| « Back to article | Print this article |

'Just the fact of Obama staying at Mumbai's Taj hotel matters'

Among the briefing papers that Under Secretary of State William Burns, accompanying United States President Barack Obama on his trip to India, is expected to give the president on Air Force One en route to Mumbai are two reports on US-India relations published on the eve of his trip by the Centre for a New American Security.

Titled Natural Allies: A Blueprint for the Future of US-India Relations, and Obama in India, Building a Global Partnership: Challenges, Risks, Opportunities, they are authored by Mumbai-born Dr Ashley Tellis, now a Senior Fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

In an interview with Rediff.com's Aziz Haniffa, Dr Tellis explains how Obama can leave his stamp on the India-US partnership by his visit.

In your report in the run-up to President Obama's visit, you had strongly advocated two symbolic gestures that he could deliver on and predicted if he does, they would electrify the Indian polity -- US endorsement of India's bid for a permanent seat in the UN Security Council and a strong condemnation of Pakistan-based terror attacks on India. Are these expectations realistic?

On the UN Security Council, I have no idea how Obama is going to come out. It's a decision that he will have to make personally.

My own view on that is that the longer the US waits, the more meaningless the endorsement becomes.

At some stage, there will be a decision about the future of UN reform and we are rapidly reaching the point where India's candidacy for a permanent seat is already inevitable.

And so, for the US to drag endorsing India's candidacy for much longer puts it in the position where it basically loses the benefits of the endorsement.

On the second issue, it's less a condemnation of Pakistan as much as it's an effort to show solidarity with India. That is really the important thing -- that in the struggle that India is going through, the US must be seen very clearly as being in India's corner.

And, Obama should do that, one, because Pakistani-based terrorism is not a problem that India faces alone. It's part of a common problem that the US faces as well.

And, two, because the US has a relationship with Pakistan; consequently, it puts Washington in an awkward situation where one of our partners, Pakistan, also turns out to be an assailant, where another partner, India, is concerned.

And so, the more important point is to establish or affirm solidarity with India and clearly state that terrorism from Pakistan is a threat that we face in common and therefore the US will support India in every way it can.

Perhaps because it may address the continuing doubts in the minds of the Indian polity about perceived US double standards when it comes to the war on terror, particularly Pakistan-inspired terrorism against India?

So, would this be an opportunity to make clear that the US is equally concerned over terrorism directed against India and not just terrorism directed against it?

Absolutely. In this context, whoever thought it up did the president a great service by having him stay at the Taj Mahal hotel in Mumbai. That really makes a point which is quite powerful.

Just the fact of him staying there matters -- and he will certainly meet with employees of the hotel and the victims and all the groups there were part of that whole tragedy.

That will speak very, very loudly. So that's very important.

But I don't see how he can get away without saying anything on the larger subject of terrorism affecting India -- the terrorism emanating out of Pakistan -- because this is something India lives through day in and day out.

So, a public statement would in my judgment be essential.

'Obama can convey that partnership with India is tied to US national interests'

That is certainly something that the administration and the Indian government have been discussing now for several months. But I think the Entities List issue is minor, to be honest.

The real issue is bringing India into the larger nonproliferation regime. The Entities List issue is only one dimension of it.

And, in many ways, it is actually more symbolic than substantive, because even if you are an entity on the list, you can still get US-controlled technology.

It's not as if being on the Entities List means that you don't have access to US high technology. It simply means that there is a licensing process that you have to go through, but the technology is available. So, in that sense, it is more symbolic than substantive.

But the larger issue is whether we can consummate the vision underlying the US-India civil nuclear agreement: That is, making India a full partner in nuclear cooperation, integrating India into the four global regimes that were discussed in 2006, and working with India to expand the growth of nuclear energy worldwide. It's along these dimensions that I see the real payoff.

So, to my mind, the Entities List is certainly important, but it's not the be-all and end-all and friends of the US and India do themselves a disservice when they focus just on the Entities List to the neglect of all the others.

President Clinton's visit in March 2000 was seen by many as a transformational visit. President Obama too apparently has said he wants his visit to be transformational with a grand vision.

But can it be transformational or is this a utopian expectation because you can't always have transformational presidential visits?

I believe that's fair -- because I don't believe the bilateral relationship could handle that many transformations! Once every decade is indeed good enough!

But Obama's visit can be transformational in another sense, in that he provides clear assurance that his administration is doing what is necessary to sustain the American partnership with India he inherited from both his predecessors.

There have been some doubts about this -- expressed both in the Indian press as well as occasionally in the US press.

