| « Back to article | Print this article |

'We pay bribes at every step of our daily lives'

On a chilly January morning, Rediff.com's Sheela Bhatt and Sharat Pradhan traveled off National Highway 24 to probe rustic Indian minds on corruption, weeks ahead of the election in Uttar Pradesh.

Welcome to Paharpur near Malhipur, which is near Bakshi Ka Talab town, just 27 kilometres away from the Uttar Pradesh capital, Lucknow.

In the bazaar, we meet a middle-aged journalist, 'Panditji' (a common honorific to Brahmins in this part of the country). He contributes to a Hindi daily newspaper on a monthly salary of Rs 3,000.

In the few hours we spend in the dusty farmlands, we encounter nothing but tales about corruption, corruption and more corruption.

"Upper castes these days don't like to slog in farms," says 'Panditji'. "I am a farmer, but I have given away my farms to the lower castes. They plough the land and grow wheat. I get a 50 per cent share."

While pointing out that outsourcing of farms is a lucrative business, 'Panditji' explains how it works. The village is not far from Lucknow. In UP, he says, the politicians and bureaucrats are the wealthiest people around. Both invest heavily in land, particularly in and around Lucknow because it is the only city that sees development in India's most populous state.

"A BSP (the Bahujan Samaj Party, which rules UP) politician owns 400 bighas of land near Lucknow. He acquired all that during his tenure as a cabinet minister in the Mayawati government. We know many bureaucrats who own hundreds of acres of land bought with money that they earn as bribes," alleges 'Panditji'.

"We deal in their land and we get them in contact with lower castes farmers who manage their farms," adds 'Panditji'. "We get a commission from the deal."

'Panditji' has bought an apartment in Lucknow from what he has earned from farming and such transactions.

Please click NEXT to read further...

'Casteism will take a few more generations for it to go away'

'Panditji' introduces us to Santosh Kumar, the elected pradhan (head) of the village panchayat in Paharpur.

Kumar belongs to the 'Pasi' (Dalit) community and owns a tiny store selling readymade garments. He proudly proclaims, "I am a Pasi. I am an intermediate (corresponding to the present Class 12) fail."

When asked "When will you forget your caste?" he smiles. "How can we forget our caste when we start our day in the village school with a daily morning prayer -- 'Jis desh jaat main janam liya, balidan usi per ho jaye (Sacrifice your life for the country and caste of your birth), says Kumar."

Casteism is on the decline, he feels, "but it will take a few more generations for it to go away."

Asked if inter-caste marriages -- between the 'Chamars' and 'Yadavs' or 'Kurmis' and 'Pasis' -- are possible in his village, he says, "We are not worried about our own people. We are worried about our neighbours. We eat together in bazaars, but we don't go to each other's houses to share food, yet."

Asked if governance has improved, and corruption is less pronounced than during previous state administrations, he gets provoked even before we can complete our questions.

"Corruption? I have to give bribes at every step and at every government office. I was compelled to give a bribe of Rs 3.5 lakhs (Rs 350,000) to get my nephew a constable's job in the UP police. To get sanction for getting a Rs 2 lakh (Rs 200,000) job carried out under MNREGA (the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act), I have to shell out a kickback of 25 per cent to the BDO (Block Development Officer)."

"If I want to sell my wheat or paddy to the government under the minimum support price scheme, I have to bribe the concerned official who will find a hundred faults with my produce if I resist his demand for a bribe," adds Kumar.

"The government has issued a long list of criteria to buy farm produce directly from farmers at a fixed rate," he says. "That list is just for corruption because in India nobody can produce at the standard fixed by the government."

"Bribery is a part and parcel of our daily lives, so much so that right from the time of birth until death, we have to keep giving out bribes," says the village pradhan.

"Take the case of the government scheme for an incentive of Rs 1,400 to pregnant women who agree to get their babies delivered in government health centres or hospitals to encourage safe deliveries. A payment of Rs 600 is also officially meant for the midwife," Kumar adds.

"While taking away her rightful share," he alleges, she (the midwife) plays the middleman by asking the mother to pay some underhand money to the nurse as well as the doctor, which is generally Rs 1,000. What is eventually left for the poor beneficiary is nothing more than Rs 400."

"Every criminal pays bribes to the police," Kumar alleges. "Even for getting a date in a magistrate's court, one has to pay speed money. Be it a legitimate arrest or the case of a falsely implicated person, a bribe is a must for the police."

