Photographs: Abhishek Mande/Rediff.com

Mahendra Tarwala had a one-of-a-kind job. For over half a century, he sent telegrams on behalf of grain merchants in Mumbai and ran his house on the commission he made. On Sunday, July 14 when the government drew curtains over the 163-year-old service, the 70-year-old was left jobless. This is his story.

Every evening from Monday to Friday, Jayashree Tarwala settles before her television to watch Taarak Mehta Ka Ooltah Chashmah because "only good things happen there".

Tarwala could do with some good news in her life right now. Her husband Mahendra has just lost his job; it was the only thing he did for over 50 years and now, at 70, it is too late for him to start anew.

It also doesn't help that Mahendra Tarwala was, till Sunday, possibly the only person in Mumbai doing what he did -- sending telegrams for a living. He charged Rs 50 to wire messages on behalf of hundreds of grain merchants in the city to their suppliers across India.

With the 163-year-old service having drawn to a close on July 14, Mahendra Tarwala and his wife have nothing to look forward to, except of course a television sitcom.

***

Tarwala remembers the day he first heard the news. It was June 10 and he had just renewed his monthly bus pass. He walked from the depot to the Central Telegraph Office where one of the clerks broke the news to him -- the telegram services would be shut down soon. Tarwala's first reaction was this: "But I just renewed my bus pass for the month. It cost me 325 rupees!"

It would be a while before the gravity of the news would sink in, before he would realise that the Rs 325 he'd just spent would be the least of his worries. When it did, he broke down in the grand hall of the office that he had been frequenting since he was a little boy.

***

"That isn't my real name, you know that, right?" Mahendra Tarwala's eyes light up. "Our family name is Batavia. People began to call my father Tarwala because he sent telegrams, taars, on other people's behalf. I used to carry his lunch to his office as a child and before I knew it, I joined the business. I must have been 17 or 18 (years old) when I started full time but I was already working from when I was much younger. Perhaps 10 or 11."

Tarwala doesn't seem to have any romantic notions of the telegram. He wasn't fascinated by the technology or the amazing speed at which the letters his father typed out on a telegraph form would travel thousands of miles within moments.

These things never occurred to him and there was never an occasion when he could romanticise about his job, certainly not when there were always mouths to feed.

"We were 13 siblings. Some of them died when they were young. Now only seven of us survive. We lived in a 600 sq ft house. My father married four times," Tarwala says all of this seemingly in a single breath but with a perfectly straight face.

His wife, sensing my shock, clarifies that the senior Mr Tarwala wasn't polygamous and re-married only after the previous wife passed on... or at least that is what I understood of a convoluted explanation that involved a lot of wild hand gesturing, referring to old customs and something about one of them being possessed.

Unlike his father, Mahendra has stuck to one wife who bore him two children -- Vaishali, 38, who is now married and settled happily in Pune, and Nitesh, 32, who is currently unemployed.

Please ...

He lost his only job... because the telegram died

Image: Even in the face of adversity, Jayshree Tarwala is the epitome of dignity.Photographs: Abhishek Mande/Rediff.com

The Tarwalas stay in a 300 sq ft apartment in the congested Kalbadevi area of South Mumbai. From one window, the view is that of the verandah of another chawl where Mahendra was born and raised along with his multiple siblings. The other side opens up to a terrace of sorts where the family feeds pigeons.

It is a spartan home -- the living room has a television set, a diwan, a small iron cupboard, few foldable iron chairs and a table on top of which sits an old Remington typewriter with the letters 'gton' form its name having fallen away.

By these standards, the kitchen is spacious. It makes up for about one-third of the house; it has a couple of large iron wardrobes, a refrigerator, a microwave and enough space for a person or two to sleep comfortably. It isn't the most conducive home but it exudes a certain warmth. A lot of it, I suspect, has to do with the lady of the house who has done a marvellous job of keeping it all together.

Even in the face of adversity, Jayshree Tarwala is the epitome of dignity. She welcomes you with a smile, insists on offering you tea, accompanies it with about half a dozen goodies, speaks eloquently in Hindi and Gujarati and doesn't seem prone to anger like her son or frequent emotional breakdowns like her husband.

"It is difficult," she says, sounding perfectly calm, "We really don't know what we'll do now. I don't understand why they had to shut it down?"

She pauses for a moment before posing the most difficult question, just as calmly: "How can you re-open dance bars and shut down telegram services?"

There is no way you can tell her the two are unrelated.

The reason no one's going to talk about the latter is because the closing of telegraph services has affected just o-n-e family.

***

Nitesh Batavia refuses to be photographed. He also refuses to take his father's last name. At 32, he is unemployed and likes to believe he is a bit of a Casanova. He has recently broken up with his girlfriend of about four years "out of mutual consent" and isn't in a mood to get married any time soon.

"I do not trust women," he says nonchalantly. "I'd rather have a live-in relationship."

There is, apparently, no one who can impress Batavia enough, no one who has done him any good or any favour, not even his parents who, by his own account, have invested all of their life's savings and purchased him an apartment on the outskirts of Pune.

And so, on being asked if he feels responsible for them, Batavia's reply is as unsurprising as it is brutal: "No!"

In the winter of their lives, the Tarwalas are pretty much on their own.

***

"I would like to work till my last day. But no one is willing to give me a job. I went to a courier company and they said they would pay me four to five thousand rupees a month," Tarwala says. Even by their frugal standards, that is measly.