What Obama can do, therefore, which is important, is the following: He can say in effect, "What my predecessors, both Clinton and Bush, have done regarding India is something that is fundamentally in the interests of the United States. It is not a gift given by one particular administration or another. It is really part of what America's larger national interests require."

And, if he can convey this through his actions and his words and through all the events that he participates in, that would be a big message that survives beyond just the visit.

When people begin to think that a strong US-India partnership is now part of the permanent architecture of global politics, that is transformation. That is what Obama has a chance to convey.

So, I am not one of those who is pessimistic, because on this fundamental question, I think three American administrations now have got it right. And Obama can drive that point home by emphasising that the US partnership with India goes beyond administrations, goes beyond individual presidents, and that it is deeply tied to the vital national interests of the United States and that this national interest is enduring.

I believe that is the best message Obama can leave behind.

'If the problem is Pakistan, then we must confront Pakistan, not India'

I think it is the wrong question to ask -- in the first instance. To my mind, the first and most fundamental question is not what will India do for us, but rather, is a strong and independent India in American national interests?

If that is the real question, then, the fact that there are bilateral disagreements is completely incidental, because as long as the United States believes that a fundamentally strong India, even if it is independent, is in its interests, then, all the disagreements we have on any issues become entirely secondary.

Let me make one other point, which again gets lost in the debate. If disagreements become the index of whether the US can have strategic partnerships, then by definition, the United States will have very few strategic partners.

If you look, for example, at the US-UK partnership, or the US-Japan partnership, and so on and so forth, you will find that there are important disagreements on various issues; yet, that does not prevent these countries from being able to collaborate to the degree dictated by their national interests.

In that sense, the US-India partnership is no different. India will reflect, to a greater or lesser degree, the relationship that the United States has with many countries in the world, including its formal allies.

That to my mind is again testimony that what binds us is the larger vision and that larger vision revolves around collaborating to create a particular global geopolitical environment that serves our common interests.

You have also called for a very candid conversation between Obama and Dr Singh on Afghanistan, but cautioned Obama from asking India how to placate the Pakistani army. Why were you so strong on this issue?

Is this because of the perception in some administration circles, including in the Pentagon, that less Indian involvement in Afghanistan would make the war on terror with the full cooperation of the Pakistani army less complicated?

People tend to confuse the Pakistan problem with the India-Pakistan problem. There is a Pakistan problem which centres on the Pakistani military's unwillingness or inability to fully partner with the United States in counter-terrorism.

That is clearly a problem -- we know that -- because the Pakistani military can't or won't deliver on issues relating to, at least, Afghanistan. Nobody has any difficulty accepting that fact. The question, of course, is, why?

The problem starts when people conclude, all too hastily, that Pakistan has not been able to deliver on counterterrorism because of India -- and, therefore, India must do something to satisfy Pakistan so that Pakistan's behaviour may change.

I believe this logic is completely misguided, because if the problem is Pakistan, then we must confront Pakistan -- not confront India en route to Pakistan.

If you look closely at this issue, you will quickly discover that the problem is not an objective one. It's not something that can be fixed in India in order to change Pakistan's behaviour.

It is, first and foremost, deeply a question of Pakistan's mindset or, more precisely, the Pakistan army's mindset, and it is deeply connected to the Pakistani military's role within its own state.

Unless Washington confronts these two issues, which is the Pakistan military's inveterate opposition to India and its desire to protect its primacy within Pakistan, the problem of US-Pakistan counterterrorism cooperation will not be solved.

These two issues have very little to do with India directly. India could do all the US asks of it and that would still not be enough to change the Pakistan military's behaviour on counterterrorism.The reason my paper was so emphatic about this issue is because I fear that, unless the US starts thinking about the problem correctly, the president could end up attempting to lean on the Indians rather than confronting the real problems in Pakistan.

'Current troubles in US-China relations make it clear why India is immensely valuable'

My sense is that this administration, to its credit, at least in more recent times, has actually gone out of its way to do that.

You mean after that initial mistake in Beijing (in terms of the US-India joint statement that was read in New Delhi as designating China a supervisory role in South Asia)?

That's right. They have clearly indicated that the US-India relationship is really on par with the best and most important relationships the US has in the world.

I am not sure that Obama needs to go out and say anything about China in India because the current troubles in US-China relations make it clear why the relationship with India is immensely valuable.

You mean, if you say that, you'll just complicate things and lead to lending some credence to the theory by some that the US-India strategic partnership is in some ways an attempt on containment of China and all that?

Exactly -- and that's counter-productive. The Chinese have understood very clearly that the US-India relationship is intended, among other things, to protect a certain geopolitical balance in Asia.

