Photographs: Swarupa Dutt Swarupa Dutt

It’s been a year since their daughter, their sister, died of rape-inflicted injuries so brutal, that doctors treating her said they had never seen anything like it. A year that the family has spent scrambling to courts for justice. There will be no closure, they say till all the five men are hanged. Swarupa Dutt reports.

Her brother can remember just one day in the last one year that made him happy.

September 13, 2013; it was a Friday, he says. The Saket fast-track court had handed out the death sentence to all the four adults convicted of brutalizing and raping his sister, who the media called, Nirbhaya.

Gaurav Singh says people in court clapped as he did and wept as he did. “My parents, my brother … we were so happy. Finally, she had been given justice. This is what we had wanted. Every day, we had prayed that they should be given the death sentence. My sister’s wish was that they should be burnt alive,” says Gaurav.

Of her wounds, additional sessions judge Yogesh Khanna had said while explaining how he arrived at his decision to treat it as a rarest of rare case, meriting the death sentence: "The facts show that the entire intestine of the victim was perforated, splayed and cut open due to repeated insertion by rods and hands. The convicts, in the most barbaric manner, pulled out her internal organs with their bare hands as well as with rods and caused her irreparable injuries, thus exhibiting extreme mental perversion not worthy of human condonation."

Debates raged about how the death sentence would not reduce the incidence of rape. How the five men should be given a chance to redeem themselves and integrate into mainstream society. How these men from the underbelly of India were victims of the socio-economic conditions that bred them. Sociologists pointed to research carried out by Harvard University that indicates longer prison terms make juveniles repeat offenders. Panelists on the TV debates post verdict said of the juvenile: “That poor, young boy should be given a chance to reform.”

The Singhs say they switched off the TV. It was unbearable, they said. Says her mother, Asha, “Had it happened to someone they loved, their own daughter, would they say the same thing? My daughter begged for mercy, but they raped her and dragged her by her hair and threw her out of the bus. And these people want those monsters to be shown mercy!”

...

'Even after a year, the men are alive and well in jail. The juvenile has a room to himself'

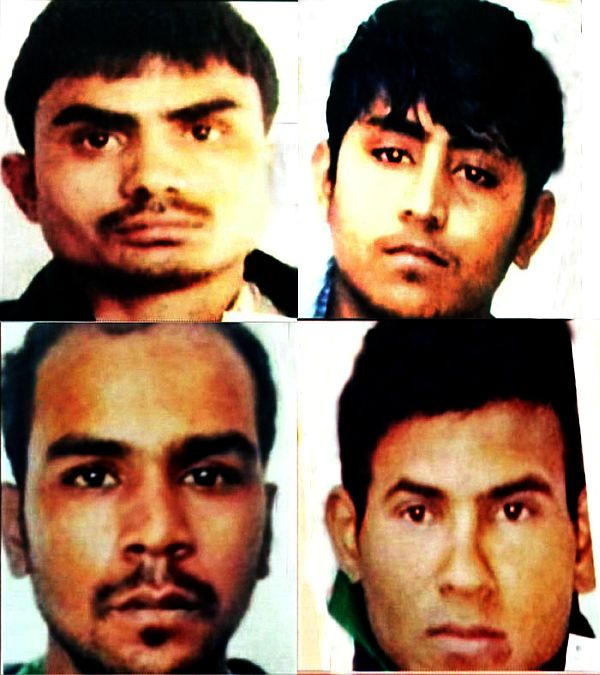

Image: Delhi gang rape convicts (clockwise from top) Pawan, Vinay, Mukesh and AkshaySwarupa Dutt

The ‘poor young boy’, the unnamed juvenile who is in a reformatory home, has shown no signs of remorse, say media reports, and uses abusive language with the staff and threatens welfare officers.

As for the four adult convicts, the case is now being tried in the high court, after their lawyers appealed the verdict.

For the Singhs, this means their lives are on hold, waiting yet again for the verdict and a reconfirmation of the death sentence. “We are physically and mentally tired of the trial. Even after a year, the men are alive and well in jail. The juvenile has a room to himself so that he’s not harmed. What is the point of a death sentence, then? They have to be hanged quickly,” says Gaurav.

The family had believed that after the verdict, they could begin life afresh in their new apartment gifted by the Delhi government in a middle-class neighbourhood in Dwarka. The boys had been admitted to premier academic institutions and the government had promised them jobs. And there was the “compensation money”, from the government, much more than Badrinath, the father, could earn in his lifetime.

Asha says she’s grateful to the government, but hurt at insinuations that they’ve made a killing from their daughter’s death. “All I have asked of God when she was in hospital was to save her. Don’t let her die. Do you think this house and money compensates for what we have lost? We think of her every day. I think of December 16, when she waved goodbye and told me she’d have dinner at home. I think, why did I let her go. We were poor then, struggling to make ends meet, but we were happy.”

Neighbours, friends, teachers, attest to that. They speak of the two brothers who aspired to be engineers, astronauts, and of their sister who gave birth to these ambitions and told them it was possible to achieve their dreams. They tell of their sister, who worked nights at a call center in Dehradun to fund her tuition fees in physiotherapy. She was on the brink of joining a reputed hospital in Delhi as a physiotherapist, last year, when she hopped aboard that bus, with six psychopaths on board.

...

'I have to let go, but I just can't'

Photographs: Reuters Swarupa Dutt

Gaurav, who is studying aerospace engineering, says he will never let his sister’s dreams die. “But I simply don’t feel energized to achieve what Didi and I dreamt of. She wanted me to study, to appear for my exams, so I’m doing it. I know I should think about the future, I can’t live in the past. I have to let go, but I just can’t. I keep thinking of her in hospital. And what they did to her,” he says.

Closure he says can only happen when the four adults and the juvenile are hanged. The family has moved the Supreme Court challenging the Juvenile Justice Act. They are also seeking a criminal trial against the juvenile, now 18, saying he was an equal participant in the assault and rape of their daughter.

“Use bhi wohi saza milni chahiye jo doosron ko mili thi. Usne bhi toh wohi jurm kiya tha, (He should be given the same punishment as the others. He committed the same crime as they did)” says the family. The juvenile was given a three-year sentence at a reformation home. He will be a free man in December 2015.

For India, it has been a year that saw unprecedented street protests demanding safety for women, justice for the girl. When rape and sexual abuse survivors found strength and catharsis in Nirbhaya’s family’s unshakeable resolve to name her and shame her rapists.

A year which saw vicious debates between conservatives who blamed chop suey and westernization and liberals who blamed patriarchy and centuries of sexist tradition. A year in which the government set up the Justice Verma Committee which recommended amendments to law to provide for quicker trial and enhanced punishment for criminals accused of committing sexual assault against women.

So, on December 16, the Singhs will hold a memorial meet at the Constitution Club in Delhi and on December 29, the date she died, a small prayer meeting to perform the one-year rituals.

For the Singhs it’s been a year of waiting for the death sentence, a year of learning to live without their daughter, a year of learning to cope with their grief and outrage.

This year, they believe, will be no different.

article