| « Back to article | Print this article |

'Promote democracy' a slogan, not a policy

Berating New Delhi for abandoning the cause of democracy in Myanmar ignores the strategic compulsions for doing so, says Harsh V Pant

Berating New Delhi for abandoning the cause of democracy in Myanmar ignores the strategic compulsions for doing so, says Harsh V Pant

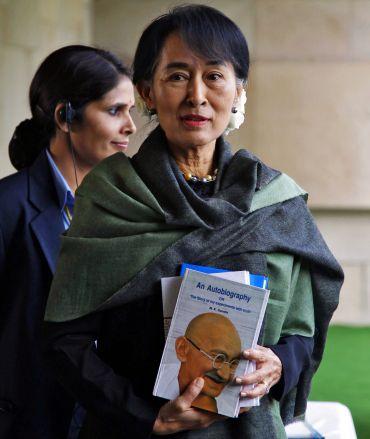

Delivering the Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial Lecture last week -- 17 years after she was awarded the Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial Prize in 1995 -- Nobel Peace laureate and Myanmar opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi underlined the significant roles that Mahatma Gandhi and Nehru have played in shaping her political and intellectual trajectory.

Suu Kyi was in India after 25 years -- of which she had spent nearly 15 under house arrest -- and she suggested that the thoughts and actions of the leaders of the Indian Independence movement provided her with ideas and inspiration.

New Delhi rolled out the red carpet for one of the most influential pro-democracy icons of our times, as India's ties with Myanmar come under scrutiny once again. There are growing voices in India and abroad berating New Delhi for abandoning the cause of democracy in Myanmar in recent years.

After being a strong critic of the Myanmar junta, India muted its criticism and dropped its vocal support for Suu Kyi since mid-1990s to help pursue its 'Look East' policy aimed at strengthening India's economic linkages with the rapidly growing economies in east and southeast Asia.

More important has been the realisation that China's profile in Myanmar has grown at an alarming pace. India's ideological obsession with democracy made sure that Myanmar drifted towards China, since India found it difficult to toe the western line on Myanmar. It was stuck between the demands of its role as the world's largest democracy and the imperatives of its strategic interests

The large Burmese refugee community in India is a product of the 1998 military crackdown in Burma. Indian elites have long admired the freedom struggle led by Suu Kyi, who was honoured with one of India's highest civilian awards in 1993.

The official policy of the Indian government has always been to support the eventual restoration of democracy in Myanmar. But India's strategic interests in Myanmar could not be ignored, especially as China's trade, energy and defence ties with Myanmar surged.

As a consequence, India was forced to take a more realistic appraisal of the developments in Myanmar and shape its foreign policy accordingly. India had a few options but to substantively engage the junta, and it reversed its decade-old policy of isolating the Burmese junta and began to deal with it directly.

Myanmar's President Thein Sein and the country's reclusive military leader, General Than Shwe, were in India last year. The Indian prime minister reciprocated by visiting Myanmar earlier this year.

India's strategic interests demand that India only gently nudge the Myanmar's junta on the issue of democracy. India's relief efforts after the tropical cyclone Nargis hit Myanmar in 2008 earned it great deal of appreciation.

India managed to gain a sense of trust at the highest echelons of the Myanmar's ruling elite and it was rightfully loathe to lose it. Not surprising, therefore, that India remained opposed to western sanctions on the country.

After six years of discussions, India agreed to the building of Sittwe port in 2008 at a cost of $120 million. This will provide an alternative route to connect with southeast Asia, without transiting Bangladesh.

India has also extended a $20-million credit for renovation of the Thanlyin Refinery, but it also supported Myanmar against the US censure motion in an attempt to lure the junta to grant preferential treatment to India in the supply of natural gas. Bilateral trade between India and Myanmar today stands at around $1 billion and is expected to double by 2015.

The junta has cooperated with India in eliminating Naga insurgents who find sanctuaries in Myanmar's border areas. India's long border with Myanmar is an open one where the tribal population is free to move up to 20 kms on either side.

Apart from India's existing infrastructure projects in Myanmar, which include the 160-km India-Myanmar friendship road built by India's Border Roads Organisation in 2001, India is looking into the possibility of a second road project and investing in a deep-sea project (Sagar Samridhi) to explore oil and gas in the Bay of Bengal and as the Shwe gas pipeline project in western Myanmar.

Even as the Burmese military junta was readying for a violent crackdown on monks and democracy activists, the Indian petroleum minister was in Yangon signing a production deal for three deep-water exploration blocks off the Rakhine coast.

While India did support the United Nations Human Rights Council resolution against Myanmar, it tried to tone it down to little effect as it tried to balance its democratic credentials with its desire to retain its influence with the Burmese military government. India has found it difficult to counter Chinese influence in Myanmar, with China selling everything from weapons to food grains to Myanmar.

There is no escaping the clout China wields in Myanmar. Chinese firms get preferential treatment in the award of blocks and gas, apparently in recognition of China's steady opposition to the US moves against Myanmar's junta in the UN.

India will find it difficult to project power in the Indian Ocean if Chinese naval presence increases in Myanmar. China's growing naval presence in and around the Indian Ocean region is troubling for India because it restricts India's freedom to manoeuvre in the region.

The US was concerned that the junta in Myanmar has been using its increasing engagement with India to gain greater global legitimacy. US Assistant Secretary of State Kurt Campbell had suggested that India's growing role in global politics should be used to penetrate the tight military clique that runs Myanmar and that New Delhi should 'encourage interlocutors inside [Myanmar] to embrace reforms'.

The US president, while endorsing India's candidacy for the permanent seat in the UN Security Council, had suggested that his government expected New Delhi to speak up on human rights abuses in Myanmar. Now, Washington is engaging the military junta and has come around to India's point of view.

The generals in Myanmar have taken some radical steps in moving their nation towards civilian rule. Suu Kyi is now part of the political establishment as an elected member of Myanmar's parliament and is engaged deeply with the military junta to find the best alternative for her nation.

This should give India greater strategic space to manoeuvre.

When critics complain that India should be promoting democracy in its neighbourhood, they are articulating a slogan, not a policy. Democracy is but one of the many variables that impinge on Indian foreign policy priorities.

Though important, it can never be the sole determinant of the nation's foreign policy. In Myanmar, New Delhi's middle path has worked well and there is no need to be apologetic about this policy.