Photographs: Photo credit: Shreewardhan Dhanwatey

Three tigers die in a week under mysterious circumstances; total 32 deaths in two-and-a-half years; all in the forests of Corbett, a showpiece of tiger conservation. Who is targeting the tiger? Kumar Sambhav Shrivastava investigates

It was a hot May evening. Near the south-eastern border of Corbett Tiger Reserve, Gopal was busy lopping off branch after green branch for his cattle to eat at night. His hands moved fast -- a tiger reserve is not the place to be caught alone when night falls.

Just as the 16-year-old boy neared the stream close to Patrani village, a stench overpowered his senses. The disgusting smell was coming from a pile of dry branches. Curious, Gopal peeped under the branches. Belonging to the grazier community of the Himalayas, Van Gujjar, he has grown up on gruesome stories of mountain beasts.

But nothing could have prepared him for what he saw that evening. A rotten, stinking pile of flesh, with patches of black- and-yellow-striped skin, lay before his eyes. Maggots slithered out of the gaping hollow which must have been a tiger’s mouth once. Gopal lost no time in informing the village forest guard about what he just saw.

The guard, in his liquor-induced stupor, could barely comprehend what the boy said. But by next morning, on June 1, word had spread like fire about yet another tiger death near the reserve. This was the third tiger carcass to have been found in Corbett in a week. Two more decomposed tiger bodies had been recovered from around the reserve boundary between May 27 and June 1.

On May 27, a fully decomposed carcass of a three-year-old tigress was recovered from the bushes on the bank of a seasonal river in the Dhela range just inside the boundary of the reserve. The body appeared to have been lying there for five to six days. Just two days later, a half-decomposed body of a fully grown tiger, aged six-seven years, was found near a sot (water body) in Sanwaldeh village in Ampokhra range of Terai West Forest Division.

The spot, though outside the reserve boundary, was hardly seven kilometres from where the first carcass was found. The body seemed to have been decomposing for three-four days.

...

Fight theory

Photographs: Photo credit: Shreewardhan Dhanwatey

Van Gujjars from the settlement where the first tiger carcass was found say the tigers have died after a fight. They talk of hearing the growl of tigers fighting on May 22 evening.

“It seemed the tigers were fighting right behind our huts. We shouted and flashed torches to scare them away. Later, I informed the forest staff on phone about the probable fight between tigers,” says Ghulam Nabi, a Van Gujjar.

The forest staff confirms this. “It was too late in the night when we got the call. We decided to patrol the area for wounded tigers in the morning. For the next three days we patrolled the entire range but could not find the tigers,” says a forest guard. “It seemed the tigers went far away from our range after the fight.”

This does not sound implausible. Tigers are territorial animals and with a density of 9.4 tigers per sq km, territorial fights are common in Corbett. There are, however, certain aspects of the tiger-fight story that make it far from credible. The first carcass was found lying less than 500 metres from a forest check post four days after the so-called fight.

If forest staff had patrolled the area why could they not find the wounded tigress? A conservationist who was present at the site when the carcass was recovered says there were hardly any wound marks visible on the carcass to suggest a fight. Another unanswered question is: if there was a fight, where is the other wounded tiger?

The forest staff, in its defense, suggests the third carcass spotted by Gopal could be of the other tigress. It probably fought with the first one and went towards Patrani and eventually succumbed to wounds.

But it is rare that both tigers die after a fight. Most territorial disputes are settled through posturing or fights. And if the third animal did die after the fight, who hid the carcass under the bushes?

Possibility of human hand behind the deaths?

Photographs: Photo credit: Down to Earth

If it had been rotting there for six days how come guards from the watch tower failed to notice it? The fact that all the three carcasses were found near Van Gujjar settlements led to quick conclusion of the community’s involvement.

“Lightening does not strike at the same spot thrice in a day,” says a visibly perplexed Samir Sinha, who had joined as the director of the Corbett Tiger Reserve in Uttarakhand barely a week before the mysterious deaths. He is sure the tigers have not died a natural death and claims foul-play.

Serial deaths

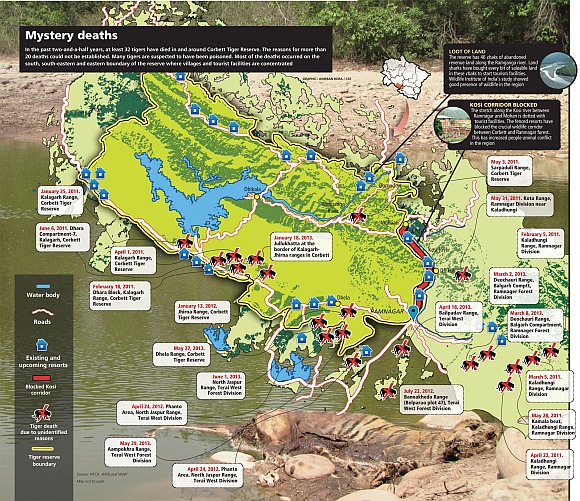

While the number of tigers in the reserve and surrounding forests has increased from 164 in 2008 to 214 in 2010 -- these forests now boast the world’s highest tiger density -- the spate of tiger deaths since the last census has given a dark twist to the much-hyped conservation story of the Corbett. At least 32 tigers have died in Corbett in the past two-and-a-half years.

