Several former colleagues say Arvind Kejriwal is undemocratic. But his loyalists stand stoutly behind him

A senior Bharatiya Janata Party leader thinks Arvind Kejriwal is probably the best communicator in Indian politics today, better than even Narendra Modi in his ability to connect with the common man. The Aam Aadmi Party chief’s opponents are far more charitable in their private assessment of him than several of his current and former colleagues. Anna Hazare is unable to trust Kejriwal, former diplomat and AAP founding member Madhu Bhaduri has slammed the party leadership as a bunch of “misogynists”, Kiran Bedi thinks Kejriwal is “toxic” in his negativity, Yogendra Yadav has questioned his “supreme” model of leadership and Shanti Bhushan feels he has gone astray.

Bhushan, a founding member of AAP, put the spotlight on Kejriwal’s people skills last week when he said Bedi, the BJP candidate, would make a good chief minister for Delhi. Many enthusiastic supporters like Vinod Kumar Binny, Shazia Ilmi and Capt Gopinath have quit AAP in the last few months.

Some are upset but have refrained from rocking the boat. One of them is senior lawyer Prashant Bhushan who is miffed that his concerns about some candidates for the upcoming Delhi elections were ignored by the party. And a few like Yadav have buried the hatchet after expressing their dissent. If BJP’s decision to press its entire leadership into the Delhi campaign is any indication, none of this has dented Kejriwal’s popularity. Surveys suggest he is very much in the race to become Delhi’s chief minister. But the question remains: why does Kejriwal upset friends?

The epithet Kejriwal’s detractors frequently use to describe him is “dictatorial” - and this is what drives people away. Kejriwal’s friends give a different spin to it. If they are to be believed, the departures are nothing but the weeding out of opportunists, fence-sitters and agents of other political parties.

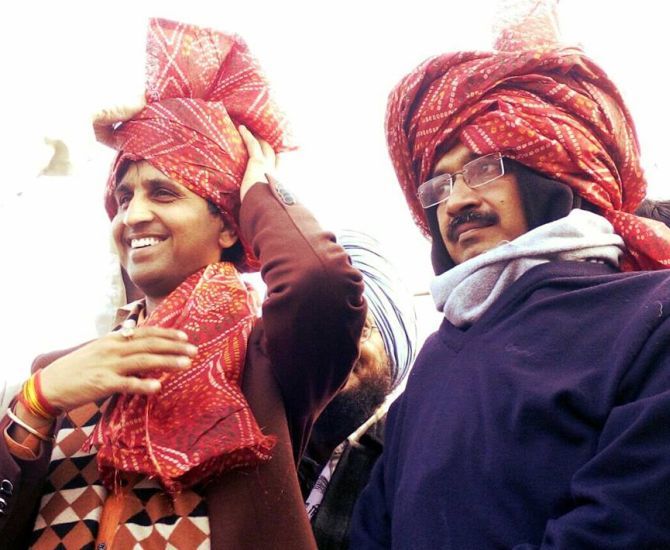

Kumar Vishwas, an old aide, says people like former Army chief VK Singh and Bedi were embedded into the India Against Corruption movement to “misguide” Anna to part ways with Kejriwal. “Singh was a plant of the BJP and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh in the movement and he was successful in his attempt to finish it.”

The reference is to the fourth fast undertaken by movement leaders at Jantar Mantar, New Delhi, on July 25, 2012. The health of Kejriwal and his Man Friday, Manish Sisodia, was deteriorating. As many as 22 close associates, including Singh, urged them to a solution to break their fast and take the political route.

On August 3, Kejriwal formally announced the decision to form a party. By all accounts, this started his rift with Anna, who did not want to get into electoral politics.

According to one account, Team Anna held a meeting of about 40 people associated with the movement and, following this, two groups were formed: one led by Kejriwal that would take up politics and the other, remaining non-political under Anna. “There was a joint statement which made it clear that the goals of the two groups would be the same but their directions would be different. It is strange how Anna portrayed a completely different version to the media,” says a founder member of AAP who was present in that meeting.

That is when another relationship fractured. “Bedi was of the view that we could not fight with two parties but our efforts should be to contest only against the Congress,” says AAP strategist Ajit Jha. Bedi, of course, now leads the BJP charge in Delhi.

Soon thereafter AAP was born. In December 2013, it launched a high-decibel campaign for the Delhi assembly elections. It put up an impressive show, but fell short of the majority. AAP formed the government with the Congress’s support but Kejriwal resigned after 49 days and much public tamasha. It was now time for the general elections. The core AAP team read the situation differently. At a meeting of the political affairs committee, AAP’s top decision-making body, there were prolonged discussions on whether the party should contest the Lok Sabha elections with full force or fight a limited number of seats. Yadav, the party ideologue, felt the party should try to get a national footprint. Kejriwal was sceptical but was convinced by Yadav and others to contest in almost every state.

The infighting began when tickets were distributed. Binny, one of its Delhi MLAs, demanded the ticket for East Delhi. His request was denied on the grounds that no MLA would contest the general elections.