"We have to pay money to get a birth certificate, jati pramanpatra (caste certificate) and even a death certificate as well as to get a post-mortem report. The rate is upwards of Rs 800, which an advocate demands for procuring a caste certificate."

Please click NEXT to read further...

'Standards of education is hopeless in the villages of UP'

"We have six schools in the village," says Santosh Kumar. "But the senior teacher, who earns a monthly salary ranging between Rs 25,000 and Rs 35,000, hardly cares to carry out his/her duty."

"Those teachers who attend schools, openly sleep in the classrooms," the village pradhan claims. "Most of the teachers, who belong to the upper castes, have their homes in the city. In the case of women teachers, their husbands usually earn well. These teachers ignore the schools. They are not punished even after our written complaints because their husbands see that no action is taken."

"Even ministers call up to ensure that errant teachers are not punished or transferred," he alleges. "Needless to say, the standards of education ends up as the most hopeless in the villages of UP."

In the absence of functional government schools, parents who can afford the fees, choose to send their children to private schools where they must pay between Rs 350 and Rs 500 per month.

Often those students are enrolled simultaneously in government schools. And with the connivance of the government school teacher and the local gram pradhan, these students can avail of the scholarships and other facilities flowing into government institutions.

Santosh Kumar says believes the quality of education in most private schools is also deplorable.

In his village, he claims a girl who studied till Class 8 is employed as a teacher at a private school!

"Nobody goes to a government school for education," he says. "They go for the stipend of Rs 300 per student and the mid-day meal."

"There are never any complaints about the quality of education to the education department," he adds. "Instead, complaints are made about the late payment of stipend and the poor quality of the mid-day meal."

The proceeds from the mid-day meal, he alleges, is conveniently shared between the teacher and village pradhan. While the bill for the scheme is created for 200 students, only 100 students may actually eat the mid-day meal.

The officially allocated meal or money in lieu is shared by the teacher and the pradhan, who has to maintain the paperwork for the mid-day meal scheme.

Please click NEXT to read further...

'We don't want MNREGA. It is ruining our lives'

"Hum goos nahi lete, sirf beimani karte hai! (We don't take bribes; we just do dishonest things)," explains Hariram Tiwari, a former pradhan from the neighbouring village.

"To get a project approved under MNREGA," says Tiwari, "we beg, borrow or steal to give bribes to government departments. But we never take bribes for work we do or from the villagers."

"However, we do fake labour jobs under the scheme because our villagers are just not ready to work hard," he confesses. "If a small pond exists, we will do a little job around it and show it as a new job."

Asked if it means that not much has changed in the village, Santosh Kumar says, "MNREGA has changed everything. It has created a corrupt society. People just don't want to work. They get registered in MNREGA and take Rs 120 per day. Work for one or two hours and go home."

"MNREGA ensures 100 days of work in a year. Out of the Rs 120 they spend half of it on alcohol and chicken."

"To get a project under MNREGA, we have to bribe. But I assure you as a pradhan I never take bribes," he says. "Most villagers give bribes, I don't take it."

Santosh Kumar alleges the villagers had to bribe the BDO to get fishing rights to the village pond. When the 'auditor' inspects projects under MNREGA, he claims this official takes a bribe of Rs 5,000 per visit.

"The villagers are poorer due to MNREGA. Since money goes to the villagers directly, they don't listen to me. They don't work nor are we are in a position to create any assets with MNREGA," says Kumar.

"The money goes waste," he adds. "Most of the funds that were coming to the village gram sabha before are now coming largely through MNREGA. We don't want MNREGA. It is ruining our lives."

Points out Tiwari, "If the government wants to give money to villages through MNREGA, then you need to have a fool-proof system to protect the money."

Please click NEXT to read further...

'Upper caste cleaners outsource jobs to the Dalits'

Asked why the village is so dirty and full of garbage, Santosh Kumar says, "The government has appointed safai karmacharis (cleaners) in every village. Each earns Rs 10,000 per month. In our village, we get two cleaners. But this post is not under 'reservation.' It is filled up by the upper castes."

"The upper caste safai karmcharis don't do cleaning jobs. They have never done it traditionally," he explains. "They outsource the job to lower caste Dalits, the Mehtars. They pay them Rs 6,000 and pocket Rs 4,000 without working a single day."

"The Mehtars," he says, "work for daily wages on farms. They don't do the cleaning because they are not employed officially and we can't take them to task because they are not formal employees," says Kumar, not explaining why he cannot penalise the upper caste safai karamcharis for not keeping the village clean.

