| « Back to article | Print this article |

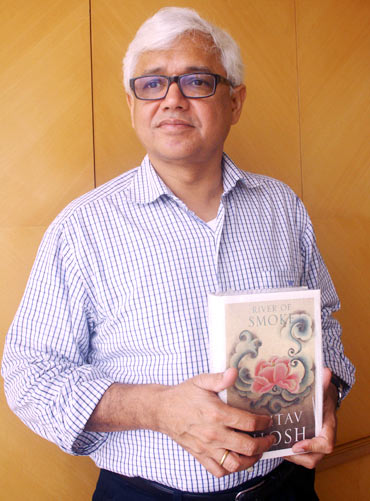

Yet again, Amitav Ghosh sails on opium

Man and opium have a relationship that goes back to the infancy of mankind. Human civilization is inconceivable without it,' Amitav Ghosh said during an interview with an American radio station in 2008, shortly after the release of Sea Of Poppies (Penguin/ Viking, 2008).

The acclaimed novelist, who was shortlisted to win the Booker Prize in 2008, painted the first volume of his celebrated Ibis trilogy on an expansive and exquisitely detailed canvas, plotting his epic tale against the backdrop of two great Opium Wars, which the British Empire fought in the 1830s to subdue an impregnable and indomitable China. Under the premise of free trade, the British East India Company and other Western mercantile institutions with similar vested interests employed opium to enter the Dragon, and to eventually tame it. Indeed, Ghosh reminds us that the plotters of these wars believed that opium was 'God's instrument for opening the Chinese oyster.'

Ghosh's picturesque prose transports the reader from the poppy fields of impoverished Bihar to the great opium factory at Ghazipur, Bengal (which stands to this day), and then amid a great ocean of characters aboard the Ibis, where a curious breed of Indian Ocean ship-people, the Lascars, cuss richly in their peculiar patois.

The climactic finale of Poppies saw some of its characters sail away from the Ibis, which had departed from Calcutta bearing both opium and indentured labourers drafted for the plantations of Mauritius. Readers who expect seamless continuity in River Of Smoke (Penguin/ Viking, 2011) might be surprised to discover that the second book picks up the thread in another time and place. Ever the artful storyteller, Ghosh departed from the idea of a sequential trilogy, choosing instead to regale his readers with three wholesome books peppered with mirrors, windows and trapdoors into each other.

In Mumbai for the launch of River Of Smoke, Amitav Ghosh spoke to Bijoy Venugopal about the art of writing a trilogy, his dramatic characters, the nuanced language they speak, and the Imperial intrigues that culminated in the Opium Wars.

Excerpts:

The second volume of the Ibis trilogy is heftier than the first -- was it harder to write?

Every time I finish a book, I think it was impossibly difficult to write. Especially with Sea Of Poppies, where the ending is finely orchestrated with everything coming together, I felt it was the most difficult thing I'd ever done. And now, I feel the same way about River Of Smoke. It was incredibly challenging, in exciting ways, but difficult nonetheless.

Have you decided you will stop at a trilogy?

(Laughs) I haven't decided anything. When I write the third book it will, willy-nilly, be a trilogy. But I can write another one, and another. Maybe a trilogy of trilogies!

You mentioned recently that the books are not linked in a linear manner but thematically, like Lawrence Durrell's Alexandria Quartet. What did you mean by that?

I don't want (the books) to be a series of episodes connected in a direct way -- not like, say, Star Wars. Each of these books is a novel in its own right. Even though Sea Of Poppies is the first, I don't think it should necessarily be the first to be read. And the way it is played out with River Of Smoke, it's leading many new readers to Sea Of Poppies.

Many of the same characters are there in River Of Smoke but there are recaps where you can see into their past lives...

That's right. The characters are there but they're much older, they're much changed, they're different people at this point. And that's what I wanted -- to be able to enter and re-enter the story at different moments in time. With River Of Smoke, some aspects of fitting together happened in the first chapter. With the [next book], even that need not be there, I think. I'd feel perfectly free to start somewhere else.