He says that his business fetched him anything between Rs 10,000 and 12,000 a month towards the end and though it was difficult to manage, they did it anyway. Even during its peak, the business may not have offered the family luxury but their thrifty lifestyle ensured they had saved up enough for their children. Sadly, they left little for themselves.

Like most of us, Tarwala too derives his sense of identity from his job. This has been his livelihood; it has even given him his name.

"This is the only thing I know because it's what I have done all my life," his says, wiping away his tears, "Till the final day I kept hoping that there would be some miracle; that they would extend it (the services) by a few years. Someone told me BSNL was running in profit. If that is true, they should start it again, no? Do you think they will?"

Please ...

He lost his only job... because the telegram died

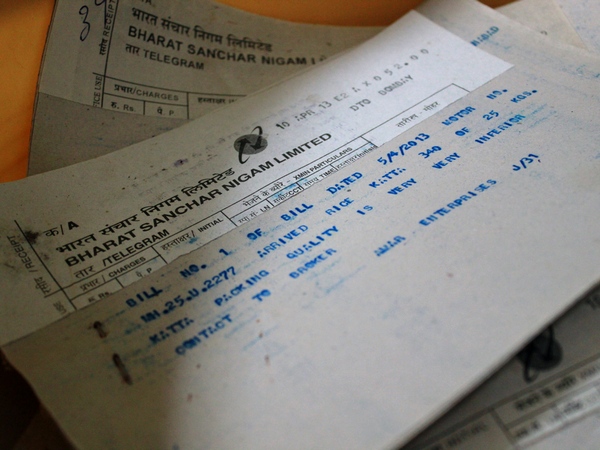

Image: The typewritten remains of Tarwala's career -- receipts and copies of the telegrams he used to send out on behalf of his clientsPhotographs: Abhishek Mande/Rediff.com

Up until last week, Mahendra Tarwala's schedule was rather sorted. He took calls from teh morning till evening from grain merchants across the city, typed out the messages on a telegraph form and towards the end of the day, took the bunch to the CTO from where messages would be wired to cities and towns he had only heard names of.

The content of the message usually had something to do with the quality of the grains. If it was bad, the phrase used was 'very very poor'. If it was worse, it would be 'third class'. All these messages would end with the very same, but grammatically incorrect, line: 'Contact to broker'.

After sending out the messages, he would return home, dexterously pin the receipts to a carbon copy of the message and store them safely.

Copies of the messages, neatly typed, all in capital letters, reveal a certain discipline and consistency. In times of fancy fonts and laser printers, the typewritten remains of his career divulge a private tragedy that may not find even a footnote's space in history.

It wasn't always like this.

"During my father's time, we had an office not very far from the CTO and we employed people. There was so much work. That's how I got started too. Because I wasn't very good at studies, I joined my father in his business. (One of my brothers and) I ran it after my father died," he recollects. "Then he forced me to leave the office to him. He gave me some 56,000 rupees and asked me to go. Since then I have been working from home."

Tarwala's career then followed the trajectory of the telegram. His charges that started at 10p a telegram rose with inflation. In the '80s, he says, he would deliver 500 to 600 messages every day.

"Earlier post offices would accept telegrams so we would go to the nearest one at Kalbadevi. Back then they would accept regular delivery telegrams before 5 pm and express delivery ones after. So I used to go twice, sometimes thrice a day to deliver the messages. When I was away, my wife used to attend to the telephone," he says.

When the Kalbadevi office stopped accepting telegrams, he began going to Princess Street (further away from his house), then to Chinch Bunder (even further) and finally when there were no other places left, he began going to the CTO from where he first started.

***

By the time it was the end, Tarwala was receiving about 15-20 messages each day. Now, after the end, things are worse.

The day I visit his house -- three days after the service has shut -- he has received just two calls. He still types out the messages on the same telegraph form but instead of wiring them, he folds them, puts them in a five-rupee Speed Post envelope, goes to the General Post Office and drops them there. It takes longer for the message to reach its destination and it costs him more.

"Telegram used to cost me 28 rupees, Speed Post costs 39. And they take three days to deliver it. I have told my clients. Some of them are all right. But even then, I will end up making 11 rupees less per delivery. I will have to see how it goes. Most merchants are doing business on SMS now anyway," he says.

The bus pass he purchased last month has expired so he doesn't take the bus anymore; he walks it to the GPO, a distance of about 4 km. He has already enquired about a pass on the new route. It will cost him Rs 90 less.

"That is a good thing, I think," he says earnestly as we sip chai in a tiny store watching the busy rain-drenched street.

Interrupting some small talk we are making, he asks in all seriousness: "Why were people sending out telegrams (on the day the service was shutting down)?"

As souvenirs, mementos, I explain.

"That's strange. Why would you want a piece of paper as a memento?"

As we are about to leave, he knocks over a glass much to the owner's irritation.

"Did I break it?" he asks. I nod. "Oh that is a good omen. It's a sign of wealth to come," he says, grinning, as he walks away and disappears into the crowd.

***

When did you receive your last telegram? I ask.

"No one's ever sent me one," he replies with a shrug.

And when was the last time you sent one?

"That is what I did, every day since I was..."

No, I mean a personal telegram. One you sent... to someone you know.

(Pause)

"Over 30 years ago. To my wife's sister in Jamnagar. To tell her of Nitesh's birth."

Never after that?

"Of course not! Why would I want to send anyone a telegram?"

article