The International Court of Justice was last a battleground for India and Pakistan nearly 18 years ago when Islamabad sought its intervention over the shooting down of its naval aircraft.

On Monday, the ICJ, which is the United Nations’ principal judicial organ, is holding a public hearing at the Great Hall of Justice housed in the Peace Palace at The Hague in Netherlands where the two countries will be asked to present their case over the contentious Jadhav issue.

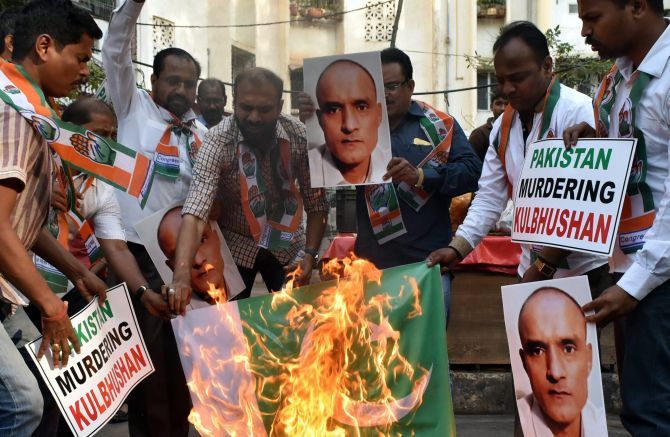

India on May 8 moved a petition before the UN body to seek justice for Kulbhushan Jadhav, 46, alleging violation of the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations by Pakistan after its 16 requests for consular access to the former naval officer was consistently denied.

A Pakistani military court awarded death sentence to Jadhav last month for alleged espionage and subversive activities. Pakistan has also not responded to the request for visas applied by Jadhav’s family. Jadhav was arrested on March 3 last year.

The previous case related to shooting down of Pakistan’s maritime reconnaissance aircraft Atlantique by the Indian Air Force in the Kutch region on August 10, 1999, killing all 16 naval personnel on board. Pakistan claimed the plane was brought down in its air space and sought $60 million in damages from India for the incident.

A 16-judge bench of the court on June 21, 2000 voted 14-2 to dismiss Pakistan’s claim. The decision was announced by bench president Gilbert Guillaume of France at a public sitting. The verdict was final and there was no appeal.

The ICJ found that it has no jurisdiction to entertain the application filed by Pakistan on September 21, 1999.

Public hearings in the case titled ‘Aerial incident of August 10, 1999 (Pakistan vs India)’ lasted four days ending April 6, 2000. Arguments centred on the court’s jurisdiction in the case which had to be determined before its merits could be considered by the 16 judges.

The Atlantique case was ousted by the ICJ on the issue of jurisdiction and not on merits. Both parties had agreed that the question of jurisdiction would be decided first and only then would the issue of merits be taken up.

Guillaume said the court would first have to decide whether it had the jurisdiction to go into the case as contended by New Delhi after the Indian delegation led by the then Attorney General Soli Sorabjee, raised preliminary objections to its jurisdiction.

Pakistan opened the first round of oral arguments, India replying them, and then Pakistan following with its second round, with India making its response thereto.

India argued that the court did not have jurisdiction in the matter, citing an exemption it had filed way back in 1974 to exclude disputes between India and other Commonwealth states, and disputes covered by multilateral treaties.

Sorabjee told the court that Pakistan was ‘solely responsible’ for the incident and Islamabad must ‘bear the consequences of its own acts’.

Pakistan’s Attorney General Aziz Munshi had sought a speedy resolution, saying its application had to be concluded quickly so that it did not remain an irritant in Indo-Pak relations.

Pakistan had also sought to politicise the case by referring to the Kashmir issue, the Kargil conflict, Indo-Pak relations and alleged motives for the shooting.

Pakistan wanted the court to intervene while India was opposed to its assumption of jurisdiction on the basis of Islamabad’s application.

It urged the court to ‘dismiss the objections raised by India and accept its jurisdiction’.

India maintained that none of Pakistan’s arguments is ‘sound’ and does not provide a basis for invoking the court's jurisdiction.

Sorabjee expressed happiness with the court’s verdict.

“We are very happy. The court has accepted all our contentions,” he had said.

Former Supreme Court judge B P Jeevan Reddy and Pakistan’s former Attorney General Syed Sharifuddin Pirzada were co-opted into the bench as ad hoc judges.

As per ICJ rules, when it does not include a judge possessing the nationality of the state party to a case, the state may appoint a person to sit as a judge ad hoc for the purpose of the case.

The court also recalled that its lack of jurisdiction does not relieve States of their obligation to settle their disputes by peaceful means.

The choice of those means admittedly rests with the parties under Article 33 of the UN Charter, it said, adding, they are nonetheless under an obligation to seek such a settlement, and to do so in good faith in accordance with the Charter.

As regards India and Pakistan, that obligation was restated more particularly in the Simla Accord of July 2, 1972. Moreover, the Lahore Declaration of 21 February, 1999 reiterated ‘the determination of both countries to implementing the Simla Agreement’, it said.

Accordingly, the court reminded the parties of their obligation to settle their disputes by peaceful means, and in particular the dispute arising out of the Atlantique incident in conformity with the obligations which they have undertaken.

India’s External Affairs Ministry while hailing the verdict especially welcomed the court’s positive observations on the principles enunciated in the Simla agreement and Lahore Declaration as the basis for an Indo-Pak rapprochement.

Through its comments, the court has vindicated India’s stand on these landmark agreements that are the very cornerstone of India-Pakistan relations, a ministry spokesman had said.

© 2025

© 2025