'We had become buffoons with Lalu. If you were a Bihari you were seen as a buffoon -- that has changed. Now there's a pride in being a Bihari.'

Part I: 'We took a U-turn under Nitish Kumar'

Seven years after Nitish Kumar became chief minister, the image of the state may have been boosted; but the quest for Bihari pride will remain unfulfilled until chronic failings like illiteracy and malnutrition are adressed, notes Archana Masih in the concluding part of her reportage on the changes in Bihar.

Lalu Yadav and his wife Rabri Devi's 15-year stewardship of Bihar prior to 2005 is widely considered as the time when development hit rock-bottom and crimes went sky-high.

Lalu Yadav and his wife Rabri Devi's 15-year stewardship of Bihar prior to 2005 is widely considered as the time when development hit rock-bottom and crimes went sky-high.

It is a period which has not been forgotten and many feel that fear of Lalu Yadav's return remains Nitish Kumar's biggest political capital. At his recent rally in New Delhi, Lalu Yadav -- who lives next door to Nitish Kumar in Patna -- attacked the chief minister for corruption, declining law and order, and called him a dictator.

When one speaks to people, you realise that they always compare the 'now' with the 'then' -- then being the Lalu Yadav-Rabri Devi years.

A retired school teacher mentions how at a village rally, Lalu Yadav stopped his speech mid-way to ask someone to get a chair for an old woman who was standing in the crowd -- but feels running a state requires more than this sort of "people connect."

"We had become buffoons with Lalu. If you were a Bihari you were seen as a buffoon -- that has changed. Now there's a pride in being Bihari," says a young Bihari, an alumnus of New Delhi's St Stephen's College, who feels that Lalu Yadav's Rashtriya Janata Dal has not played the role of a credible Opposition in the state.

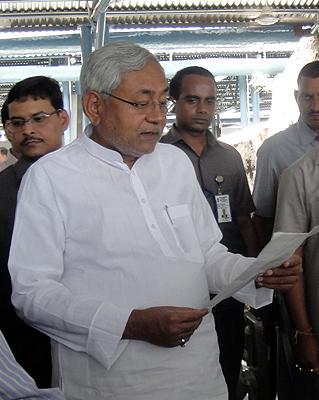

Image: Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar at his Janata Darbar in Patna

The comment reminds me of what Shaibal Gupta of the Asian Development Research Institute had mentioned -- that there was a time when Bihari civil servants serving outside Bihar would not reveal their identity, and how Nitish Kumar has given Bihari identity a new meaning.

Across Bihar, people maintain that things no doubt have improved and Nitish Kumar will get a third term unless, of course, things go drastically wrong, but also concede that corruption has increased.

The state budget has increased from Rs 30,000 crore (Rs 300 billion) to Rs 90,000 crore (Rs 900 billion) and in spite of attempts to plug leaks, adds a state official, even 1 per cent leakage amounts to a massive amount (1% of Rs 90,000 crores is Rs 900 crores/Rs 9 billion).

Also, maximum development has taken place in building roads that have historically been notorious for corruption. Just as there are dry departments, roads is a wet department as far as corruption goes, says the ADRI's Prabhat Ghosh.

"Secondly, Nitish Kumar is banking on the bureaucracy. Once you do that the bureaucracy will ask for a price and corruption is that price," adds Dr Ghosh.

One of the state's bureaucrats tells me that the increase in corruption is "nauseating." A lot has been done to curb corruption -- IAS officers to grassroot workers -- have been sent to jail, but since the inflow of money is like never before, corruption has spiralled, adds the official.

"If I know a person is corrupt but will hesitate to take action because if I send everyone to jail, who'll be there for work for me?" asks the official incredulously but points out that all said and done things are far better than before in Bihar -- governance has improved, the decision-making process has become swift, the cabinet meets regularly and there is lack of political interference.

In the last seven years the wheels of the state have started squeaking back into motion. As Professor Ghosh puts it -- Nitish Kumar has restored its minimal functioning -- law and order, roads, school enrollment, improved hospitals.

In the last seven years the wheels of the state have started squeaking back into motion. As Professor Ghosh puts it -- Nitish Kumar has restored its minimal functioning -- law and order, roads, school enrollment, improved hospitals.

"He is a one-man-show, but isn't it so in Gujarat," says Debapriya Mookherjee, a businessman from Motihari, who ranks roads as Nitish Kumar's major accomplishment and seems confident of him securing a third term.

However, while the chief minister tries to build the state, he has failed to tackle Bihar's feudal-entrenched land issues and not spoken about land reforms which has a bearing on the support of the traditional elite.

Image: People walk down the municipal chowk area in Chhapra. The town's first V-Mart, a retail store, came up recently.

In an example of how India's states are so different from each other -- the support of the elite in a state like Maharashtra means the support of the corporate sector, while in Bihar it translates to the support of the feudal zamindar or the landed feudal elite.

With neither a corporate sector or a social movement, Bihar has had no messiah to break the bone of its feudal structure -- and addressing the institutional problems of land remains amongst Bihar's biggest challenges.

***

"Light ka kya position hai?" is a common question children outside the state ask when they call their parents back home in Bihar.

