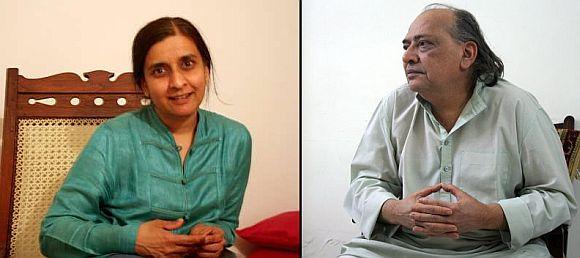

Sheela Bhatt in Ahmedabad

Ahmedabad witnessed some of the most gruesome incidents during the communal riots that rocked Gujarat in 2002. Rediff.com's Sheela Bhatt travelled to Ahmedabad to get to know more about the ethos of the city, which has seen it all in its 600-year-old history

Ahmedabad today drives the hopes of a modern Gujarat. But its underbelly the 600-year-old city, founded by Sultan Ahmed Shah in 1411, harbours prejudices; it carries the burden of numerous riots, communal tensions and political divides that belittles human beings.

In their book From Royal City to Megacity, Achyut Yagnik and Suchitra Sheth narrate how Ahmedabad intersects with history and dominates with dissent, and how tradition here has been transformed by innovation.

In 2002, Ahmedabad saw gruesome communal riots, which claimed the lives of over 400 people on February 27-28 and March 1 in just small area of the city. In fact, in south Gujarat, Saurashtra and Kutch there was no trace of communal tension. It was Ahmedabad that showed its dark and wily side. Ten years since the riots that erupted following the burning of the Sabarmati Express in which 59 Hindus were killed, Ahmedabad has seen only faint attempts to bridge the communal divide.

Yagnik, who leads SETU: Centre for Social Knowledge and Action, a social organisation working among the vulnerable communities in western India, and Sheth, a National Institute of Design graduate who teaches at CEPT university in Ahmedabad, interacted with rediff.com's Sheela Bhatt and in a very subtle and delicate way unravel the beauty of the city as well as the distressing aspects of the city.

Suchitra, before you started researching on the book on Ahmedabad and then while penning it, has there been any difference in your perception?

Perhaps the inter-linkages between many things are clearer now. The economy, architecture and the social setup and the way the present is; perhaps my understanding of how Ahmedabad has come to be is a little sharper and clearer -- that the past informs the present.

'I miss Ahmedabad's lively cultural adda'

Image: The cover of Achyut Yagnik and Suchitra Sheth's book From Royal City to MegacityIn the 600-year history of Ahmedabad, which are the most important phases that have changed the city?

Yagnik: I think the foundation itself is very important. Another important aspect about the city that you find is in the monument built in every century. They are not monuments in that sense of the term, but living entities. Take, for example, the first big mosque was the Jami mosque near Teen Darwaza. Even today, people go there and worship. It is a living mosque, place of continuous worship.

And, then there is the Gandhi ashram, which was established in the second decade of the 20th century by the Mahatma himself. You find people from all over the world visiting here.

So, all 600 years are still alive here. I think one serious problem is concerning the Sabarmati river, which is the heart of the city and is being enclosed by the state government. They have a river-front project.

Also, take, for example, the Kankaria lake. Now, you have to pay for visiting it. They have turned Kankaria into a gated lake. I feel the pinch more than many other people in Ahmedabad because as a boy, I passed by through the Kankaria lake daily.

Sometimes when I see the expanding city I do not feel like I belong to it. My association is with the walled city. Today, I miss a lively cultural adda (hangout). In that sense, the cultural life in Ahmedabad has deteriorated.

Now what you find, especially after 1980, is the politics of culture. The Bharatiya Janata Party, the party ruling since last many years, has started using religion for political purposes. They are using culture for political acts. And that is why you don't find that kind of lively cultural adda discussion any more.

What is your analysis of Ahmedabad?

Yagnik: Please note that the first words in the introduction of our book are that this is a biography of Ahmedabad. By biography we mean that it is a living entity. We don't want to have it converted into a so-called museum. We want a living entity. So when I go to Manek Chowk or when I go to the old city, I remember what happened in the city 40 years ago -- the paths I walked.

...

'It has a provincial yet cosmopolitan identity'

Image: The mill owners' house in Ahmedabad by Le CorbusierDescribe the beauty of Ahmedabad

Suchitra: As I come from a design background, I cannot help but notice the architecture. It is extremely rich and vibrant. Besides its fine medieval architecture, the city has also been home to modern buildings. So it is probably the only city outside of France, which has four Le Corbusier buildings. It has a building by Louis Kahn.

It is informed by modernist architecture, showing you that the city was open to many new ideas at every stage. Whether it is textile or architecture, it has been reaching out to spaces outside of itself. Of course, it wears the garb of a mercantile attitude.

It is a Gujarati city, no doubt about it. But it does not insist on you becoming Gujarati.