How to tame the Dragon

Two Opium Wars, also known as the Anglo-Chinese Wars, were fought between the British Empire and China from 1839 to 1842, and from 1856 to 1860. Oddly, the genesis of these wars can be traced to an innocuous but lucrative commodity produced in China -- tea. The humongous demand for it in Europe caused a massive economic deficit as European nations bought it with large quantities of silver. However, doing business with China was far from simple.

The Canton System, put in place by the Emperor of China in 1756, forbade Europeans from entering the country and restricted business to one port, Canton, on the mouth of the Pearl River. European merchants, including the English East India Company, were permitted to trade only on the island of Macau.

Led by the English East India Company, European and American traders strategically and stealthily exported opium, produced for a pittance in British India, to China where it was an illegal commodity. By infiltrating the system and creating an enormous demand for the drug, which fetched huge prices, Western traders set up a sophisticated smuggling operation that frayed relations between the two powers and escalated into war.

China suffered heavy military losses and, in the 'unequal treaties' that followed, the Qing Dynasty was forced to cede territories at the mouth of the Pearl River to Britain and legalise the opium trade, with enormous advantages to Britain.

Interestingly, opium was not foremost on Ghosh's mind when he embarked on his trilogy. Fascinated with the subject of departures, he was researching the lives of Indian indentured workers who left India from the Bihar region when it struck him that all roads led back to the nefarious drug trade. As he remarked in an interview to the BBC, 'There was no escaping opium.'

In Sea Of Poppies, Ghosh describes the journeys of such indentured workers as well as the machinations of the opium factory at Ghazipur.

In River Of Smoke, he speaks of opium's surreptitious odyssey along the Pearl River into the dens and parlours of mainland China, and we learn that Bombay, Hong Kong and Singapore were focal points of a 'diabolical' opium empire that Britain adroitly established to subdue China.

What role did the Pearl river play in the opium trade?

The Pearl river was like a funnel through which goods entered and exited China. If you think of the geography of it, it is a triangle with Macau and Canton at either end of the mouth of the Pearl river, and Hong Kong at the other end. It's a beautiful, dramatic landscape. As you go inland, the Pearl river narrows and grows more crowded until it reaches Guangzhou, which is Canton.

The opium trade was declared illegal by the Emperor of China in the 1730s. The East India Company found a way of beating Chinese regulations -- (the traders) would take the opium to a little island at the mouth of the Pearl river. You can still see this island -- it's called Lintin island.

The Chinese, in that period, did not exercise authority on offshore islands. The mainland was strictly under their control but they considered a lot of the islands interstitial and did not try to extend their authority to them.

The mouth of the Pearl river is dotted with thousands of islands, which in those days were used by pirates. The British -- and the Americans -- took advantage of this. They took big ships to Lintin island, anchored them there, took off their masts and left the hulls.

The hulls became 'receiving ships' -- they were like floating platforms. The British, Americans and Indians would pick up opium from Bombay and Calcutta, take it to Lintin Island and offload all of it onto these ships. Then, once their holds were clean, they would approach the Chinese customs office, and say, 'We have no opium.'

Ingenious, I must say!

It's very ingenious, and completely diabolical! Lintin island is not far from the shore and from those ships, the merchants would carry away the opium in fast-crabs, which were very fast boats with about 60 oarsmen.

The opium would be taken to the mainland but the merchants, as far as they were concerned, had their hands clean. It was a very sophisticated smuggling operation.

You spoke of Mumbai (then Bombay) as a city that the East India Company bankrolled from Bengal to keep the opium trade alive. Are there parallels to be found in other cities of the Opium empire?

Absolutely.

According to a famous historian Amar Farooqui, who's written a very good book (Opium City -- The Making of Early Victorian Bombay, Three Essays Press, 2006), in the 18th century, Bombay didn't have much future, which is why the Portuguese were willing to give it away.

The British also found it very expensive to maintain -- it was a malarial and not particularly hospitable string of islands and they were thinking of withdrawing from it. It was in this period that the opium trade picked up in Bengal and a lot of it began to go through Bombay. Because of opium, Bombay suddenly became economically viable.