Please click NEXT to read further...

'Rahul Gandhi says he gave Kisan credit cards to farmers, but it's of no use'

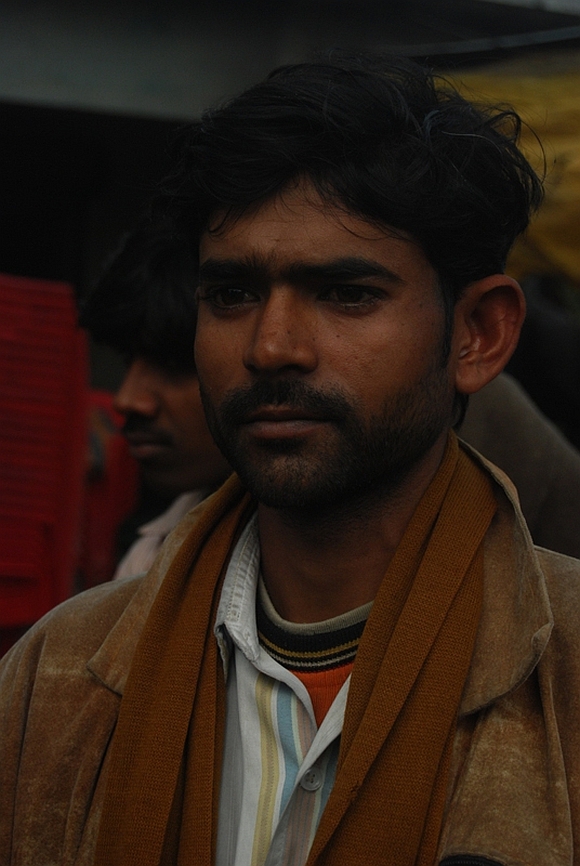

On hearing the discussion on corruption, Avdhesh Kumar Rawat jumps in and says "(Congress General Secretary) Rahul Gandhi says he gave Kisan credit cards to farmers in UP. It is of no use."

"For the last three months," says Rawat, "I visit the local cooperative to get my quota of urea, but the officer never comes. The season has passed, but I never got any fertiliser through the credit card. In the open market it will cost me 40 per cent more."

"The officers don't come because they are selling off fertiliser stocks in the blackmarket," he alleges. "I am a Dalit and it is our (the ruling Bahujan Samaj Party is perceived as a Dalit party) government, but I am still not able to get fertiliser."

Adds Rawat, "Had the officers of the fertiliser cooperative been Dalit they would have understood our issues. Since the day the BSP became a Sarvajan party (when the BSP accepted Brahmins and other castes into its fold) we have lost out! Since then, work of the Dalits is not being done."

Rajapur village adjoins Paharpur.

Ram Kripal Yadav, a resident of Rajapur, says, "For extremely poor families the government gives a red ration card. Others below the poverty line get a white ration card. People have to pay bribes to get any ration card. Without paying bribes nothing moves in our lives. Neither (Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister and BSP supremo) Mayawati nor (Samajwadi Party President) Mulayam Singh can make any difference to our lives."

Please click NEXT to read further...

A shocking glimpse of corruption and threats

Suresh Kumar, his neighbour, provides a deeper glimpse of corruption.

He is a Pasi with a large family including two married brothers and their 11 children. The three brothers own five bighas of land.

A Yadav family from the neighbouring village allegedly usurped their land by paying a bribe to a deputy district officer.

Suresh Kumar's family wants the land that has been with them for many generations. They are being threatened by the Yadav family that if they demand their land back, Suresh Kumar and his brothers would be sent to jail by influencing the local police -- by bribing them, obviously.

A worried Suresh Kumar gave a Rs 50,000 bribe to the revenue officer so that he could get the land transferred back in his name. But that officer took the money without obliging him. Suresh Kumar has been running from pillar to post with photocopies of his property papers, but to no avail.

While his neighbour and fellow Dalit Rawat is in a mood to rebel for not getting his urea on time, Suresh Kumar is unlikely to shift his 'Dalit vote' from the BSP to Mulayam Singh Yadav's Samajwadi Party. He is scared.

Some of his relatives are in the mood though to cast an anti-BSP vote to protest the high levels of corruption and the failure of governance during BSP rule.

"You may ask us about our voting preference, but that we can't share it," says Rawat. "You can live with us for one month but no one will tell you whom they will vote for."

Please click NEXT to read further...