Is it?

Yagnik: It has a provincial identity. Simultaneously, it also has a cosmopolitan identity. That's because here you find very well-known artists, architects and designers -- they came from outside and contributed here.

Suchitra: The other thing that you have to remember is that the most beautiful jali -- which is in Siddi Saiyad jail -- was built by an Ethiopian general. The African immigrant's finest contribution is a symbol of the city.

Yagnik: This is not only the contribution of the Western people, this is contribution by the African people.

...

'At every turn of the century, the city has witnessed a problematic period'

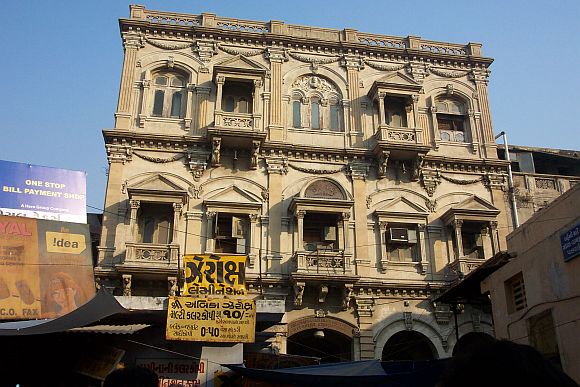

Image: A file photograph of Ahmedabad's walled cityI think no Indian town or city will have this kind of amalgamation of many cultures.

Yagnik: Very few. But I think another interesting aspect about this city is that it is older than all the important cities -- Kolkata, Chennai and Mumbai. Even in the subcontinent, very few cities -- Delhi, Lahore, Mathura, Kashi -- are older than Ahmedabad. And people hardly realise that when they move around, that they are moving in a medieval cum modern city.

Suchitra: And it has outlived its contemporaries. The other cities, which were built at the same time as Ahmedabad, have either remained small towns or have died out.

Yagnik: Take for example, Vijayanagara (in northern Karnataka) was a great city. Now you hardly find it.

I asked you about the major trends of the city in last 600 years.

Achyut: If you look back then you realise that in the past 400 years out of 600, at every turn of the century, the city has witnessed a problematic period. Take, for example, during the beginning of the 18th century because of the Maratha plunder and exploitation, the city passed through troubled times. It continued in the next century also. In the 20th century, the city suffered from great famine and then plague.

Then in the beginning of the 21st century, an earthquake shook the city. And in 2002, it witnessed riots. But this city I think has the capacity to come out of adversities. That is the greatness of this city and that is why we hope that within no time the city will re-emerge and become a very important place.

...

'Unlike Mumbai, Ahmedabad was not planned by colonial masters'

Suchitra: It is always the residents of the city and not outsiders who pull it out. Gandhi came here, lived in the city and transformed it in his own way. When the Marathas plundered it, the nagar sheths bought off the plunderers and saved the city. It was Ranchodlal Chotalal who brought in the textile mills and built the city's economy. So at each point there is somebody from within who seems to emerge and take the story to the next level.

Yagnik: Mumbai (then Bombay) in contrast was a planned city. I am talking about downtown Mumbai. It was planned by the colonial masters. Ahmedabad was not planned by colonial masters but by the city's elite in the late 19th century. If you compare it with Mumbai, you realise the importance of Ahmedabad.

The elite, in the 19th century, were always interested in the development of the city. And they modernised the city as well. Now if we compare the late 19th century with the present period, the late 20th century and the early 21st century, we find that the city elite is not interested in developing the city. It is those who are in power who are trying to leave their imprint. And that is why you find a nexus between builders and politicians. So a person could be a politician by day and a builder by night. And that nexus decides the city's fate. And that, I think, is problematic in India.

...

'Ahmedabad is a casteist city'

When most Indians think of Ahmedabad, they identify it with communal riots and Chief Minister Narendra Modi. How do you see these characteristics? Is it all right to see Ahmedabad in this light?

Suchitra: I think it is useful to see the communal aspect of the city in the context of the many kinds of intolerances that also go along with its inclusive characteristics.

For instance, there have been vicious and violent anti-caste, anti-Dalit violence. So it does not necessarily only take the form of anti-Muslim. As much as Muslims are ghettoised, Dalits too are targeted. They cannot interact freely with all castes.

Ahmedabad is a casteist city. And it's a three-way divide -- economic, caste-based and communal.

The feeling of insecurity is as much amongst Dalits as it is in Muslims. Of course, Muslims have a greater sense of insecurity and there are the grave problems in their inclusion into the fabric of Ahmedabadi society.

Frankly speaking, when I meet Dalits in Uttar Pradesh, Bihar or somewhere else, I still find Dalits in Ahmedabad more confident and I find them moving forward.

Yagnik: That is because there is a sizable Dalit middle class which grew because of the textile industry here. The middle class is very powerful in Gujarat. Though they (Dalits) were textile workers, they understood the importance of education.

