- Can we make high speed 4G Internet available at 10 cents per GB, and make all voice calls free of cost -- that too in a large and diverse country like India?

- Can we make high-quality but simple breast cancer screening available to every woman, that too at the extremely affordable cost of $1 per scan?

- Can we make a portable, high-tech ECG machine which can provide reports immediately and that too at the cost of 8 cents a test?

- Can we make an eye imaging device that is portable, non-invasive and costs 3 times less that conventional devices?

- Can we make a robust test for mosquito-borne dengue, which can detect the disease on day 1, and that too at the cost of $2 per test?

Amazingly, says Dr R A Mashelkar, the eminent scientist, all this has been achieved in India, not only by using technological innovation but also non-technological innovation.

Dr R A Mashelkar -- Chairman, National Innovation Foundation; former director general, Council of Scientific & Industrial Research, and secretary, Department of Scientific & Industrial Research -- delivered the 2018 K R Narayanan Oration at the Australian National University.

This is what Dr Mashelkar, one of India's leading scientists, said:

Hon'ble Vice-Chancellor, High Commissioner, Professor Jha, ladies and gentlemen.

I deeply appreciate the honour done to me by Australian National University by inviting me to deliver the prestigious 'K R Narayanan Oration'.

Kocheril Raman Narayanan was the tenth President of India, and one of our most accomplished civil servants, distinguished diplomats and stellar academicians.

I met him for the very first time in 1982.

He was visiting my National Chemical Laboratory.

I had the unique opportunity to demonstrate an innovation from my team of a super absorbing polymer -- the Jalshakti, which could absorb water, amazingly, over hundred times its own weight.

I still remember the probing questions that President Narayanan asked me about the potential use of Jalshakti in agriculture in rain starved areas in India.

And then I had the privilege of interacting with him on issues concerning science and innovation in India on numerous occasions.

President Narayanan and I were born 22 years apart -- but his life's story bears a striking resemblance to mine.

He was born in a small village in Kerala; I was born in a small village in Goa.

He walked 15 kilometres to get to school, much like I walked barefoot to a municipal school.

He sometimes stood outside class and eavesdropped on lectures because his family didn't have enough money for tuition.

Due to extreme poverty, my widowed mother could not afford notebooks or shoes, and I remember many nights on which I studied under street lights.

He took his brother's help to copy notebooks and books and return them, and I remember sitting on a footpath, borrowing books from a kind bookstall owner, quickly reading them and returning them.

In fact, we both even share the turning point of our academic lives.

Both of us were Tata scholars.

We both left India, only to return when we were fairly young with a zeal to do more for our homeland, he at the age of 27 and I, at the age of 32.

You can see how right he was.

I would have had to leave studies despite standing 11th among 135,000 students in Maharashtra at the matriculation exam in 1960.

But it was the Tata scholarship of 60 rupees per month for six years that helped me study.

In 1960, when I used to go to Bombay House, Tata headquarters to collect that sixty rupees a month, if someone would have said that you and Ratan Tata, the head of the Tata family, will be among the only seven Indians from the time of establishment of the American Academy of Arts & Science in 1870, who would be elected as Foreign Fellows of that Academy; or that you both will sign the Academy's Fellows book one after the other on the same page on October 15, 2011, I would not have believed it.

And here is yet another validation of what President Narayanan had said.

On March 30, 2000, one of the highest civilian honours in India, the Padma Bhushan, was bestowed on both me, a Tata scholar, and Ratan Tata, head of the house of Tatas.

By whom? President Narayanan, another Tata scholar.

This was the best endorsement of President Narayanan's remarks about moving from the 'sidelines of the society to the hub of social standing'.

CSR 1.0: Doing well and doing good

The Tata scholarships that President Narayanan and I received were a direct result of the sense of corporate trusteeship that the Tatas had always demonstrated.

Perhaps it is not widely known that world's first-ever charitable trust was set up by Jamsetji Tata in 1892, a long time before the Andrew Carnegie Trust (1901), the Rockefeller Foundation (1913), the Ford Foundation (1936) and the Lord Lever Hulme Trust (1925).

The establishment of these trusts was driven by the Tatas' belief in giving back to the people what came from the people.

The meaning of such philanthropy has changed over the years.

What was considered as corporate trusteeship is now being called Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR).

The Tatas did CSR, since they considered it to be their moral responsibility.

The Government of India has recently legislated that 2% of the net profits earned by the corporates must be spent on CSR.

I would call this as CSR 1.0.

Here, part of the surplus wealth goes back to people, either by free will (as in the case of charitable or foundations trusts) or because of the need to comply with government legislation (like India's CSR Act).

So I would consider CSR 1.0 as 'doing well and doing good'.

This means after one has done 'well' by amassing wealth, one turns to doing 'good', by setting up charitable trusts or foundations.

