| « Back to article | Print this article |

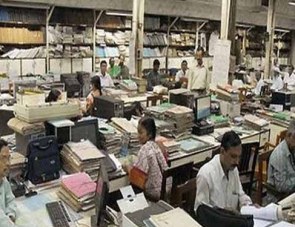

Indian officialdom enjoys well over a week of Sundays every month. That is, a minimum of 120 days a year, not counting casual, medical and other contingency leaves, says Sunil Sethi

Indian officialdom enjoys well over a week of Sundays every month. That is, a minimum of 120 days a year, not counting casual, medical and other contingency leaves, says Sunil Sethi

Stands the clock at 10 to nine? And are we ready for holiday time? It is and we are. There can hardly be a bureaucracy in an emerging economy that is as addicted to the idea of squeezing time off at taxpayers' expense.

A cursory calculation on an Indian calendar shows that there are 39 holidays in the year - national, religious and regional. District collectors in the hinterland have the authority to declare a few more for purely local events, such as a temple procession, celebrating a Sufi or Christian saint's day, or a festival such as the ‘Jor mela’ in Punjab.

When Rajiv Gandhi came to power in 1984, he broke from the norm of a government holiday on second Saturdays and declared all Saturdays as off days for officials ‘to renew their links with nature’.

When you add them all up, Indian officialdom enjoys well over a week of Sundays every month. That is, a minimum of 120 days a year, not counting casual, medical and other contingency leaves.

On my calendar, gifted by a government department and colour-coded in two scripts between official and optional holidays, June is the only month that looks sadly bereft of a public holiday. But then, it must be remembered, this is when schools, courts and colleges shut down in much of the country, and government employees take off for what continental Europeans call Les Grand Vacances.

Last year, there were dark mutterings and muffled protests (including from the Supreme Court's Bar Association) when the outgoing chief justice, R M Lodha, slashed the apex court's annual vacation from 10 to seven weeks.

He cited the humongous pile-up of pending litigation as the main reason, arguing that in a year the Supreme Court worked for only 193 days, the high courts for 210 days and trial courts for 245 days a year.

Still, some judges continue to perceive slights, where none were intended, when summoned to work on a religious holiday. Justice Kurian Joseph of the Supreme Court expressed his ‘deep hurt’ and ‘shock’ to Chief Justice H L Dattu for being dragged away to a judges' conference on Good Friday.

His pained missive reads not so much a succinct expression of dissent as a rambling moan at being summoned on "holy days when we have religious ceremonies and family get together as well [sic]".

His colleague judge Vikramjit Sen joined his protest. Interpreting it as a case of majoritarian prejudice, would such a conference be held on Holi, Diwali or Eid, they asked? To his credit Dattu overruled their objections, arguing that institutional interest was greater than individual interest and a balance was necessary between official and family commitments.

Holiness is Bharat Mata's middle name, but even by her exacting standards of piety, in my opinion, the miffed judges are taking the argument a little far. If the toiling farmer, the floor-swabbing housemaid, the 24x7 media and millions of commercial and professional establishments were to down tools on every religious holiday, the country would be plunged in crisis.

In her book Punjabi Parmesan: Dispatches from a Europe in Crisis, the journalist Pallavi Aiyar gives piquant examples of how the creeping lassitude and welfare-induced leisure economies of the West are hit by India's and China's driving work ethic.

Like our civil servants, swathes of Europe's workforce are often on holiday. Even when offered large sums of money, a plumber or gardener in Brussels would refuse to interrupt their weekends or required booking months in advance.

Was it any wonder that Sikh immigrants were running Italy's farms, the Chinese were buying up French vineyards and in Antwerp, devout temple-building Jain merchants held a tight grip on the diamond trade?

If their salaries, perks and ceaseless hunger for holidays were directly linked to productivity, the bureaucracy and judicial administration might improve its glacial pace of doing business. (Bank holidays, for instance, are capped at 15 a year by the department of economic affairs.)

Two recent pay commissions have recommended that national holidays be restricted to three a year (Republic Day, Independence Day and Gandhi Jayanti) and government employees could choose eight more according to their religious preference. Fearing a backlash, no government has had the guts to implement this simple reform.

It took former chief justice Lodha nearly 50 years to enforce a cut back in the time-dishonoured tradition of a 10-week vacation for the Supreme Court.

And for his successor to stand up and say that working on a religious holiday was a matter of collective convenience, not personal offence. After all, most Indians manage to combine both without complaint.