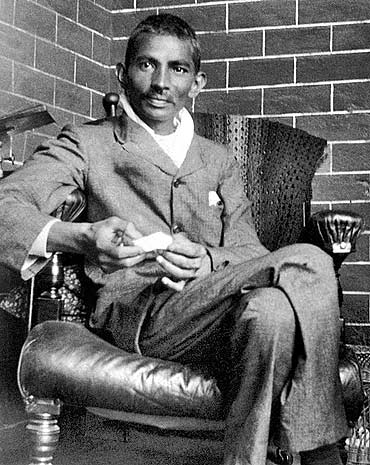

Image: Herman KallenbachPhotographs: Isa Sarid/GandhiServe

Joseph Lelyveld, a former executive editor at The New York Times, came across Gandhi's letters to Kallenbach in the Indian government archives. 'Your portrait (the only one) stands on my mantlepiece,' Gandhi wrote from a London hotel room in 1909. 'The mantelpiece is opposite to the bed Cotton wool and Vaseline are a constant reminder.'

Lelyveld quotes another passage that some people may think suggests an erotic relationship between the two men. The point is, Gandhi wrote, '"to show to you and me how completely you have taken possession of my body.'

Gandhi destroyed the letters Kallenbach wrote to him, but the latter kept Gandhi's letters.

'What are we to make of the word 'possession' or the reference to petroleum jelly, then as now a salve with many commonplace uses,' Lelyveld says in his absorbing, scholarly, endlessly intriguing and revelatory book, which is never sensational.

'The most plausible guesses are that the vaseline in the London hotel room may have to do with enemas, to which he regularly resorted, or may in some other way foreshadow Gandhi's enthusiasm for massage arousing gossip that has never quiet died down, once it became clear that he mostly relied on the women in his entourage for its administration," he said.

They were a couple, Tridip Suhrud, a Gandhi scholar told Lelyveld in Gandhinagar, but he never suggests anything sexual happened between the friends.

'One respected Gandhi scholar characterised the relationship as "clearly homoerotic" rather than homosexual, intending through that choice of words to describe a strong mutual attraction, nothing more,' Lelyveld noted in his book.

But gossip was rife. 'The conclusions passed on by word-of-mouth in South Africa's small Indian community were sometimes less nuanced. It was no secret then, or later, Gandhi leaving his wife behind had gone to live with a man,' he added.

The relationship between Kallenbach and Gandhi would have become stronger had the former not got involved in the Zionist movement that would lead to the creation of Israel, Lelyveld says.

"I realised when I was writing the Kallenbach pages that though this was only a few pages, really, it was also sensitive material," says Lelyveld.

'I didn't imagine that people would be astounded or offended'

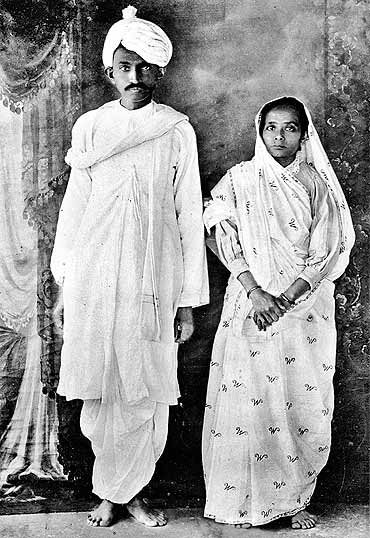

Image: Gandhi, now the Mahatma, with his old friend Herman KallenbachPhotographs: Isa Sarid/GandhiServe

He writes that Gandhi and Kallenbach discussed celibacy and the vegan way of life. Kallenbach wrote to his brother that while living with Gandhi he had given up meat and fish, and he pointed out to Gandhi how milk could arouse body appetites.

Gandhi's concern about sexual abstinence is also revisited at length in the book. Some of his experiments including testing his renunciation of sex by sleeping naked with his grandnieces upset followers. Nirmal Kumar Bose, 'the detached Calcutta intellectual' serving as Gandhi's interpreter, was one of them.

'After a life of prolonged brahmacharya (self-imposed sexual abstinence), he has become incapable of understanding the problems of love or sex as they exist in the common human plane,' Bose wrote in his diary.

Bose tried to acquaint Gandhi with psychoanalytic concepts of the subconscious, neurosis and repression. He asked Gandhi about the people who did not have his motivation or strength, Lelyveld says. "Gandhi came across a single reference to Freud in one of Bose's letters," he adds.

"Gandhi had read Havelock Ellis and Bertrand Russell on sex, but not Freud. He said, 'Tell me more about Dr Freud. What is Freudian philosophy? I have not read any writing of his.' Gandhi was always curious about new thoughts and ideas."

Lelyveld's interest in Gandhi dates back to tours in India and South Africa as a correspondent for The New York Times, where he worked for nearly 40 years, becoming the executive editor from 1994 to 2001. His book on apartheid, Move Your Shadow: South Africa, Black and White, won the Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction.