Everyone in Asia and globally understands that fact clearly. That India and the rest of the powers on China's periphery -- Japan, South Korea, Singapore, Vietnam, Indonesia -- are already reaching out to one another and to the United States, again, is clearly evidence that there are common concerns about China.

So, I don't think that, at this juncture, the US needs to be talking more about China than is necessary.

In terms of US expectations, you worked intimately on the nuclear deal negotiations and the other day Nick Burns (former under secretary of state in the Bush administration who was the key US interlocutor in the US-India civilian nuclear agreement negotiations) made no bones about it that the Indian nuclear liability bill could jeopardise the US-India nuclear deal.

And, since this is the centrepiece of the envisaged US-India strategic partnership, could impact adversely progress on that front.

So, is this something that needs to be resolved expeditiously?

Let me make two points here. First, the nuclear liability bill that was produced at the end of the legislative process in India, was not the liability bill that Prime Minister Singh and his government introduced or wanted to have legislated.

They had a clean and good text when they introduced the bill in Parliament. The problem is that they did not have the votes necessary to get the kind of legislation they would have liked. And so, what ended up was the product of legislative compromises.

So, the first point to keep in mind is that this bill does not reflect the government's core preference. It reflects essentially the fact that the government simply did not have the votes necessary to enact its preference.

Second, the government is very sensitised now, given what it has heard not only from the US, but also from its own private industry -- from CII (Confederation of Indian Industry), FICCI (Federation of Chambers of Commerce and Industry), Larsen and Toubro, and NPCIL (Nuclear Power Corporation of India Limited).

They have understood clearly that this bill makes it difficult for private industry to participate in India's nuclear electricity expansion. So, they are right now looking for ways to -- while protecting their national interests, while respecting their legislation -- assuage the anxieties of the private sector both domestically and internationally.

I think they will find a way to do it because they know very well that there is only one test at the end of the day: It's not what the United States says or what India says, or what any politician or pundit says.

It's ultimately a market test. After all is said and done, if individual companies are reluctant to participate in India's nuclear expansion, then it does not matter what any government or any of us say.

I think the prime minister and his advisers understand fully well that the proof of this pudding is going to be whether the private sector joins in the eating. And if they join in the eating, then it really does not matter what any of us think about the legislation.

'Obama can show that this is a partnership that pays off'

It can help Obama in two or three ways. The first is that he can show that he has sustained a relationship which two of his predecessors very carefully nurtured -- that he did not drop the ball, that he has actually taken it further.

That is important to him personally -- and, of course, to the United States. And I think the American public will appreciate this as well.

If you look at the polling, for example, Pew's polls of Americans and their views of India -- the results are enormously heartening. Americans overwhelmingly see India as the kind of partner we'd like to have, a partner that we want to have.

So, if Obama reiterate this point clearly, it would help him politically, including with the Indian-American constituencies that helped to elect him.

The second is simply in the practical things he does there. If he ends up strengthening the partnership, if he is able to convey to India that whatever its anxieties are, the United States is going to stay steadfast in that relationship, that is a big payoff for the United States at large, because again we are looking to the future.

This is not a partnership whose benefits we measure in a six-to 10-week period. This is a partnership to be measured in a six-to 10-year period, if not a six-to-ten-decade period.

The third is if he can show that this is a partnership that pays off -- literally.

If he can -- as he will -- bring back contracts, deals, buys, he can tell his audience at home, "Look, this is not simply a symbolic relationship, it's a relationship that's paying off in actual bread and butter terms for the United States."

And when he speaks to Indians, he can tell his Indian audiences that "you are getting from us the best of American technology, the best of American capital, the best of American managerial expertise."

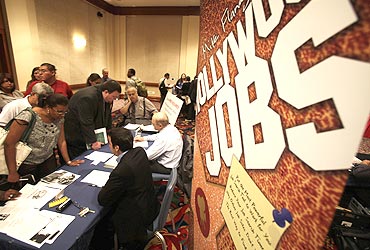

I guess at a time of 10 percent unemployment domestically, showing that he's trying to create job opportunities through this India partnership, would hopefully help justify his trip?

Of course. But he has to do two things where the domestic audience is concerned. One, is, of course, meeting short-term expectations, showing that the bilateral relationship paying off in bread and butter terms. That's very important.

There is also another dimension that he would do well not to overlook, which is, there are great expectations in this country that over time the United States will have friends as it deals with the major changes of the future.

And he has to be able to show that whatever he does in India is putting in place the building blocks for sustaining a partnership that will matter to the United States over the longer term.

There are many in this country who care about this issue because it is intimately linked with America's ability to preserve its own power and wellbeing in the international system. So, he has to speak to that as well.

It's got to be a nice balance between the short and the long-term benefits.