You could say that all the most important financial cities of today's Asia owe their existence to opium -- Bombay, Singapore, Hong Kong, Shanghai... you can add Guangzhou to that list. These are the cities driving the world economy.

Was there an echo of the opium trade in the New World?

(Laughs) Not just an echo, they were enthusiastic opium traders!

Virtually the whole of the East Coast of America -- all their major institutions and major families -- were deeply involved in the opium trade. For instance, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, perhaps their greatest President of the twentieth century -- his grandfather, Andrew Delano, was one of the major traders in Canton. Where do you think the Roosevelts made their money from?

I've seen letters from the Coolidges - who also had a president (Calvin Coolidge, the 30th US president) -- who came from Canton to Bombay to pick up opium. One of the Coolidges even lost his money in Bombay.

Repeatedly, when I look at the lives of American opium traders, I see that they made their fortune in China, went back to America, and then endowed universities, schools and colleges. A lot of the American educational system was funded by opium.

There is an undercurrent of sharp criticism of the Empire and imperialism in your books. Was it Oxford that shaped this attitude?

Not really. If there's one thing that you learn from history, it's that pretty much everyone was pretty bad (laughs). I don't think we were that much better. The Chinese weren't great, either.

What is so peculiarly repellent about the British Empire is the hypocrisy that goes with it, this whole rhetoric of 'we're doing this for your good, to make you free, and to promote harmony and goodwill' when it's the worst kind of greed and venality and racism.

That greed, venality and racism should exist is not surprising -- it exists everywhere. But most people don't cloak it by talking constantly about how that's a good thing. So, it's the hypocrisy that appals me so much.

The India in Mauritius

Though the Indian Ocean island of Mauritius is a popular tourist destination, few imagine that its past lies shrouded in imperial subjugation, indentured labour and a heart-breaking struggle for liberty.

The island's sugarcane plantations, set up by the French East India Company in the 1720s, passed into British hands after the Napoleonic Wars a century later. Slaves from India, China and Africa, who were employed on these plantations, escaped to the remote mountainous peninsula of the Morne Brabant, seeking safety in its inaccessible caves.

In February 1835, after the official abolition of slavery, a police expedition approached the Morne to inform the fugitives that they were now free. Mistaking their approach for threat, thousands of escapees leapt off the cliffs to their death. Commemorating that event, Le Morne Brabant was declared a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2008.

Another site of importance to Mauritians of Indian descent is the Aapravasi Ghat, earlier known as Coolie Ghat. Located in Port Louis, it was the landing point for slaves entering Mauritius.

River Of Smoke opens in the dramatic landscape of the Morne, many years after the great tragedy. Studying the journeys of indentured workers from economically depressed Bihar and Bengal in the wake of the 1857 nationalist uprising, Ghosh was awakened to the curious and moving umbilical bond they had established with their roots.

When you visited Le Morne Brabant and Aapravasi Ghat in Mauritius, what evidence or relics did you find that supported your story?

I went to many houses of Indian descendants and, very often, their walls were painted in ways that were reminiscent of the Madhubani style and (the art) of the Bhojpuri-Maithili region. (The immigrants) brought it with them from Bihar.

Mauritius is very beautiful and the landscape is filled with peculiar twisted rock formations completely unlike anything that you would see in India. The Morne Brabont is a completely wind-battered, haunting and desolate place on the southwest tail of Mauritius. The story that I told in the book is true -- the runaway slaves used to hide on this mountain because it was so inaccessible.

The first time I went to the Morne Brabont, I was taken there by a family of Indian descent. The plantation, right there at the foot of the mountain, had passed into their family's hands.

The trilogy seems to be as much a story of opium as it is of a world shaped by voluntary and forced migrations. Would you agree that, like many Indian authors, you are deeply concerned and curious about our Diaspora?