What I wish to propose is CSR 2.0; not replacing CSR 1.0 but complementing it and bringing a far greater impact by touching the lives of millions.

I call this as 'doing well by doing good'.

This means 'doing good' itself becoming a 'good business'.

But why should doing good be considered important? The answer is simple -- because rising inequality is one of the greatest challenges of our time.

Income inequalities, for instance, create access inequalities, which leads to social disharmony.

However, reducing income inequalities takes generations.

Can we do the magic of creating access equality despite income inequality? Yes, we can -- through CSR 2.0.

CSR 2.0: Doing Well by Doing Good

How do we achieve CSR 2.0?

We have to make a change in the way we do business, a change in which we the policy makers think, the way in which we do science, etc.

I will talk about the why, what and how of CSR 2.0 through which enterprises can 'do well by doing good'.

What do Indian businesses need to do to achieve CSR 2.0?

I propose that private sector can do well by doing good, if they adopt an ASSURED innovation strategy.

For me, ASSURED stands for the following: (Please click on the options below to know more)

Affordability is required to create access for everyone across the economic pyramid, especially the bottom.

'Affordability' obviously depends on the target consumer's position in the economic pyramid, the type of product, and its value and the opportunities it may help create.

But for the 2.6 billion people in the world earning less than US$2 per day, such affordable products cannot just be 'low-cost', but must be 'ultra-low-cost'.

Such extreme reduction targets require disruptive and not just incremental innovation.

Scalability is required to make real impact by reaching out to every individual in society, not just a privileged few.

Depending on the product, the target population may only be a few hundred thousand, or a few million, though in some cases, it may reach hundreds of millions.

We will cite examples of each.

Sustainability is required in many contexts; environmental, economic and societal.

In the long term, ASSURED innovation must promote affordable access by relying on basic market principles with which the private sector works comfortably, and not on continued government subsidies or procurement support.

The crucial importance of this feature is obvious: higher output, better competition (competition induced by market-oriented players and not intermediated by political actors), lower cost to taxpayers, and -- most importantly -- the critical market check that ensures inclusive products provide a good value to consumers and represent a genuine social undertaking.

It must be noted that the principle of long-term sustainable production does not negate -- rather helps to highlight -- the critical role of the government to establish and maintain a well-functioning innovation ecosystem capable of producing ASSURED innovations at a socially optimal level.

Universal implies user friendliness, so that the innovation can be used irrespective of the skill levels of an individual citizen across the economic pyramid.

Rapid means speedy movement from mind to market place.

Acceleration in inclusive growth cannot be achieved without speed of action matching the speed of innovative thoughts.

Excellence in technological as well non-technological innovation (such as business model), product quality, and service quality is required, not just for the elite few but for everyone in society, since the rising aspirations of resource-poor people have to be fulfilled.

Distinctive is required, since one does not want to promote copycat, 'me too' products and services.

In fact, we should raise our ambitions and make D as in 'disruptive', which will be truly game changing.

Achieving all the individual elements of ASSURED Innovation looks seemingly impossible but not necessarily so as we show now.

Let us ask some challenging questions:

- Can we make high speed 4G Internet available at 10 cents per GB, and make all voice calls free of cost -- that too in a large and diverse country like India?

- Can we make high-quality but simple breast cancer screening available to every woman, that too at the extremely affordable cost of $1 per scan?

- Can we make a portable, high-tech ECG machine which can provide reports immediately and that too at the cost of 8 cents a test?

- Can we make an eye imaging device that is portable, non-invasive and costs 3 times less that conventional devices?

- Can we make a robust test for mosquito-borne dengue, which can detect the disease on day 1, and that too at the cost of $2 per test?

Amazingly, all this has been achieved in India, not only by using technological innovation but also non-technological innovation.

ASSURED Indian Innovation

An exemplar in ASSURED innovation has been recently very successfully demonstrated by the Indian private sector.

One of India's early successes was the mobile revolution.

In the two decades from 1995 to 2014, about 910 million mobile phone subscribers were added -- the numbers are incredible in themselves, but especially so if you consider that this was 18 times the number of landline connections in 2006 when landline subscriptions peaked at 50 million.

The era of 'trunk calls' and ISD and STD booths had come to a definitive end.

Thanks to liberalisation, the private sector rose to the occasion and innovation flourished in devices, processes, and business models, among others.

It represented a joint victory for the public sector, for private enterprise and for people.

Despite India's impressive achievements, the benefits of the digital revolution were not shared by all, thus creating the 'digital divide'.

In spite of having a phone and a telecom connection, many could not afford to actually make calls.

Some of you may have heard of the Indian term 'jugaad' -- the Oxford dictionary defines it as 'a flexible approach to problem-solving that uses limited resources in an innovative way.'

So Indian jugaad came to the rescue and people began using 'missed calls' to communicate.