The forest administration had tried to play down the incidents in the past, saying a few natural deaths every year are not a cause for concern considering the tiger population density in the reserve.

But even the records of the National Tiger Conservation Authority show only 11 of the 32 tigers died of natural reasons or because of poaching. The cause of death of 21 others remains unknown -- the frequency and circumstances of these deaths do not support the natural-death theory (see map).

Most of the suspicious tiger deaths have occurred in those areas of the Corbett and nearby forests that touch the Uttar Pradesh border. Several villagers and communities there depend on forest resources. Tourism is also thriving near these villages. It is a common perception among wildlife lovers that people living close to forest often kill big cats in retaliation following attacks on them and their cattle by tigers.

“The boundaries are porous and human-animal conflicts are common in these areas. Due to extremely poor patrolling by the forest department in these regions, such incidents cannot be averted,” says Tito Joseph of Wildlife Protection Society of India.

It is only after the recent wave of tiger deaths that the Corbett administration has acknowledged the possibility of human hand behind the deaths. But they are not sure who it could be.

...

The case files

Photographs: Utpal Baruah/Reuters

The last case that involved Gopal is the most intriguing. Forest officials found the carcass lying on its back in the North Jaspur range of the Terai Forest Division. This is not a posture a dying tiger would naturally take.

The body was so badly decomposed that it was difficult to ascertain the gender and age of the tiger. Later, it was assumed that it must have been a two-three-year-old tigress. The general sense is that the animal died somewhere else and the carcass was shifted to mislead investigations.

The post-mortems of the tigers have been inconclusive because the bodies were highly decomposed. Samples of a few body parts have been sent to the Central Drug Research Institute in Lucknow and reports are awaited. Circumstantial evidences, however, point towards a strong possibility of poisoning.

For one, all the three tigers were less than seven years of age. The average age of tigers in the wild is 12 years; in Corbett, with a constant struggle for space and prey, it is considered to be 8-10 years. This negates the possibility of natural death.

Secondly, all carcasses were found under trees or bushes near water bodies. “Poison dehydrates the body. When poisoned, animals feel thirsty and tend to go towards water bodies. They also avoid the sun when they start feeling unconscious,” says Bilal Habib, a scientist at the Wildlife Institute of India in Dehradun. There is a strong possibility that the animals ran towards water bodies after being poisoned. The officials also hint at poisoning, albeit hesitantly. “It (poisoning) has not been proven in the post-mortem report. But certainly cannot be ruled out,” says Sinha.

...

Who is the culprit?

Professional poachers have been active in the Corbett reserve in the past few years but they do not seem to be the culprits in these cases. For one, they generally use firearms or traps to kill tigers and not poison, which can render certain body parts useless for sale. Secondly, all body parts of the dead tigers were intact. Why would poachers kill a tiger if not for its body parts? But if not the poachers, who else?

The usual suspects in such cases have been the Van Gujjars. They had been living in the ShivalikMountains near the Corbett Tiger Reserve for over a century. Of late the nomadic graziers have started living in permanent settlements, several of them inside the Corbett. As per official figures, 181 Van Gujjar families live in the reserve and many more in the buffer zone and areas near the reserve boundary.

There have been instances in the past when Van Gujjars killed tigers in retaliation of cattle-lifting. They have reportedly used non-productive cattle as bait and rubbed Nuvan Prostrips, a pesticide easily available in the local markets, over its skin to poison the tiger.

Local media and people in Ramanagar suspect the graziers are behind the recent tiger deaths as their settlements lie within 200 metres of the two spots where carcasses were found. There, however, are several facts that work in graziers’ defense.

It was the Van Gujjars who spotted two of the carcasses and informed the forest department. Besides, there have recently been no confirmed reports of cattle-lifting in the region. “We have been living in harmony with the forests for centuries. We cannot survive if we harm the forests, antagonise the tigers or not cooperate with the forest department,” says Ghulam Nabi.

“Van Gujjars were involved in some such cases in the past but that was long time back. You cannot brand the whole community as tiger killers,” he adds.

...

Who is the culprit?

Photographs: Kamal Kishore/Reuters

Retaliation is a simplistic explanation for the tiger deaths, says K D Kandpal, team leader at the World Wide Fund for Nature office at Kaladhungi near Ramnagar.

“Retaliatory killings used to happen earlier when it was very difficult for villagers to claim compensation for cattle killed by tigers. But since the process has been made simple and smooth, the number of such incidents has come down drastically in the past three-four years,” says Kandpal.

Earlier the government ran a scheme to compensate villagers for cattle-lifting by tigers. Verification of claims under this scheme was complicated and riddled with corruption. Besides, the paltry amount of Rs 12,000 was nowhere close to the market price of a productive buffalo, which is about Rs 50,000. Frustrated, villagers would resort to killing tigers to prevent cattle-liftings.

Few years ago WWF, along with a few local non-profits, started a scheme to compensate the villagers for cattle-liftings. Apart from the government compensation, the WWF scheme provides Rs 5,000 for every buffalo killed by a tiger.

“We process the claims within one week. Verifications done by us are also accepted by the government. This simplifies the compensation process at the government level, too,” says Kandpal. “As villagers can now get at least some money back for their cattle, they immediately report cattle-killings to the WWF and do not kill the tiger.”

The truth is yet to come out but the incident shows the Corbett tigers have more enemies than just professional poachers.

TOP photo features of the week

...

article