| « Back to article | Print this article |

Rediff Special: Design with a heart

Derek Lomas came to India as an intern, and fell in love. His Valentine to the country, Krishnakumar P finds, is high tech adapted to the low-end needs of the unprivileged.

Derek Lomas came to India as an intern, and fell in love. His Valentine to the country, Krishnakumar P finds, is high tech adapted to the low-end needs of the unprivileged.

At first sight, the glasses look like ordinary wraparound shades. Then you notice a tiny keyhole lens where the two eye pieces meet. Follow the wire that sprouts from the top of the bridge of the glass, and you find a tiny video recorder.

Derek Lomas is wearing what the media refers to as the 'James Bond glasses', 'X-ray glasses' and "glasses that can see through walls of houses".

What it really is, is a normal low-end camera mounted on his shades, that he uses to teach his 'design for development' class at the University of California in San Diego.

The course aims to develop products that will aid developing societies overcome existing handicaps and live better and the shades play a key role.

Lomas, who first came to India on a three-month internship and was so fascinated that he devised the course as a pretext to extend his stay, uses them to capture India in all its chaotic essence; the videos he thus shoots help students get a feel for the society for which they are designing products.

"Instead of explaining to them how Dharavi [the sprawling shantytown in the midst of metropolitan Mumbai that is Asia's largest slum] is, I just wear these shades and go for a stroll around the slums, so they get to see what it really looks like," Lomas says.

His students have used the insights thus gained to create education courses for rural/underprivileged Indian kids, found ways to tweak a $15 laptop, and created a mobile phone charger that is powered by a sewing machine.

When I enter his classroom, a lecture is already on. Guest lecturer Matthew Kam is speaking of incorporating educational software for mobile phones. I'm lost; a student senses my discomfort; Lomas tells me it is an advanced topic, not to worry. There is also, though this is as much excuse as reason, a problem with voice clarity I am in a virtual classroom on the Internet.

Lomas is in Bangalore; his class is in San Diego; Kam has logged on from Berkeley and I have joined in from my Mumbai office. For four months now, Lomas has been sitting in India, teaching a class of design students at UC San Diego.

He gives his students inputs on what developing societies need; the students respond by designing stunning products out of everyday things. He then tests the inventions out in Indian environments. Lomas says cognitive science and social design that engage a group of people has an inevitable social impact. "Every technology lends itself to development of a society. Thus, through technology, we can design societies. For example, something like the Nano (the Rs 100,000 small car conceived by the Tata group) is going to have a major impact on society."

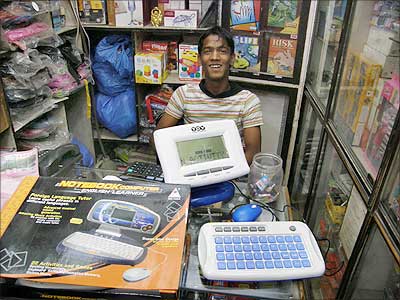

The challenges Lomas throws at his class, and the way they respond, underline the genius of simplicity. Like the time Lomas saw a $15 dollar laptop in a Mumbai toy store, in photograph above, which was marketing the gadget as an 'educational computer' that teaches English, spelling, mathematics and music. "In my limited experience, I found them too difficult to use and not much fun," Lomas wrote on his blog, where he picks his students' brains.

"These machines are not mere toys. They come with a programming shell. And the great thing about them is that they can be plugged onto a television. So what we wanted to do was bring in some sort of academic consideration. We are trying to figure out how to bring in local languages into the picture. After that, if we can generate low-cost cartridges with educational material, and also enable the kids to learn programming, it would be great.

"Imagine how by plugging this $15 device the living room changes into a learning room and the whole family is involved in the learning process," he says, and then signals his increasing understanding of how India works, when he grins: "Of course, only when the (television) serials are not on!"

The class has also designed a unique mobile charger and again, observation led to identification of a need, and that in turn to the solution. From the moment he landed in India, Lomas says, he has been amazed by the reach of the cell phone.

"From the milkman to the farmer, everyone has a cell phone. In fact, one of the first sights of India I had was a hawker showing a video clip on his cell phone to one of his customers, who then walked away with a bagful of tomatoes. I was tearing my hair out at the sight."

When he came to know about the lack of electricity in most parts of Maharashtra, he came up with an idea. "Why not design a mobile phone charger that will run on a foot-powered sewing machine, we thought."

The class went to work, and Lomas finally put together the device from a Nokia car phone charger, a bottle cap, and his elastic hair band. 'We don't know if this will ever get out of the lab, but we do know that there is a foot-powered sewing machine in nearly every village in India, that there is a lot of unmet demand for electricity, people can charge Rs 5 per charge, and that the poverty line in India is Rs 10,' he wrote on the blog.

The key to his ability to come up with ingenious solutions lies in how Lomas understands India itself. "I came to Mumbai in June 2007 on an internship with a mobile company, in a project that saw the mobile phone as a personal computer," Lomas says.

India as a society fascinated him. "Before I came to India I knew nothing beyond Akbar and Asoka. So I was psyched when I landed! The rickshaws were the first things that caught my eye. In the US, a 10-minute cab ride would easily cost $10. The same in a rickshaw works out to 50 cents. I was shocked to see the squat toilets. Most of all, I did not anticipate the diversity. I did not even know people spoke so many different languages. I found it to be a society where the fabulously rich lived alongside the ridiculously poor."

India and its perennial fascinations kept him back long after his internship. "After having spent three months in India as an intern, I did not want to go back to the US. I had to find a way to stay on. That was when I hit upon this idea. I thought it would be a great idea to teach design for development to students, while giving them a chance to try and implement their projects here at the ground level, in a developing country. I was basically trying to be their agent here in India," Lomas, a fine arts and design student himself, says.

Easier said than done: university officials who had greenlighted the proposal after a cursory glance were alarmed when reality sunk in -- a student was going to remotely teach a course with credits. "They sent me an e-mail two days before the semester was to begin. I saw the mail while I was in with friends in Goa.

"I, who have never ridden a motorcycle in my life, grabbed a bike and rode to a cyber café in a frenzy and got online." He managed, through instant messenger, to convince the university to approve his remote class and in the half year or so since, has more than repaid the university's faith.

In these six months, he has visited over 15 places across the country.

"A friend said the best place to celebrate Holi would be Banaras, so I went there," says Lomas, whose last six days in India were filled with train tickets and boarding passes in this order: Mumbai, Bangalore, Chennai, Kolkata, Banaras, Mumbai, San Diego.

What he found particularly fascinating, he says, is how people in India use technology. "In the US, texting is not very big. Same with music. And I am not sure if people even know what Bluetooth is. But the way people in India use all these things is ridiculous," he says adding that in that sense, he sees every country as a developing society.

"Our lifestyles in the West are not necessarily the be all and end all of life. Even we need to see ourselves as a developing society. If you drive out of most US cities, all you get are gas stations, strip malls, and highways. I want my class to be a two-way process. I want to take back some of the good things that I have learnt from India."

"When I began teaching the course, our aim was to find what real development is. We aren't any closer to an answer than we were when we started. But I am confident that we asked a lot right questions and worked at it," says Lomas, who is in awe over how rural societies in India were much happier than he thought they could possibly be.

"I couldn't make out how $75 of rice feeds a family for an entire year. A man makes Rs 4,000 a month and the family is happy. You can't see this in the United States," he says.