So after 1950, you find emergence of educated Dalits. And then most of them got jobs in the mid-century through government quota. If compared to Ahmedabad, you hardly find this kind of powerful Dalit middle-class in many other cities of India.

I would say it is the same for Muslims. They are different, if compared, to the rest of India.

Yagnik: Not very. If you assess the working classes, then you realise the pathetic condition of Muslims. But what is important to note here is that some sections of Muslims are characteristically mercantile communities. For example, the Bohras, who have been traders since centuries, are comparatively well-off.

...

'Despite the communal violence, economic boycott of Muslims was unsuccessful'

Despite the caste and communal divide, how do you see the uninterrupted economic growth and expansion of Ahmedabad?

Yagnik: Right from the day Ahmedabad was founded it inherited the mercantile ethos of Gujarat. Khambhat (formerly known as Cambay) in Anand district of Gujarat and the Gateway of India in Mumbai were very close. Similarly, Ahmedabad was on the main route from Khambhat to Delhi, and northwards. Ahmedabad was on the intersection of what we call the silk route and the spice route. Entrepreneurship is in the blood of Ahmedabadis.

Suchitra: Despite the communal violence, the economic boycott of Muslims was unsuccessful. They continued to do business, but at a price. There may be economic progress but this does not mean there is equitable economic progress, that everybody has had a share in it. There are some who have been dispossessed and marginalised.

Yagnik: The informal sector is very powerful and is the driving force of the city.

Suchitra: Like the river front project. You will dispossess all the communities living along the riverfront who are making a living out of it -- this is the informal sector -- to beautify and make highways and six-lane roads. Who's paying the price for it?

...

'People have allowed Ahmedabad to be geographically and socially divided'

Why are Hindus and Muslims so divided in Ahmedabad? The divide is not as much in Baroda, Surat, Bhavnagar or Rajkot. I don't think Juhapura (where Muslims live) and Vejalpur (where Hindus live) will ever merge.

Suchitra: That is why they refer to them as borders. How do I put it in order to make sense? They have been divided socially. They don't interact socially. This is so also at the level of education. They go to different schools and the kind of sense of insecurity that people have, makes them keep to their own areas.

Nobody has taken proactive steps to set it right. There is a complete absence of any initiative on that front. The city has become divided and the people have allowed it to be geographically and socially divided. I am not competent to comment on why the other cities are not like this or less like this. Surat and Baroda? I don't think they are less divided. Baroda is as communal. Bhavnagar is a tiny town though there is segregation there too; though I don't think you can really compare it with Ahmedabad.

Yagnik: Right from 1969 Ahmedabad has witnessed some of the biggest communal riots. In 1981 and 1985, we saw the anti-Dalit riots. Then riots erupted in 1987, 1990, 1992 and 2002. So we have gone through a series of riots. That is why you find a great sense of insecurity among Muslims.

Suchitra: You will find many families whose shop and house have been burnt again and again.

Yagnik: This kind of social division was very much there when Gandhi arrived. But Gandhians were conscious. They tried to resolve it too.

Suchitra: Groups like Shanti Sena were created to respond proactively to stop this division and improve relations between communities.

Yagnik: After independence, you will find lesser and lesser initiatives for communal harmony, even for equity and justice. Very few people were aware. Very few people were proactive. And that is why we are in such a situation.

...

'In ordinary home conversations, money is at centre-point'

Suchitra, you came to study in NID in 1981. How do you look back?

You must remember that I came here from Kolkata (then Calcutta), which was a big city. And I came here to a town where everything closed at 5 pm and there were only three restaurants. The western side of the city was dead; I was a product of modern Ahmedabad. That is where I lived and interacted. I was surrounded by modernism.

My own college is unrecognisable in so many ways. For instance, if you wanted to go to the museum, you say so to the auto-rickshaw driver as back then the Sanskar Kendra was the landmark for NID. Today nobody will know if you say museum; you have to say NID if you want to go to the museum! It's become that kind of a reversal.

Of course, the Sunday market has changed, the river has got transformed -- everything has changed. But I tend not to be nostalgic about Manek Chowk or lament about how it has changed because I enjoy the terms on which change takes place. And how things change is of interest to me. The fact that it changes is not a big point of sorrow for me. So I am amazed how in 30 years this place has changed -- from what I used to think of as a one-horse town into a highly vibrant place. Of course, the way it has gone is not ideal, far from it.

Is it true that Ahmedabad is a money-minded city?

Suchitra: Of course it is.

What about relationships? Family life?

Suchitra: I think there is money there also. In ordinary home conversations money is at centre-point. But money is not discussed as if it is not a good thing. It is so natural for people to talk about money. It's like breathing in and out. I don't think they realise it even. But of course, one's status is connected to money. I find it unfortunate that such an intelligently vibrant community can be so single-minded sometimes to view everything along the axis of money; I still feel amazed by it, even after living here for more than half my life.

Click on NEXT to go further...

article