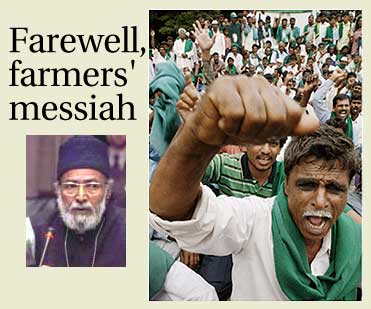

The greatest legacy that the erudite Professor M D Nanjundaswamy gave the people of Karnataka is the ubiquitous green scarf.

You see them everywhere, farmers wearing green scarves: on the streets of the cities, ploughing fields in the remotest villages, occasionally stopping traffic on the highways in protest against agricultural policies or water management.

Even if the farmers movement never really took off as a third, or even a fourth force, in Karnataka politics, the Kannadiga farmer now has a simple, easily wearable symbol that he can flaunt wherever he goes.

Ever since Nanjundaswamy started the farmers movement in Karnataka two decades ago, the dhoti-clad villager sporting a simple green scarf around his neck has become a figure that commands respect and recognition.

He has also become a symbol of the farmer who is no longer willing to either exploited or taken for granted. He is, instead, perceived as the rather menacing man of action, who cannot be stamped down by everyone, right from the exploiting MNC to the supercilious city slicker.

The farmers lobby was, at least numerically, the largest pressure group in Karnataka, for many years. It started off as a sugarcane growers movement with a power base in Shimoga, and spread slowly to the northern parts of the state. The issues that it championed grew accordingly.

The origin of the farmers movement can be traced back to a small growers federation set up in the Hassan and Chikmagalur districts of Karnataka in 1968. However, the Raitha Sangha was officially launched a dozen years later. The ham-handed manner in which the then chief minister R Gundu Rao handled an uprising of farmers in the Navalgund and Nargund taluks of the Malaprabha project area in Dharwar in 1980 helped the Raitha Sangha consolidate its position as a state-wide body. Two farmers who were killed in police firing at that time became the martyrs of the farmers movement and the Raitha Sangha became the most vocal and focal forum of the farmers lobby.

At first, this forum was strictly apolitical. Then, in the early 1980s, a political wing of the Raitha Sangha that called itself the Kannada Desha Party, was born. Nanjundaswamy was its president and Babagouda Patil was its secretary. The party contested the assembly election for the first time in 1989, and was generally expected to emerge as a serious third force, after the Congress and the then united Janata Party. Instead, it fared very badly, and continued to do similarly in all future state-wide elections after that.

This, despite the fact that Nanjundaswamy and his friends always claimed credit for having the Janata Party government of S R Bommai dismissed in 1989. Right up to the end, Nanjundaswamy was always hopeful of the farmers movement in Karnataka gaining political power sooner or later. When this correspondent pointed out to him, many times, that farmers movement had never come to power in Karnataka, he would always reply: "That is because they were not organized. They are bad precedents, not reliable ones. The movement in Karnataka is different. Our campaign is based on an understanding of the existing political parties in the state."

Nanjundaswamy was, in many ways, the antithesis of what one would expect a farmers leader to be. He was a rather frail, grey-haired, bearded, bespectacled man who looked and spoke as if he was either an academecian of some sort, or a scientist working in the labs of the very MNCs he fought tooth and nail.

He spoke flawless English, and spoke in the erudite and almost pedantic manner of an economic analyst, and never used the more rustic idiom of the man of the soil.

Over the past two decades, this correspondent met him innumerable times, and even organized a live chat online between him and rediff.com readers two years ago. It was Nanjundaswamy's first interaction with this medium, and he was most intrigued by it. Interestingly, he handled the flood of questions, very easily.

According to Nanjundaswamy, his organization represented a quarter of the state's farmers, 75 percent of whom own no more than five acres. He always said that the farmers have been victim to under-estimations in production costs down the ages. Their problems, he said, have been compounded by cuts in fertilizer subsidies. All the government's support price mechanisms, he pointed out, were completely outstripped by rising inflation.

All this, he always believed, was no accident. "The government shows a smaller cost of production to help dumping (of imports)," he told me, quite bitterly, on one occasion. "It has been doing so since the British rule days. I see no big change in this scenario."

If there was one criticism I heard leveled against Nanjundaswamy over the years, it was that he actually belonged to the class of the landlords who ruled India rather than to the ranks of the landless, exploited farm labourer. Some of his policies were also criticized as being more pro-landlord than poor peasant. For example, one of his election promises was to lobby for the regularization of farm land encroached upon by farmers.

Nanjundaswamy's critics point out that rich planters were actually the biggest culprits when it came to encroachment! "So, I propose that a farmers' movement led government should then acquire this land encroached upon by rich landlords and planters, and redistribute it amongst the poor," Nanjundaswamy would explain airily.

However, the image that remains most strongly in my mind, after a decade-and-a-half of sporadic interaction with this highly evolved farmers leader, is of the day, over a decade ago, when farmers of the Raitha Sangha attacked the offices of the agricultural giant Cargill, and destroyed a lot of their paperwork, in protest against the MNC's move to get into the seed trade.

It was like a scene straight out of a movie. Dhoti-clad farmers on the rampage, swarming all over the pristine downtown office of an MNC, ripping open cabinets, rubbishing files. News photographers had a field day recording the event for posterity while the American CEO of the firm looked on helplessly.

That was Nanjundaswamy for you. "We prefer direct action, at such times," he remarked placidly, after that event, to this correspondent, the ever-present green scarf wound around his head like a turban. Without him to spearhead the movement, at the approaching assembly election in Karnataka, it seems doubtful that the farmers movement will have any political presence at all.

Photograph: Indranil Mukherjee/AFP/Getty Images

Image: Dominic Xavier

© 2025

© 2025