Many a parent, spouse and loved one signalled that they have arrived at their destination by giving a missed call to their anxious relatives and friends.

Restaurants that catered to students started 'missed call ordering' -- the students would place a missed call, and the restaurant would call them back and take their meal orders.

In fact, an entire marketing field called Missed Call Marketing was born.

Look around yourself today, and you will see that the situation has changed drastically.

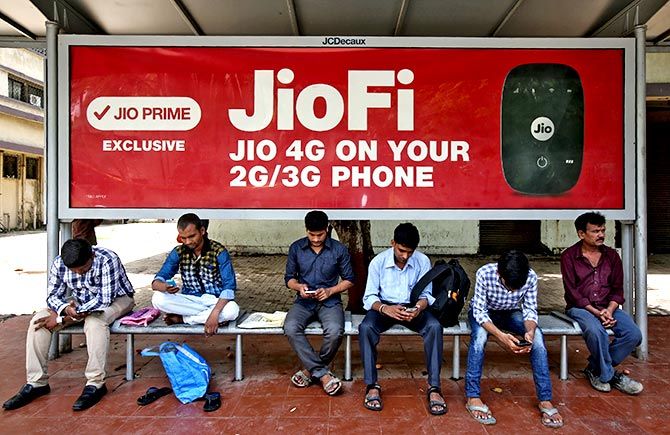

Competition in the Indian telecom sector reached a fever pitch in 2016 with the entry of Reliance Jio Infocomm Ltd, or Jio.

Today, millions of Indians enjoy the benefits of free voice calling and extremely affordable (10 cents per GB!) high-speed 4G Internet using their Jio connections.

Communication behaviours are changing across India as we speak, with the focus shifting from exchanging information to expressing emotion.

One incredible example is that of speech and hearing impaired people using video calls to communicate with each other in sign language.

Earlier, they were confined to using SMS and other texting apps.

This transformation has happened through myriad technological, product and business model innovations at Jio.

One of the most important innovations at Jio was its configuration.

Jio's greenfield LTE network is the first countrywide deployment of VoLTE or voice over LTE in India.

Jio has a 4G LTE network with no legacy 3G or 2G services, making it the only network in the world with this configuration.

This unique configuration allowed Jio to offer free voice calls to any network across the country -- at a time when it accounted for the majority of revenue for other telecom operators.

Jio also did away with national 'roaming charges', marking the first time in India's history that the length and breadth of the nation are truly connected.

There are many other product, business model, process and service innovations at Jio, which fulfil all the elements of ASSURED innovation.

Consider this: Jio fast-tracked Aadhaar-based eKYC (Know Your Customer) roll-out across thousands of stores.

This allowed SIM activation in under 5 minutes!

Before Jio, the activation process usually took hours if not days and racked up significant costs for the telecom companies.

Each one of its over 100,000 telecom towers erected was pre-fabricated and consumes 3 times less power than conventional towers.

Other equally important infrastructure development included 250,000 route kilometres of fibre optic cables laid, done using high-tech machines that laid the fibre deep underground with minimal surface disturbance just by drilling two holes.

The JioPhone is an Indian innovation -- by Indians, for Indians -- and is offered effectively free of cost to customers.

It is a feature phone that again fulfils all the elements of ASSURED innovation and allows users to benefit from access to the Internet.

I am convinced this will fast track access to high speed Internet across the country and empower each Indian to enhance their quality of life.

All these efforts have risen India's rank from #155 just one year ago to #1 today in global mobile Internet usage and India now has one of the most competitive telecom networks anywhere in the world.

More importantly, Jio has moved India from missed call to video call, a shift from jugaad to systematic innovation.

Jio is a true exemplar in ASSURED innovation.

You will say but this is doing good for the people of India.

But is Jio doing well? Is it making a profit? Yes, it is.

In the very second quarter of operations, it has turned profitable.

So this is indeed a case of doing well by doing good.

Dr R A Mashelkar's oration was delivered at the Australian National University and published by the Australia South Asia Research Centre at the ANU.

Dr Raghunath Anant Mashelkar served as director general, Council of Scientific & Industrial Research, and secretary, Department of Scientific & Industrial Research.

Over the years, he successfully led the process of the transformation of CSIR, the nation's premier scientific organisation, which manages 38 laboratories and 22,000 employees. CSIR is today one of the largest chains of industrial R&D labs in the world.

Dr Mashelkar played a pivotal role in framing India's national S&T policies in the post liberalisation era. He also contributed widely to restructuring and reforms in education, S&T institutions and industry, through the several committees he has chaired.

He set up the National Innovation Foundation to acknowledge and reward grassroot innovators.

As one of India's foremost chemical engineers, Dr Mashelkar has made path-breaking contributions in polymer science and engineering and in the engineering analysis of non-Newtonian fluids.

- Readers: You can write to Dr Mashelkar at ram@mashelkar.com

© 2025

© 2025