Photographs: Sahil Salvi Neeta Kolhatkar

Residents, civic officials and architects tell Neeta Kolhatkar what went wrong at the Campa Cola building complex in Mumbai, which has grabbed the attention of no less than the Supreme Court of India.

In the 1980s, Pratibha building in South Mumbai's posh Peddar Road area exposed how builders were flagrantly violating construction norms. The 36-floor building eventually faced partial demolition for violating FSI norms.

Around the same time, another controversy was brewing some kilometres away in Worli, south-central Mumbai. The people involved in cooking up the controversy were Yusuf Patel, a fading smuggler-turned-developer, an influential and renowned architect who was already in the news for wrong reasons (the Pratibha building), other construction partners and few not-so-innocent flat buyers

Here, too, as in the Pratibha building case, many of the floors were not regularised. But residents still went ahead and grabbed the apartments being given away at half the market price.

This week, after a protracted legal battle, civic authorities armed with a Supreme Court order marched through the complex gates with bulldozers to raze the illegal floors that houses 102 residents.

At the eleventh hour, the Supreme Court extended a lifeline and stayed the demolition till May 31, 2014.

This is how intense the Campa Cola housing society case has become.

Unlike the so-called 'squatters' of illegal occupants of government land, the residents of the society are influential individuals whose staff were working out strategies with the media in the compound when the Supreme Court passed its order.

Neeta Kolhatkar spoke to the parties involved in this case, assessing what went wrong in this complex case.

Please ...

The Campa Cola controversy: Who is to blame?

Photographs: Hitesh Harisinghani/Rediff.com Neeta Kolhatkar

The Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai had leased the property to Pure Drinks Ltd -- then the franchise for Coca-Cola and later the makers of the Campa Cola drink after Coke was kicked out of India -- in 1955.

The factory issued a lock-out and sold off the two plots it held to five builders after obtaining sanction from the municipal corporation.

Primarily, Yusuf Patel and B K Gupta entered into agreements with PSB Builders in 1981 to develop the plot.

Patel's switch to real estate was paved by the political clout he enjoyed.

Gupta was an influential architect who had worked on well-known city buildings, including the controversial Pratibha building. Few mention PSB Builders today.

The industrial plot was later converted into a residential plot.

By 1985-1986, the seven buildings were mostly constructed. The builders, instead of sticking to the original plan, altered the number of floors in each building.

In the interim, the municipal corporation issued a stop-work notice under the BMC Act and slapped a notice for imprisonment under the Maharashtra Regional Town Planning Act, 1966.

Under the MRTP Act, the BMC alerts the police to arrest offending parties. In the 1980s, rarely did powerful people get arrested under the Act.

Former police officer Y C Pawar told Rediff.com, "The 1980s were a peak time for the underworld. Smugglers and gangsters began entering real estate. Even though Yusuf Patel was fading, the police would not have arrested him. There were few warrants out in Patel's name, but he was given shelter by the wife of a former chief minister."

Please ...

The Campa Cola controversy: Who is to blame?

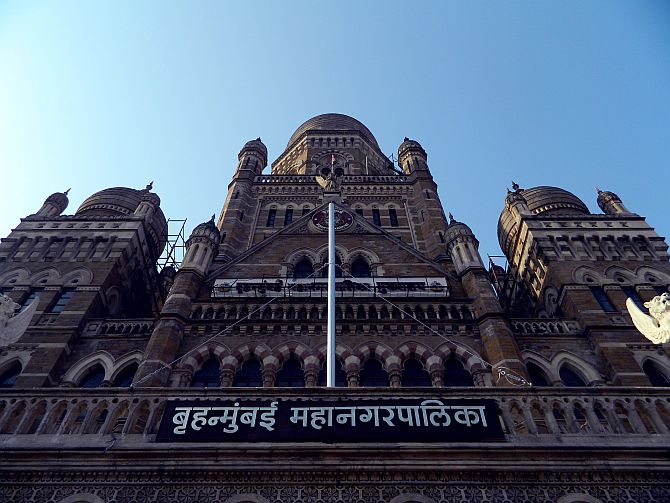

Image: The headquarters of the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai.Photographs: Jyoti Parekh/Wikimedia Commons Neeta Kolhatkar

Jayant Tipnis, once an architect for the Campa Cola buildings, told Rediff.com, "The builders lost interest for whatever reasons. Gupta's licence was cancelled in 1984 after the demolition of the Pratibha building. At that time, the BMC requested me to take over as architect. The BMC had already issued a stop-work notice, but the builders refused to stop the work."

Many believe the civic authorities did not penalise the builders and instead harassed the residents.