To me, the Indian Diaspora is a very fascinating subject and one to which I have returned time and again. And curiously, it's because I am myself not from the Diaspora. My interest in it is from the Indian end of things.

Chai and samosas, words and awards

Much feted for both his fiction and non-fiction, Ghosh was awarded the Blue Metropolis International Literary Grand Prix (2011) and the Dan David Prize (2010) among a number of literary awards.

His first novel The Circle Of Reason (Viking/ Ravi Dayal, 1986) won the Prix Medicis Etrangere, the prestigious French literary award whose recipients include Philip Roth, Michael Ondaatje, Doris Lessing and, more recently, Orhan Pamuk. Ghosh maintains that while he welcomes such honours, they do not influence his writing or his choice of themes.

Ghosh's novels are treasures for the word-enthusiast, full of etymological discoveries and cleverly woven anecdotes about the roots of loanwords. These words come to life in the quaint dialects of characters such as the Parsi merchant Bahram Modi, the East Indian Vico from Bassein (present-day Vasai, a far-flung suburb of Mumbai), and Robin Chinnery, the fictitious son of a real painter, George Chinnery, who lived in Calcutta before moving to Macau where he died in 1852.

The Ibis Chrestomathy, maintained by Raja Neel Rattan Haldar, a character in the trilogy, offers a lexicon to this strange language.

In conversation, Ghosh points out that some our simplest everyday words -- such as cheeni (white sugar that was imported from China) -- have made great journeys.

In the course of writing, did you discover words that sparked off new ethnographic discoveries?

So many. The simple things in our lives. Look, here we are sitting drinking chai. Where does the word chai come from? It's Cantonese.

Words for tea come either from the Fukienese, which is te, or from the Cantonese, which is cha. Around the world, cultures took them and turned them into either tea or chai.

And samosa -- essentially, it comes from samsa, a Xinjiang dish...

There's a sambosa in Afghanistan...

That's right. It's actually from the Turkic Uighur, from the Xinjiang area. We adapted it and turned it into our own little thing. But samosas aren't ours. They're actually Turkish...

Poppies was short-listed for the Booker Prize. Were you disappointed at not winning?

(Laughs heartily) Not in the slightest! I was absolutely sure I wouldn't get it. The only awful thing about it is that you're sitting at a table with all these publishers and they really want it. I felt bad for them. I wanted to pat them on the back and tell them not to be disappointed.

I was very glad for Aravind Adiga that he got it because I think awards make a huge difference to a writer at the beginning of (his) career. At my point in life, awards are like icing on the cake.

'Egypt was my writing school'

Egypt, the cradle of many an ancient civilization, has attracted writers for time immemorial.

From Lawrence Durrell, who forsook the 'giant pin-table of inhibitions and restrictive legislation and ignoble, silly defences against feeling' that was England to demolish his critics with the Alexandria Quartet, to Agatha Christie, who followed her archaeologist husband there and soaked in all the inspiration the country offered, writers have rediscovered themselves in this antique land. It was, therefore, not surprising that the Gift of the Nile should have been on Amitav Ghosh's radar when he set out to become a writer.

Ghosh, who went to St Stephen's College, Delhi and thereon to Oxford where he read anthropology, travelled to Egypt on work related to his degree. Since then, he has returned there several times. He considers his experiences in Egypt as most formative in honing his craft.

How did you end up working in Egypt and how did the experience contribute to your writing?

When I finished college, I wanted to travel.

In those days, if you were a young Indian, it was impossible to get a visa. The only way you could travel then was through academics. I got a scholarship to go to Oxford. And while I was there I decided I wanted to travel to north Africa, and then Egypt, so I started learning Arabic. And later, for a book I wrote about Egypt, I learned another very obscure language called Judeo-Arabic, which is Arabic written in the Hebrew script.

I lived in this little village and it was a completely formative experience for me. I wrote a lot, I read a lot... Egypt was really my writing school.

There's a character from Egypt in River Of Smoke -- the Armenian Zadig Karabedian. Was he inspired by anyone you met?

