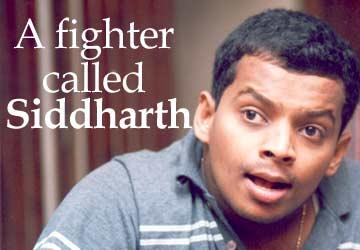

Siddharth G J's mother and father are proud parents. And that's not because of his masters in economics with distinction. The 24-year-old has faced tougher tests, fought bigger bogeys and crossed higher hurdles with his indomitable fighting spirit.

Siddharth has cerebral palsy.

In medical-speak, that means an affliction caused by the cut-off of oxygen to the brain at the time of birth or early infancy. It irreversibly damages the communication between the brain and muscles, resulting in lack of coordination in muscular movements and defects in posture.

In medical-speak, that means an affliction caused by the cut-off of oxygen to the brain at the time of birth or early infancy. It irreversibly damages the communication between the brain and muscles, resulting in lack of coordination in muscular movements and defects in posture.

In real life, it means being considered mentally retarded, being looked down upon, and being refused admission in colleges and jobs despite an outstanding academic record.

Siddharth's battles with fate began early. He had jaundice when he was three days old, and was unconscious for three days. "As he grew, and did not show the usual landmarks in development, we knew there was something wrong. It was an extremely shocking news for us," says his mother Komala.

Some doctors in Bangalore told Komala and her husband Jayakumar that their son was 'mentally retarded.' "We knew from his responses that he was as intelligent as any other child if not more but that was what the doctors said."

Siddharth's early childhood was not the usual one with friends and schoolmates. For eight years, he stayed at home. A neighbour worked with a special school run by the Spastic Society of India, and Siddharth got admission there. "The first thing they taught me was how to use a typewriter. I typed with one finger, and even today, I type with one finger. Except math, I started doing all my school work on my typewriter," says a smiling Sidhharth. His school followed a different syllabus for each student, depending on his/her ability. So, Siddharth was sent to standard II from upper kindergarten.

Sidhharth's father Jayakumar got transferred to Chennai. Siddharth now had to get used to a new school, a new environment and new challenges. "I remember I cried when we left Bangalore," he says.

He studied at Vidyasagar, now a well-known school for spastic children. "It was not as big as it is now," says Siddharth. "I have no words to describe Vidyasagar's role in my son's life," says his mother.

When he finished standard VIII, the school authorities felt Siddharth should go to a regular school. Before Siddharth, they had sent just one other boy to a regular school. "I also feel disabled people should be studying in regular schools because generally other children, and even adults, are not aware of the disabled. The attitude of the public is that the disabled can't do anything. Only when more and more disabled children are integrated into regular schools will society understand us," says Sidhharth.

"Initially, it was very difficult for me. Writing, people, the workload it was difficult to interact; I felt miserable."

In his standard X board exams, Siddharth took assistance to write his answers. But the government sends people who are not proficient in math and science, and "there were times I had to dictate letter by letter," says Siddharth. That did not stop him from scoring 98 percent in his favourite subject, math. He opted for commerce, and in his standard XII board exams, scored 90 percent.

Happily ever after? Far from it, says Siddharth. "Vivekananda College, where I applied, looked at me and refused to look at my academic performance. I was very upset. I asked myself, why are these people not looking at my marks? Why are they looking at my disability?"

Siddharth's father spoke to the Vivekananda College principal, and also his teacher at Vidyasagar, Deepthi Bhatia, who is blind. "I assured the principal that he [Siddharth] would be an asset to the college," says Jayaram..

College for Siddharth was again a different experience. "Many students didn't know how to deal with disabled people like me. It is not that many of them didn't want to make friends with me. They didn't know how to approach me. As I am a shy person, I also couldn't initiate conversation."

Despite "sleeping in most of the classes," Siddharth's brilliance shone. He scored 100 percent in management accountancy and computer science the only one in his batch to do so with an overall 74 percent in Bcom.

Despite "sleeping in most of the classes," Siddharth's brilliance shone. He scored 100 percent in management accountancy and computer science the only one in his batch to do so with an overall 74 percent in Bcom.

Siddharth wanted to do his masters in social work from the prestigious Loyola College. "I was denied admission to the course I wanted: MSW. They decided that I would not be able to do MSW because of my disability. I was angry. How could somebody else decide for me? They refused to listen to my arguments. Luckily, I had also applied for MA in Economics. Though it was disappointing to miss out MSW, I joined the college."

He thought his struggles ended with getting a postgraduate degree with distinction. That was not to be. When he applied for jobs, people did not look at his academic record or ability; they saw only his physical disability. A family friend asked Siddharth to join his public relations agency.

"Ma'am, all those press releases you received from Prism till a month ago were written by me," Siddharth says, smiling. With his first salary, he bought a pair of shoes for his father and gave the rest of the money to his mother.

But Siddharth wanted a job on merit. "I continued applying to several places. All of them called me because of my resume. I used to perform well in the aptitude tests also but the moment they saw me at the interview panel, they would say, 'We will get back to you.'"

"Big companies like Infosys and TCS [Tata Consultancy Services] appeared satisfied with my technical knowledge in economics but they did not get back to me. They don't trust people with disability. This distrust is very, very bad," says a visibly angry Sidhharth.

At a job fair where there was a separate section for the disabled, Siddharth gave an aptitude test for ABN Amro Bank. "They were very co-operative. I passed the test."

At the interview, Siddharth spoke about himself. "They were stunned. On the spot they said you are selected. I felt damn good! They didn't tell me what my job would be but I told them I didn't want a data entry job. I told them I was looking for a research-oriented job. They were very receptive. For the first time, somebody realised my potential."

Surabhi Nikumbha, one of three on the interview panel, says, "We just listened to him [Siddharth], rather his story, for 45 minutes. We just couldn't ask a single question. All three of us were stunned. We didn't even know how to react. It was an amazing experience.

"His academic performance was exceptional, and you should see the way he answered our aptitude test. We were also impressed to find him so independent. He came on his own, did everything on his own. His department tells us that he is excellent in his work. He is an asset to us. We are proud to have him in our organisation."

Today Siddharth G J, officer trainee, ABN Amro Bank, examines import and export documents for compliance with international standards of documentation. "I am enjoying every moment of it. People at ABN Amro trust me wholeheartedly. It is just a beginning for me," says our hero. And he still writes poems. "No, they are not for publishing. They are very, very personal," he says.

"Children like him need only love, affection and encouragement; not sympathy," says his mother.

Photos: Sreeram Selvaraj

Headline image: Rahil Shaikh

© 2025

© 2025