| « Back to article | Print this article |

Brookings Institution president Strobe Talbott, former American deputy secretary of state, hopes his new book, Engaging India: Diplomacy, Democracy and the Bomb, a revealing, authoritative account of the most sustained talks between India and the United States prompted, of course, by New Delhi's surprise nuclear tests in May 1998 will be interesting to those who want to know more about India and "of some use to people who are genuine experts" on the subcontinent.

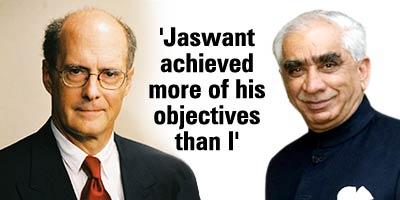

In his first interview after the book was released last month, Talbott, who was President Bill Clinton's pointman for the high-stakes diplomacy with then external affairs minister Jaswant Singh meeting 14 times in seven countries on three continents in one of the most intriguing political dramas in recent history said he enjoyed recounting this episode in the relationship between the countries "very, very much". In fact, he even remembered "vividly when I wrote the first sentence".

Before his tenure as deputy secretary of state (1994-2001), Talbott, a friend of Clinton who shared a room with him at Oxford for a while, was a correspondent and columnist for Time magazine for 21 years. He has written nine books, including The Russia Hand: A Memoir of Presidential Diplomacy, an account of US diplomacy towards Russia during the Clinton years.

In an exclusive interview, Talbott discussed his latest work with National Affairs Editor Aziz Haniffa of India Abroad, the Indian-American newspaper owned by rediff.com, in Washington, DC. Here's the first part:

What was your rationale for writing Engaging India? What do you hope it will achieve?

My principal purpose was to record and give my impressions of an episode that is of some importance because of what it ended up meaning to the quality and direction of the bilateral relationship. It is the second and I would firmly predict last book of this kind.

As a journalist, I used to write journalistic accounts of how policy and diplomacy are made. After eight years in government, I wanted to return to that genre only with the vantage point of somebody who is part of the process. I did that with the book on Russia that came out two years ago. I have done it here as those are the two most meaty and significant episodes I was involved in.

You are a prolific author, particularly on politics and diplomacy, not to mention on the likes of Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev, even translating the works of Nikita Khrushchev. But this is your first book on South Asia. How would you rate this book in your repertoire?

I put it differently. It's the first book not on Russia and the former Soviet Union. It's new in that respect. How would I rate it? It's my most recent brilliant book [laughs uproariously].

But what's a serious answer to that? It's old and new for me. It's old in that it's about diplomacy and about policymaking and, of course, in no small measure about nuclear weapons, which is also the subject I have written about since 1980 when my first book was about nuclear diplomacy between the United States and the Soviet Union, as were a number of subsequent books. In that sense, it's part and parcel of what I have done earlier.

While I have some claim to knowledge of the Soviet Union and Russia, I have no claim or illusions that I am an expert on India. The book was a chance to record an important episode in my education, which is to say my education about India. As a newcomer to the subject, even though I have been going there since 1974, I had much more intense exposure to many aspects of India over the course of the two-and-a-half years of dialogue. I thought it would be interesting to others who want to know more about India to see what I was able to learn through experience and it might even be of some use to people who are genuine experts.

How much did you enjoy writing it?

You and I, Aziz, are writers. We know writing is kind of a sublime torture or a torturous pleasure one or the other. But I enjoyed writing it very, very much.

I remember vividly when I wrote the first sentence, on a British Airways flight as it lifted off from Heathrow airport, bound for New Delhi in February 2003. I was on my way back to India for the first time since leaving the government. I had been giving the matter a lot of thought. I had retained a lot of my impressions and some of my notes, gotten access to other material, and been doing a lot of reading on Indian history and on the context. I had a lot of fun writing it. As much fun as one can have writing.

There seems to be a permeating acknowledgement throughout the book that Indian diplomacy and Indian diplomats got the better of their American counterparts. Is this a correct reading?

Yes. [But] I would like to amplify the point or qualify it. The line I use in the book is there's a famous adage by Dean Acheson, secretary of state in the Truman administration, that he never read a memorandum of a conversation in which the author comes off second best. This is a memorandum of a conversation in which the author comes off second best. The person who comes off best is Jaswant Singh.