Writing the 426-page Great Soul involved perusing thousands of documents, reading dozens of books on Gandhi, visiting the many sites associated with him in South Africa, India and Bangladesh. In addition, Lelyveld discussed Gandhi with scholars in South Africa, India and the United Kingdom, and the Mahatma's descendants.

The new book is published in America by Knopf, which is headed by New Delhi native Ajai Singh 'Sonny' Mehta. Knopf has published works by Nobel Laureates like V S Naipaul, Orhan Pamuk and Amartya Sen, and other distinguished and provocative writers like Salman Rushdie, whose The Satanic Verses was banned in India, and Rohinton Mistry, whose Such A Long Journey was removed from the Mumbai University curriculum last year under pressure from the Shiv Sena.

Researching the book and writing it challenged Lelyveld considerably, and it would do so to any open-minded reader, he says. Gandhi is like a replica, he writes in the Author's Notes, 'fenced off from our surroundings and his times. The original, with all his quirkiness, elusiveness, and genius for reinvention, his occasional cruelty and deep humanity, will always be worth pursuing. He never worshipped idols himself and generally seemed indifferent to the clouds of reverence that swirled around him. Always he demanded a response in the form of life changes. Even now, he doesn't let Indians -- or, for that matter, the rest of us -- off easy.'

'I am trying to look at his life in a different way'

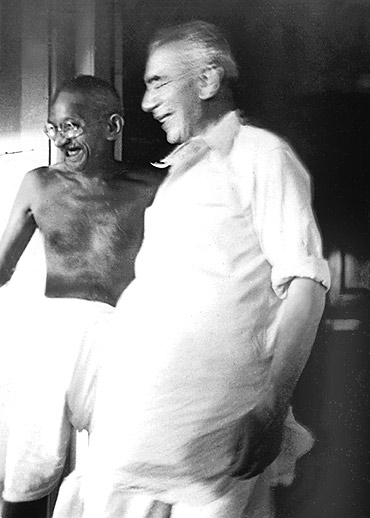

Image: http://im.rediff.com/news/2011/apr/06gandhi3.jpgPhotographs: Mahatma Gandhi was a fine and prolific writer

"I'm trying to look at his life in a different way; and supplement it with a story that I think has always been there, but always been neglected. And that's the story of the evolution of Gandhi's social values, and, much of which, not all of which, occurred in the 21 years in South Africa. Obviously, at 44 (when he returned to India in 1914) he was a very different man to the 23-year-old just-returned-barrister who arrived in Durban in 1893."

Gandhi's transformation started in London where he arrived in 1888, at age 18, without his wife and newborn son, to study law.

For some months, he sought to emulate English men, buying finely tailored suits, fine-tuning his accent, learning French, and taking violin and dance classes. But soon he decided such persuasions were a waste of time and money and concentrated on his studies. He landed in South Africa after a short sojourn in India as a lawyer.

'South Africa, by contrast, challenged him from the start to explain what he thought he was doing there in his brown skin,' Lelyveld writes. 'Or, more precisely, in his brown skin, natty frock coat, striped pants, and black turban, flattened in the style of his native Kathiawad region, which he wore into a magistrate's court in Durban on May 23, 1893, the day after his arrival.'

An incident occurred in court, which Lelyveld believes has not been given attention by historians. The magistrate took Gandhi's turban as a sign of disrespect and ordered it to be removed.

When Gandhi stormed out of the courtroom, The Natal Advertiser newspaper wrote a piece headlined: 'An Unwelcome Visitor.'

Gandhi, who would become a prolific letter writer, wrote to the publication, 'Just as it is a mark of respect amongst Europeans to take off their hats, an Indian shows respect by keeping his head covered In England, on attending drawing-room meetings and evening parties, Indians always keep the head-dress, and the English ladies and gentlemen seem to appreciate the regard which we show thereby.'

'Gandhi had clearly flirted with the idea of conversion'

Image: Mohandas Gandhi in 1908Great Soul also looks deeply at Gandhi's interaction with Christianity. "Gandhi had clearly flirted with the idea of conversion when he was in Pretoria," the author says. "He went to the church on Sundays; in fact, he was on one occasion barred from a church in Durban (because of his race). His religious life revolved around Christianity for some time, but he finally gave up on the idea of converting. Perhaps it was a political calculation."

In Great Soul, Lelyveld quotes Millie Polak, the wife of a British lawyer who was part of the inner circle for Gandhi's last 10 years in South Africa.

She remembers Gandhi as saying, 'I did once seriously think of embracing Christianity I was tremendously attracted to Christianity, but eventually I came to the conclusion that there was nothing really in your scriptures that we have not got in ours, and that to be a good Hindu also meant I would be a good Christian.'

Late in 1894, Gandhi also flirted with the Esoteric Christian Union that sought to reconcile all religions.

He identified himself proudly as an 'Agent for the Esoteric Christian Union and London Vegetarian Society.' The unification of faiths became a close spiritual issue for him.