Mumbai Municipal Commissioner Sitaram Kunte told Rediff.com, "The BMC does not have the powers to demolish high-rise structures. The BMC does not have the machinery, and the access to private properties is denied. We only have the provision to issue stop-work notices. There needs to be an amendment in the original BMC Act to allow us to demolish any unauthorised structure. We can only issue orders."

"This is not as easy as most accuse us of not doing," Kunte added. "These are high-rise buildings. Take the example of another building, Palais Royale at Worli Naka (in south-central Mumbai). All floors from 43 to 56 are illegal and we have issued stop-work notices. But we do not have the power to seize the machinery and seal their properties."

"Moreover," he pointed out, "we will have to call for contracts to acquire the machinery to pull down these structures."

Asserting that he stands to lose the most, Gupta blamed the BMC for the fiasco.

"I am sympathetic to the residents even though they were aware of the situation of non-regularised structures. The main culprits are the BMC, who are liars. I had written to them, informing them that the builders who came later had violated norms, but they did not take any action," Gupta said.

"It is true the BMC issued a stop-work notice and I paid up the fee. I am the one who has lost the most in this project," he added.

The BMC initially demanded Rs 5.85 lakh (Rs 580,000) from the builders for regularising the illegal floors. Gupta paid up.

Later, the BMC issued another notice demanding Rs 11 lakh (Rs 1.1 million), claiming that the initial fee charged was not enough. By then Gupta was out of the project and the other builders refused to comply.

"I had approached the BMC to get the excess floors regularised," Tipnis said. "Gupta paid the initial fine, but some elements were not cooperative about paying the pending amount. I don't know whether the residents were aware of the developers losing interest."

Please ...

The Campa Cola controversy: Who is to blame?

Image: A bulldozer forces down the gate at the Campa Cola compound.Photographs: Sahil Salvi Neeta Kolhatkar

When Rediff.com spoke to residents, the outrage against the BMC was evident.

"No notices were pasted on our walls. Why couldn't the BMC do that? They are servants of the politicians, not of the public," said a visibly angry Mehnaz Irani.

A couple who did not wish to be identified by name for this report, said: "We were aware that 50 percent fee was to be paid. We do not know about the rest. But that does not mean that we should be denied our basic fundamental rights like a water connection."

As the media raised the Campa Cola issue, with the owner of a public relations agency working out the strategy from the complex, it comes as no surprise that the issue was smartly positioned from the demolition of the illegal floors to "innocent, poor" middle-class folk being forced to live on the streets.

The one fact that got left out in the strategy to save this complex was that the flats were bought at cheap rates; in fact, way below the market rate.

"The market rate at that time was Rs 1,000 to Rs 1,200 per square feet while the residents paid as low as Rs 600 to Rs 800 per sq ft and the status known is that all floors above the fifth were illegal," said Tipnis. Gupta confirmed this.

The residents from 1989 till 2004 used water supplied by tankers as the municipal corporation did not provide regular water connections to residents.

"These residents are smart," an official from the state urban development department told Rediff.com, "They have installed a small water purification plant to purify the water they got from the tankers. They always found ways to work around their situation."

Please ...

The Campa Cola controversy: Who is to blame?

Image: Campa Cola residents celebrate the Supreme Court stay on the demolition.Photographs: Sahil Salvi Neeta Kolhatkar

All these years the residents continued to live without municipal water connections and paid double the property taxes (because the irregular flats did not have an Occupation Certificate, a document issued by the municipal corporation prior to residents moving in).

"If residents do not have an OC, the BMC collects double the property tax. A few years ago, some residents filed a civil suit against the BMC in a city civil court," Tipnis said.

Later, the residents moved the high court for getting a water connection after which their case went downwards.

When the high court ruled against them, the residents moved the Supreme Court, which too called for the illegal floors to be demolished before granting a stay on November 13 till May 31 next year.

"It does seem that the residents were misled. It is true there was a matter pending in the civil court. The residents made a mistake here," Mangal Prabhat Lodha, the Bharatiya Janata Party MLA from Malabar Hill who supports the Campa Cola residents, told Rediff.com

Leaders of most politicial parties protested the BMC demolition order. In fact, a source in Chief Minister Prithviraj Chavan's office said, "The political leadership that wanted to help the residents has harmed them more than they can imagine. It is inappropriate to blame the civic authorities for following a Supreme Court order."

While the residents have got a breather, the Supreme Court on November 19 will address the issue of regularising the illegal floors of the Campa Cola compound buildings.

Asserting that this could set a benchmark, Municipal Commissioner Kunte sounds a word of caution for the public.

"People need to be more responsible when buying property and diligently get more information on the property and the builder rather than blame all others. It is their responsibility."

article