Compulsory retirement is part of a half-yearly exercise now for cases where government wants to weed out officers, but without taking the disciplinary proceedings route.

The recent compulsory retirement of Rinku Dagga from service conveys a message of penalty, but she is not the first officer whose services have been terminated in this manner since 2020 when the rules governing government officers were expanded. She is one of 88.

Dagga, an Indian Administrative Service officer, and her husband, Sanjeev Khirwar (also an IAS officer), had made headlines last year for reportedly getting sportspersons to finish training early so that they could walk their dog in a stadium in New Delhi.

While Khirwar was transferred to Ladakh, Dagga, who was earlier sent to Arunachal Pradesh, has now been compulsorily retired.

The new rules for such compulsory retirement clarify that these orders are not necessarily offered 'as a penalty under CCS (CCA) [Central Civil Services (Classification, Control and Appeal)] Rules, 1965 (which) is distinct from these provisions'.

Dagga's service has been terminated under Fundamental Rules (or FR) 56(j), Rule 48 of Central Civil Services (CCS) Pension Rules, 1972, in 'public interest'.

So, unless the office concerned, which in this case is the Department of Personnel and Training, decides otherwise, it is considered a termination and not a penalty.

This action is the toughest that the government could have taken since the rules governing the protection of service of state government officials in India are stringent.

Dagga is a 1994 batch Arunachal Pradesh-Goa-Mizoram and Union Territory (AGMUT) cadre officer.

The compulsory retirement is part of a half-yearly exercise nowadays, done for cases where the government wants to get rid of officers, but without taking the disciplinary proceedings route.

As a review by the Department of Personnel and Training a few years ago noted, a Central Vigilance Commission manual prescribes that disciplinary proceedings have 'a realistic time schedule of nearly 25 months for completion'.

The compulsory retirement route offers a way out.

Every six months, departments can conduct the weeding out exercise for officers, but after the officer 'attains the age of 50/55 years or completes 30 years of service, whichever occurs earlier'. Dagga is 50-plus.

The section used against Dagga, as reported to Parliament, notes, 'The objective of the review process under the FR 56(j) (or) similar provisions is to bring efficiency and to strengthen the administrative machinery'.

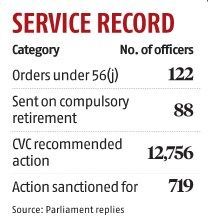

As the table (service record) shows, in the three-year period from April 2020 to March 2023, this section has been applied on 122 officers.

What do the sections say?

There are two provisions in the Fundamental Rules that guide how the government can deal with the removal of officers from the central civil services.

There is Section FR 56 (k), which allows an employee to retire from service voluntarily with all pension benefits before attaining the age of retirement.

And, there is Section FR 56 (j), which notes that 'the appropriate authority has the absolute right to retire, if it is necessary to do so in public interest, any government employee'.

The caveat is that FR-56 (j) and the related All India Services (Discipline and Appeal) Rules, 1969, for putting out an officer to pasture apply to those officer whose 'performance has been reviewed and found unsatisfactory'. The operative words are 'public interest'.

The National Democratic Alliance government has tried to revise these stiff rules to ensure there are at least specific timelines in the procedures related to disciplinary proceedings, according to a Parliament reply.

Yet, as a former government employee pointed out, "Asking an officer to leave while keeping their pension intact does not mean much."

The pension gets reduced to two-thirds only if the government, after consultation with the Union Public Service Commission, decides that 'the retirement benefits shall be paid at such reduced scales as may not be less than two-thirds of the retirement benefits under FR 18 and 19'.

Feature Presentation: Aslam Hunani/Rediff.com

© 2025

© 2025