'It's a theme,' Lelyveld writes, 'Gandhi would repeat at prayer meetings in the last years of his life.'

'Gandhi was aware of what was happening to the blacks'

Image: Mohandas and Kasturba Gandhi after returning to IndiaBut Gandhi's admiration for the Gospels and the Sermon on the Mount remained firm. "Sri Aurobindo said, 'Gandhi was a Russian Christian in an Indian body,'" Lelyveld says. It was a reference to Tolstoy's influence on Gandhi.

Great Soul could revive the controversy over Gandhi's contemptuous words for South African blacks during his early years there.

"Gandhi was aware of what was happening to the blacks in South Africa; he supported the growing movement (against white domination), but he had no close black friends," Lelyveld says.

"His home in Phoenix settlement was very near the home of African National Congress founder John Dube," Lelyveld notes. "Gandhi was an avid walker and he would have crossed Dube's house a thousand times. They kept a distance."

'Gandhi said things that are difficult to justify'

Image: Mohandas and Kasturba Gandhi in South AfricaAfter hearing Dube, an ordained Congregational minister, speak at the house of a white planter and civil leader, Gandhi wrote in Indian Opinion, 'This Mr Dubey (sic) is a Negro of whom one should know.'

>The article had 'an unfortunate headline,' Lelyveld says. The Kaffirs of Natal.

"And Gandhi called Dube the leader of 'educated Kaffirs,' which demonstrates that for him the world applied to all blacks, including Congregational ministers and headmasters, not merely unlettered tribal Africans," he adds.

Gandhi's summary of the speaker's remarks was respectful and sympathetic. 'They worked hard and without them the whites could not carry on a moment,' Gandhi wrote.

When Gandhi was imprisoned with Zulu convicts for his political activities, he wrote that 'Kaffirs are as a rule uncivilised -- the convicts even more so. They are troublesome, very dirty and live almost like animals.'

"Gandhi said things (against blacks) that are difficult to justify, and which are now embarrassing," Lelyveld says. "Efforts are made to rationalise it, but the efforts are not effective But there is some justification in looking at Gandhi as a founding father of South Africa."

"Gandhi came back to India with a set of social values that would lead to a widespread movement for not only political change, but also a widespread movement for social change," adds Lelyveld, "which was basically targeted at caste Hindus."

'Gandhi was listening to the truth'

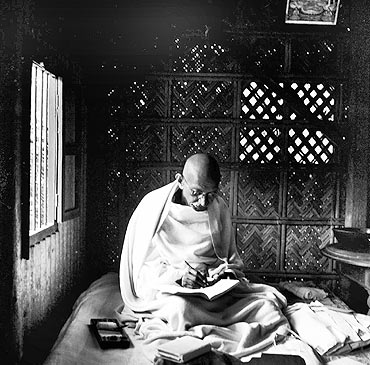

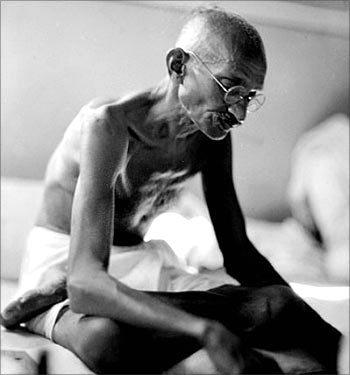

Image: Mahatma Gandhi"And, in my mind, that makes it a somewhat tragic story, inspiring but somewhat tragic, because he started with this vast, one would say, utopian dream of a widespread social transformation and then discovering that in many respects it had not occurred and that the people who proclaimed to be his followers, very often, were just paying lip service."

How does Lelyveld assess Gandhi's work in the present Indian context?

"The country has long accepted Gandhi was right morally," he says, "and therefore he won the argument. On one level, people's thinking changed, but not their practice. But when you look at the vastness of India with 1.2 billion people even if he deeply influenced 10 percent, it is a lot of people."

Lelyveld remembers meeting a Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh historian at the RSS headquarters in Nagpur, Maharashtra, and coming to the conclusion that the movement, which isn't conventionally considered pro-Gandhi, has long changed its view on the Mahatma. "In recent decades, it has been mentioning his name in its daily roll call of Hindu heroes," he says.

Even after Gandhi began to realise that many people were not willing to follow his call for a radical social change, he kept persisting. 'It is enough if I am my follower,' he once said.

"Gandhi was listening to the truth," says Lelyveld. "Mohammad Ali Jinnah, on the other hand, was looking for deals."

With his long association with India, Lelyveld feels "that the term Gandhian has become ultimately synonymous with social conscience; his example -- of courage, persistence, identification with the poorest, striving for selflessness -- still has a power to inspire, more so even than his doctrines of nonviolence and techniques of resistance, certainly more than his assorted dogmas and pronouncements on subjects like spinning, diet, and sex."

"It may not happen often," says Lelyveld, "but the inspiration is still there to be imbibed, and when it is, the results can still be called Gandhian, even though the man himself, that great soul, never liked or accepted the word."

article