(Laughs) A very close friend of mine is a very famous painter in Egypt and she is Armenian, in fact. The Armenian community has a long history in Egypt, going back to the Mamluk kingdoms. These were slave dynasties and a lot of the slaves were brought from Armenia, and they in turn brought their families and settled them.

This character is partly founded on a real character.

There are these great churches in Old Cairo with wonderful Coptic icons, but they were painted by an Armenian painter and his name was Orhan Karabedian. My character belongs to the same family.

While in Egypt, did you ever meet Naguib Mahfouz, the country's only Nobel laureate?

No, I never met Mahfouz but I know several Egyptian writers. Egypt has a rich literary tradition and I must say I am one of the very few non-Arab writers who is quite familiar with Arabic literature and, I would say, much influenced by it.

'Konkona Sen Sharma is the greatest Indian actress of all time'

What does a great novelist read? Does he go to the movies? How does he divide work and family? These are perhaps not questions that every writer likes to answer, but Ghosh takes them on with great patience and poise.

The bespectacled, snowy-haired writer, who turns 55 in July, lives in New York with his wife Deborah Baker, a biographer who has authored three books including A Blue Hand -- The Beats In India (Penguin, 2008) about the Beat poet Allen Ginsberg's little-known journey to India, and The Convert -- A Tale Of Exile And Extremism (Penguin, 2011), about Maryam Jameelah (formerly Margaret Marcus), a young Jewish American woman who converted to Islam and exiled herself to Pakistan.

Her first book In Extremis: The Life Of Laura Riding (Grove Press, 1993) was short-listed for the 1994 Pulitzer Prize in Biography. Ghosh and Baker have two children -- Leela, 20, and Nayan, 18.

Ghosh began the River Of Smoke tour in Kolkata by dedicating the book to his mother Anjali Ghosh on her eightieth birthday.

Which Indian authors are on your reading list?

Recently I was sent Jerry Pinto's new (unpublished) manuscript Em And The Big Hoom. It's an unusual and powerful book. I also very much enjoy reading the work of Anjum Hasan, an excellent young writer.

Amitabha Bagchi is also someone I like reading very much. I also liked Chetan Bhagat's first book -- I think he has a lot of talent and I hope that the urge to write bestsellers doesn't interfere with it.

Have you considered adapting your books to cinema?

I'm open to it. I receive offers all the time. Several major filmmakers are interested in Sea Of Poppies.

Have you watched any of the new Indian movies?

I watch a lot of movies on my plane journeys. I liked Peepli [Live] a lot. I really liked Luck By Chance -- it was a terrific movie. Some friends of mine think that Konkona Sen Sharma is the greatest Indian actress of all time. And I think it's true. It's wonderful to see how she's maturing.

Irrfan is also an outstanding actor. Both Irrfan and Konkona are technically accomplished. In the past, with Dharmendra too, there were occasionally marvellous performances because he was able to be himself. But the challenge in acting is to be someone other than yourself -- and that is what both Irrfan and Konkona do so well.

I saw this amazing series on HBO in America (In Treatment) that Irrfan was in. I don't know if it is widely seen here. It calls for very technically skilled acting. It's got Gabriel Byrne, who is a superb actor, and Irrfan had a long set of appearances in which he plays a Bengali doctor. I must say it was an absolutely bravura performance. It was astonishing to watch.

Your wife has a different kind of interest in people's journeys. How does it work, having two writers in the family?

(Chuckles heartily) What can I say? My wife is a non-fiction writer, I'm a fiction writer, but essentially we come from the same world. Even though she's American and I'm Indian, we're both people from the literary world and have a powerful language in common.

We talk about what we read and but in as much as getting involved in each others' work, that we don't do. Suppose two bankers were married to each other and they lived in the same house, one is not going to run the other person's business!

River Of Smoke is dedicated to your mother. Did she shape the writer in you?

My mother was an avid reader and that rubbed off on me, somewhat. In a way she was also an aspirational reader. She would push herself to read things that she thought she should read -- the great classics and so on. That made me a more ambitious reader than I would have been at an early age.