Binny turned rebel, shouted anti-Kejriwal slogans and held an indefinite fast which he called off within four hours. This led to his expulsion from the party. (Binny is contesting the Delhi elections against Sisodia, on a BJP ticket.) What riled Binny was that Rakhi Birla, another AAP MLA, was given the ticket to contest from Delhi, and that Kejriwal himself fought from Varanasi. The party had reviewed its decision just before Kejriwal filed his nomination from Varanasi. The ticket distribution caused more exits: Maulana Maqsood Ali Kazmi, Ashok Agarwal and Ashwini Upadhyay.

More fissures came out after the elections, in which AAP won just four seats -- all from Punjab. Ilmi, the young, Muslim and woman face of AAP, let it be known that she wanted to contest from one of the seven Delhi seats but was forced to try her luck from Ghaziabad in Uttar Pradesh. She has now joined BJP.

The biggest blow to Kejriwal’s work style came when an exchange of letters between Yadav and Sisodia reached the media. Yadav, who offered to resign from the political affairs committee, took a dig at Kejriwal in the correspondence. “There is a difference between a leader and a supremo. Love and affection for a leader often turns into a personality cult that can damage an organisation and the leader. This is what appears to be happening to our party,” he wrote. “Major decisions of the party appear to, and indeed do, reflect the wishes of one person; when he changes his mind, the party changes its course of action; proximity to the leader comes to substitute organisational roles and responsibilities.”

In his rebuttal, Sisodia threw the blame back at Yadav. “It is shocking that you have alleged Kejriwal doesn’t listen to the political affairs committee’s suggestions. As long as Kejriwal listened to you, he was nice, but now he is not,” he charged. “Kejriwal was against fighting the Lok Sabha polls and just wanted to concentrate on Delhi. But it was you and a few other members who wanted to fight. The result is now in front of us… Do you want to finish off the party? Do you want to win your personal battle with Naveen (Jaihind) or do you want to finish off Kejriwal?”

The last line exposed another rupture within AAP. Jaihind, the head of the party in Haryana, after the loss in the general elections, had complained that Yadav had selected a few undeserving candidates and offered to resign. Concerned at the public rift, Kejriwal called a meeting and convinced both Yadav and Jaihind to stay on.

Kejriwal likes to play down these differences. “In a family there are small conflicts that get sorted out. Similar is the case in our party,” he said in November. His friends contest the allegation that AAP is undemocratic. “Whoever has left the movement has done so because of personal greed. These are lifelong fights and people tend to become impatient. Ilmi blames the party for lack of inner democracy but she has joined a party (BJP) which has no democracy at all,” Vishwas says.

Loyalists like Vishwas, Sisodia, Yadav and Prashant Bhushan have stood by Kejriwal -- so far. “I don’t care about the leadership skills of Kejriwal. I am just concerned about those who continue to stand for issues such as the Jan Lokpal. Till the time AAP follows these key issues, I will be a part of it,” Vishwas adds.

But the controversies refuse to die down. In the forthcoming Delhi elections too, there is visible dissent in the top leadership over ticket distribution. Prashant Bhushan was unhappy with 12 candidates and alleged that these contestants were indulging in wrong practices during their campaigns. However, the party cancelled the nomination of only two candidates. Bhushan is silent on whether he is upset with Kejriwal or not.

It is also clear that not all parts of AAP move in the same direction. At an internal meeting a couple of months before the 2013 Delhi polls, Yadav said the nascent outfit should project a “collective leadership”, not any individual.

Everybody, including Kejriwal, agreed. But the thousands of posters and banners that came up across Delhi 24 hours later showed only Kejriwal. In the next meeting, Kejriwal and his associates were accused of reneging on the agreement. Kejriwal’s lieutenants explained that party supporters had put up the posters and banners in a “spontaneous” gesture, and neither Kejriwal nor those close to him had anything to do with it. Former party insiders now claim it to be the handiwork of Sisodia. “In the initial days of the anti-corruption movement, Kejriwal would describe Sisodia to some of us as his djinn, somebody who fulfilled his master's every wish,” an old associate of Kejriwal says.

Sisodia is the preeminent leader of the small group that runs AAP, Kejriwal being the undisputed leader. Another prominent member of the coterie is Sanjay Singh. While Vishwas is trying to make a comeback, former journalist Ashutosh is also looking to rejoin the bandwagon. The clique includes several backroom boys like Pankaj Gupta. Leaders like Yadav and Prashant Bhushan, while consulted on important matters, work on the margins of the coterie. The coterie has not only upset quite a few people but has also taken decisions that boomeranged, including the ill-advised dharna outside Rail Bhavan just days before Republic Day last year.

According to one insider, Kejriwal and Sisodia drew ridicule for disrespecting the sanctity of the Republic Day and the Constitution. Kejriwal and his coterie didn’t know that the entire parade zone, including the area near Rail Bhavan, is taken over by the armed forces days before the parade. The team panicked when an army officer came to the protest site and asked them to vacate the spot, or else they would be bundled into Army trucks and driven away. They were saved the embarrassment only when the United Progressive Alliance government gave them an honorable exit.

Kejriwal has been faithful to people loyal to him. During the Lok Sabha elections, he kept his faith in Sanjay Singh despite complaints that the man from Uttar Pradesh had distributed tickets to people from his community, the Thakurs. Anna, during the Jan Lokpal movement, wanted to axe a member of the Kejriwal team but couldn't do so.

What does the common man make of these disputes and allegations? That will be revealed once the results of the Delhi polls are out on February 10.

© 2025

© 2025