Outside Patna with its new parks, flyovers, a mall-cum-multiplex -- the villages and towns remain plunged in darkness for long hours -- between 8 to 10 to 12 to 14 hours a day.

It is not as if the state capital has 24-hour power, but the power cuts are miniscule compared to the hinterland.

It is not as if the state capital has 24-hour power, but the power cuts are miniscule compared to the hinterland.

The middle class depends on inverters, generators; the poor on kerosene lamps. Generatorwallahs sell 60 watt points for Rs 300 each -- with Sunday off; while inverters cost anything between Rs 10,000 to Rs 15,000.

Image: A grocery store powered by a generator in Chhapra, Bihar.

The owner of an inverter shop in Chhapra says he sells 500 to 600 inverter sets in the summer. "Since the power situation is bad, business is good," he adds.

Last month a police inspector in town conducted a housewarming ceremony by the light of kerosene lamps and plans to install a solar set on his terrace for electricity.

Rajesh Prasad, a local supplier in Chhapra, says he sells 30 to 40 solar sets each month, mostly for rural areas that get a 40 per cent subsidy from the government.

Bihar's power requirement is 3000 MW, but it gets 1400 to 1500 MW. Hopes are pegged on two National Thermal Power Corporation plants coming up in Barh and Aurangabad in the state while two government plants in Barauni and Muzaffarpur are being upgraded.

In the next couple of years, bijli will improve, claims the state government.

Power theft remains another problem; Bijli chori is a fashion, says an electricity superintendent engineer.

In India, power theft is between 10 to 15%, in Europe it's less than 5%, in Bihar it is 30%, informs researcher-thinker Prabhat Ghosh, pointing out that of the three power plants in the state, the last one -- Barauni -- came up around four decades ago.

Establishing a new power plant which would require Rs 60,000 crores (Rs 600 billion) is not a feasible option for a state with a budget of Rs 90,000 crores, says Dr Ghosh. However, curbing power theft can lead to immediate results.

One of the things Nitish Kumar has done is to restructure the power board and made it three pronged to streamline the power sector. He has also staked his political career by stating that if he does not provide energy by 2015 he will not fight the election.

One of the things Nitish Kumar has done is to restructure the power board and made it three pronged to streamline the power sector. He has also staked his political career by stating that if he does not provide energy by 2015 he will not fight the election.

"In the last term he said he would give roads, which he has. This time he has said electricity, if he manages to do that he will come back to power," says a professional in Patna.

Image: A poster for this year's Bihar Diwas celebration in Bettiah

Invariably compared to Na-MO in Gujarat, the mecca of India's industry, Ni-Ku's Bihar remains bereft of industry, widely considered as the talisman for development.

Travel through the state's plains and you will see enough stone kilns but hardly any factories.

"Where the state hasn't functioned at all, you have to build the state -- and to bring private sector investment you need a robust state," says Shaibal Gupta. "Without electricity and many historical problems, Bihar cannot be an automatic destination for investment like Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat or Karnataka."

Gupta, a long time commentator on Bihar, also believes that the industry-centric, metropolitan-centric, urban-centric strategy of the Government of India post-Independence has resulted in a duality and two extremes of that duality are Bihar at one end and Gujarat at the other.

Hampered by poor infrastructure, and historically dependent on public sector investment, the state is banking on special category status to increases possibility for private investment.

Given the present structure and level of Bihar's economy, industry has still not come to set shop here.

"If you see the economic history of any region in India, first local industry has to be promoted. It has never happened that foreign capital comes in first and is then followed by local capital," says Professor Ghosh.

"Local capital has to perform, show it's feasible, create external links and generate some advantages for outside capital to come in," he adds, citing the example of Uttarakhand which attracted industry after receiving the special category status, but the flow started drying up after a while.

No industry may have come but one of Bihar's silent success stories has been agriculture.

No industry may have come but one of Bihar's silent success stories has been agriculture.

"Production has gone up, procurement has gone up -- it is a silent revolution," says Bandana Preyashi, a young IAS officer who has come to serve in the state capital after stints in Siwan, Bhagalpur and Gaya.

Image: A farmer ploughs his field in Gopalganj district

One of the most beautiful sights in Bihar are its flat fields -- rice, wheat, maize, daal; the bagichas of leechi and aam etc. This year, the state received an award from President Pranab Mukherjee for record production of rice. A farmer from Nalanda district broke the world record for rice by beating a farmer in China.

By these beautiful fields also reside some stark realities about the state that ranks with the exception of Orissa as the poorest state in the India Union.

More than half of its population, according to the 2011 census, lives below the poverty line. It has the lowest literacy rate in the country.

58% children under the age of three are malnourished.

75.8% rural households have no toilets.

In Bihar these realities stick out with startling regularity -- children with matted hair and torn clothes, carrying a load of cattle-feed on their head, walking barefoot on a road blazing under a hot sun.

Patients at a local hospital who can't read the names of departments -- or the various government health banners because they are illiterate.

Bihar has taken great pride in its double digit growth (except two years in the past five) but pulling it out of such persisting lows is the greatest challenges for the keepers of Bihar.

The image of the state has been boosted in the past few years; the quest for Bihari pride will remain unfulfilled without this.

Photographs: Archana Masih

© 2025

© 2025