Jaswant Singh had some objectives. He achieved more of his objectives than I achieved of mine in the realm of non-proliferation and the benchmarks and so forth. Though one reason I would judge the experience to have been mutually beneficial to the United States and India is that there was a larger agenda that was implicit early in the dialogue and explicit as the dialogue went on, which was to change the quality of the US-Indian official relationship. There we both succeeded.

Now, the reasons why the Indian side was able to accomplish more of its objectives, which I would say were, in a sense, from our standpoint, negative, ie, preventing things we wanted to persuade India were in its interests to do. It was certainly in no small measure because of Jaswant Singh's qualities as a human being and a diplomat and a statesman and because of the coherence and firmness of the Indian government at that time. That was contrasted to the American side where you had a very real split between the executive branch and the legislative branch. But I would argue to this day, and do in the book, that what the United States was urging India to do with respect to its nuclear weapons programme was not contrary either to Indian national interests or to the Bharatiya Janata Party's policy as we understood it at that time. I hope some of the issues left unresolved by the dialogue may be resolved in due course.

In some ways, the story is ongoing. In fact, the last chapter of the book is called Unfinished Business. Perhaps as a result of diplomacy underway, particularly between India and Pakistan, some of the issues might come up in future in a way that will make them more soluble than they were when I was working them.

Was there a misreading or misperception on your part and that of your diplomatic colleagues and Washington in general after the Pokhran tests that India would be on the defensive after international condemnation, while in reality India was very much on the offensive in the sense that it had declared publicly that it was now a nuclear power whether you guys liked it or not?

I would put it a little bit differently. First of all it's important for your readers to understand what you know very well, having read the book and having followed the story, and that is, what the United States was asking India to do, starting May-June 1998 and right up to the last day of the Clinton administration, was not, repeat not, to retreat or backtrack or undo what it had done.

You know this metaphor the image of the genie in the bottle is constantly used. If we had it within our power to put the genie back in the bottle, of course we would have done that. But there was never any thought that India was going to be taking one step backward with regard either to having tested or having proclaimed itself to be a nuclear weapons state. What we proposed to India in the course of the dialogue from the beginning was ways of moving forward, ways of increasing the safety of the country, then of the subcontinent, and of the world.

The specific issue that got the most attention diplomatically and publicly was the CTBT [Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty]. It was on the CTBT that the American government was disadvantaged as the next couple of years unfolded, not because of anything India did, but because of what our senate did.

I am trying to come to terms with your question about whether we miscalculated. We knew India was dead earnest about never turning back. We knew the international opprobrium there was a lot of it which came down on India's head at the time would dissipate over time. We knew our sticks, as they were, were of limited utility and by the way, a number of those sticks, the sanctions, were a matter of American law. It wasn't a matter of the executive branch saying what can we do to hurt India. Nobody in the American government wanted to hurt India. We had to carry out the law. We wanted to make sure the Indian side took account of the broader consequences of what it had done and looked for ways with us to ameliorate the issue.

Would you say that much of the administration's negotiating power was taken away by the fact that the Republican-controlled Senate rejected the CTBT?

Yes, absolutely. Absolutely. Now, of course, as readers of the book will know and Indians will remember, the problem was not with domestic politics on the American side. There was also a problem with domestic politics on the Indian side. There were long periods of time when for electoral and other reasons the government with whom we were carrying out the dialogue had its difficulties and had to look over its shoulder at Parliament and so forth.

You state clearly that the likes of [then defence minister George] Fernandes and [then foreign secretary K] Raghunath misled the United States, but that it was not deliberate. That they were so out of the loop.

Well, I am basically a charitable guy. I am assuming George Fernandes and Foreign Secretary Raghunath were not deliberately misleading us, but there's no question that Americans Bill Richardson, Tom Pickering, Rick Inderfurth, and others who dealt with those two gentlemen at that time came away with the distinct impression that what happened was not going to happen. As best I have been able to reconstruct it and here, by the way, I have been relying not only on things I heard and know from myself, but also what other learned people have written since.

Headline Image: Uday Kuckian

Part II: 'I have always questioned whether Partition was a good thing'