The BJP government in Uttar Pradesh battles its own and Opposition over the community’s ‘victimisation’ and alleged preference to the Rajputs.

Radhika Ramaseshan reports.

Devmani Dwivedi has become a spokesman for Uttar Pradesh’s Brahmins.

A first-time legislator from Lambhua (Sultanpur), 55-year-old Dwivedi won on a Bharatiya Janata Party ticket, but claimed he did not think twice before raising his community’s “concerns and anxieties” over the Yogi Adityanath government.

He is among the 58 Brahmin MLAs in the BJP.

“Nobody takes up our issues. We aren’t even being offered churan chatni (a candy). The BJP should realise that without the Brahmins, it is like Ramlila without Ram,” said Dwivedi.

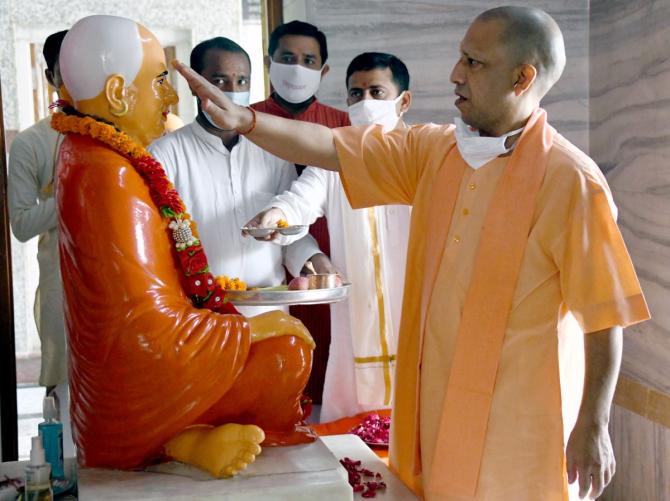

With a Rajput as chief minister, the Brahmins monitored every move relating to their representation in the government that Adityanath made.

With reason, argued Dwivedi.

A study on the 2017 Assembly elections by the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies assessed that 82 per cent of the Brahmins voted the BJP.

Dwivedi noted that despite being numerically smaller, the Rajputs (an estimated 7 to 8 per cent as against 10 to 12 per cent Brahmins) had five Cabinet ministers, including the CM, while the Brahmins had only four ministers.

The perception that Adityanath encouraged his clanspersons was reinforced by two developments: His government scrapped the holiday on Parashuram Jayanti and it packed Rajputs in institutional domains.

Parashuram is regarded as the sixth incarnation of Vishnu.

Mythology has it that although he was born in a Brahmin family, he displayed warrior-like traits.

To avenge the murder of his father by a Rajput, he killed all the male Rajputs 21 successive times (for each time, their wives survived and birthed new generations).

Although Parashuram is not revered in the pantheon of Hindu deities on a par with Ram, Krishna and Shiva, the more partisan Brahmins adopted him as a triumphal symbol.

In the heartland where legends easily segue into beliefs, the Brahmin-Rajput fault lines that surfaced in the Adityanath regime served as a feint to resurrect the Parashuram iconography.

Abhishek Mishra, Samajwadi Party national secretary, promised to raise a 108-foot statue of Parashuram under the banner of the Bhagwan Parashuram Chetna Peeth, if his party returned to power, while former Congress MP, Jitin Prasada -- who launched a Brahmin Chetna Parishad -- demanded the reinstatement of a holiday on the warrior-rishi’s birthday.

Amarnath Mishra, Lucknow-based president of the Ayodhya Sadbhavna Samanvay Samiti and votary of the Brahmin identity, questioned the Parashuram political adoption and said: “Whose prestige is one enhancing by constructing a statue? It will heighten the tensions between the Brahmins and the Rajputs.”

Mishra contended that the root of the Brahmin “victimisation” was the community’s involvement in land disputes and family feuds over properties.

“It is because the Brahmins gave up the traditional shaastra (sacred scriptures) and picked up shastra (weapons)," he said.

The “weaponry” association was personified in the encounter killed of Vikas Dubey, the Kanpur criminal who had murdered eight policemen when they went to arrest him in July.

There were opposing reactions from the Brahmins but the episode fuelled the “victimisation” narrative.

“Dubey defamed the Brahmins because the cops he gunned down were all Brahmins,” said Mishra.

Prasada of the Congress maintained, “It’s not about one Dubey. There’s been a spate of murders: The victims are mostly Brahmins, and there’s no help from the government.”

Prasada, who’s been touring on a Brahmin Chetna Samvad, claimed: “It’s not about votes but the sense of neglect that the Brahmins feel. The community has been painted as criminals. My information is that the Brahmins are leaving their villages in West UP.”

The flashpoint was a question listed by the BJP’s Dwivedi in the assembly, seeking answers on the killing of the Brahmins, why they felt insecure, and how many were issued gun licences since 2017.

The UP government reportedly sent a missive to the district magistrates, seeking data on how many Brahmins received licences.

The letter was withdrawn but Dwivedi said his question, that he did not pull back, remained in abeyance.

“I will not let go of it,” he emphasised.

However, none of those fighting for the Brahmins had a database on the number of murders and other forms of repression that engendered a sense that the campaign for the community might be underpinned more on quasi fiction and hearsay than facts.

For instance, Mishra of the SP said: “When we were in power, we did a lot for the Sanskrit vidyalayas. I hear the government is going to block the funds for them.”

A BJP MP conceded that despite the prevalence of “half-truths” in the Brahmin-as-victims account, Adityanath was “partial” towards the Rajputs.

“The Gorakhnath math of which he is a custodian is a Rajput bastion. It has no place for another community. His politics is influenced by that kind of casteism,” the MP said.

However, Harshvardhan Bajpai, Allahabad North MLA of the BJP, thought the issue was “blown out of proportion”.

“The Opposition isn’t serious about keeping law and order. They see it as politics to score brownie points. The Brahmins are known as the BJP’s motherboard. So why would we target our core voters?” asked Bajpai.

Even the SP’s Mishra conceded it was pointless to chase a single agenda of winning over one community.

“The Brahmins generally vote as a bloc, if they want to bring down a government. Getting 80 per cent of their votes is a long haul," he said.

© 2025

© 2025