| « Back to article | Print this article |

Brookings Institution president and former US deputy secretary of state Strobe Talbott hopes his new book, Engaging India: Diplomacy, Democracy and the Bomb, a revealing and authoritative account of the most sustained talks between India and the United States prompted by New Delhi's surprise nuclear tests in May 1998 will be interesting to those who want to know more about India and "of some use to people who are genuine experts" on the subcontinent.

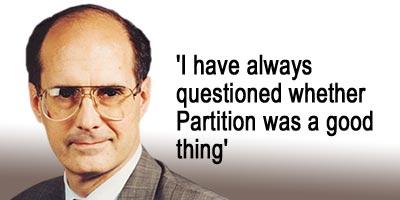

In his first interview after the book was released last month, Talbott, who was President Bill Clinton's pointman for the high-stakes diplomacy with then external affairs minister Jaswant Singh, said he enjoyed recounting this episode in the relationship between the countries "very, very much".

Talbott, who has written nine books and was a correspondent and columnist for Time magazine for 21 years, discussed his latest work with National Affairs Editor Aziz Haniffa of India Abroad, the Indian-American newspaper owned by rediff.com, in Washington, DC. Here's the second and final part of the exclusive interview:

Part I: 'Jaswant achieved more of his objectives than I'

Some critics believe there is an unquestionable pro-India bias in your book vis-à-vis Pakistan. That you sound like an Indophile.

Yes. I plead guilty to being an Indophile. It's a terrific country and immensely admirable, impressive case of an extraordinarily disparate group of people coming together to form not just a viable but a very promising modern State. I have personal as well as professional reasons to have admired at least some of the many, many good things about India.

I found during the course of the dialogue that the Indian side was, while being very, very tough, capable of pursuing a coherent policy not one the United States entirely agreed with, to put it mildly. But nonetheless it was a coherent policy and allowed us to move forward on a number of fronts.

By contrast with the experience I had with Pakistan during this period I have lots of good feelings about Pakistan and I have over the years had the opportunity to travel there as a journalist and as a government official and was always received with terrific hospitality and met some extraordinarily admirable people. But two points about Pakistan: I am quite candid about this in the book. I am one of those who have always questioned whether Partition was a good thing for the people of South Asia, and my reasons for that have to do with my belief as an American that a secular, pluralist democracy is the best form of government for most if not all people around the world and Pakistan has gone a different way.

There is a historical issue out there to be debated I respect the other view in this but there is also a contemporary issue, which is the extent to which Pakistan has been able to come together as a confident, modern State capable of carrying out straightforward, coherent policy, and the answer has been, not always, and I certainly experienced some of the 'not always' with them.

I found the Pakistani side while consisting of a number of fine individuals, Shamshad Ahmed being one, who was my principal counterpart the Pakistani government was constantly wrapped around its axle. It was wrapped around the axle of its insecurities about the United States where it stood with the United States and most of all, wrapped around its axle about India.

You have said on several occasions that you consider Jaswant Singh one of the most sophisticated individuals you have met, but in the book you seem to be definitely bothered by his advocacy of the Hindutva philosophy.

I wouldn't say bothered. I listened, very carefully, very respectfully and found myself sceptical about some of what I heard. [But] That wasn't only true of our dialogue on Hindutva, it was also true of our dialogue on non-proliferation and Pakistan.

In any case, on the question of Hindutva, do you believe all this is moot now with the defeat of the BJP and the advent of the Congress party? Is secularism safe, or do you still believe, as you have argued, that it should be a part of the US-India dialogue and on the agenda between the two countries?

I would say the latter. Just because the BJP is no longer the governing party, it doesn't mean it isn't still a powerful force in Indian politics and society. I realise that, like India, the BJP is a pluralistic phenomenon and there are different strains and different versions of Hindutva. But having paid a little bit of attention to other election results besides the national election result, the sentiment is still there and probably not limited to the BJP. Just as there are some aspects of the evolution of American society in politics that should be of interest and concern to all of our friends around the world, so the reverse is true with regard to India.

In Unfinished Business, you end with a call for the non-proliferation aspect of the relationship to be resurrected on the US-India agenda and bemoan the senate's killing of the CTBT, which may have effectively taken this off the table in terms of the bilateral agenda with India. There seems to be some sense of pessimism and a sort of a veiled warning that the Kashmir imbroglio could flare up again and there could easily be a return to the tension a few months before [former prime minister Atal Bihari] Vajpayee's olive branch to Pakistan, and hence the importance that this non-proliferation issue be returned to being a front-burner agenda priority?

I wouldn't call it pessimism. I would call it realism facing the facts. How many times have we seen, including during the life of the episode I describe in the book, where things seem all of a sudden to be going very well between India and Pakistan and then something untoward happens?

We remember Kargil very well. It was an extraordinarily dangerous and important moment. Would it be prudent for Indians, Pakistanis, Americans, or anybody else to dismiss the possibility of it happening again? No. It wouldn't be in the least prudent.

As for elevating the non-proliferation issue, I would put it differently again. I would say non-proliferation should have its own place of importance as the stakes are so high. It would be a mistake on the one hand to let non-proliferation overshadow other aspects of the relationship and prevent progress in other areas. But it would also be a mistake to sweep it under the rug.

Are you a non-proliferation ayatollah?

I am not any kind of ayatollah [laughing]. I am somebody who has spent, or misspent, an awful lot of my career thinking about problems posed by nuclear weaponry and the precariousness of countries that keep the peace between them through terror and I don't mean terrorism. I am talking about nuclear terror. I have that vantage point as I grew up during the Cold War. I vividly remember the Cuban missile crisis even though I was 16 years old or whatever. I hate to see good people and entire nations recreate that threat for themselves.

We are at an extremely precarious moment as a global community with respect to non-proliferation. What is very important for Indians that I talk to, to understand, is that by urging and expressing the hope that India will be a leader in the realm of non-proliferation, this isn't because of any lack of confidence in India's ability to be a custodian of its own military power. It is much more to do with the problem of precedence and example.

Because of what happened in the subcontinent in May 1998 and because of what has not happened since neither India nor Pakistan adhered to the CTBT or found a way to reconcile their positions with the NPT [Non-Proliferation Treaty] other countries like Nigeria, Brazil, never mind countries like Iran and North Korea, moved a lot closer to positions similar to the ones India and Pakistan took six years ago.

I hope sooner rather than later, India, for reasons based not on anybody pushing them around, but based on their self-confidence and wisdom, would look at the issue of their national defence in global terms. There are ways to do that, ways I detail in the last chapter, that would allow India to maintain the position it took in May 1998, even though I, as an American official at the time, thought that was a mistake.

What's your prognosis for US-India relations in the near term and long term, particularly now with a Congress party-led government?

Even if the BJP had been returned to power, the prospects would have been excellent because the fundamentals are much more close to being right now than they were six or seven years ago.

It would not matter whether it's a second Bush administration or a Kerry administration?

No. The nuances will be different, but the fundamentals of a sound US-Indian bilateral relationship will be there whatever the outcome of the American election.

If it's a Kerry administration, will you return to government?

I cannot conceive going back to government. I had a wonderful experience for eight years. I have more than gotten whatever curiosity or ambition in that regard I had out of my system. I have only been at Brookings for two and a half years. I want to spend a long time here. It's the greatest job I can imagine for myself at this point in my career.

Part I: 'Jaswant achieved more of his objectives than I'

Headline Image: Uday Kuckian

(Concluded)