'Studying History, we come close to all of the messiness of human life -- we understand what motivates people, what makes them get along or go to war, what dreams they had for themselves and their futures.'

Sunil Amrith, professor of South Asian Studies and Professor of History at Harvard University, is one of the 24 recipients of the most prestigious MacArthur Genius Grant that was announced recently.

In the second part of an interview to Rediff.com's Archana Masih, the 38-year-old historian emphasises why history is more important now than ever before.

In India, the debate is about whether to deport or provide refuge to the Rohingyas.

Drawing from your understanding of migration, how do you view India's stance?

Do you think India should give the Rohingyas refuge?

Does the background of India's shared history with Burma hold any pointers in this situation?

I think India should live up to the noblest of its political traditions in extending refuge and hospitality to the Rohingyas who are suffering the most intense persecution of any community in recent history.

India and Burma have a long shared history, and political decrees cannot undo that.

Mobility across that border region between India, Bangladesh and Myanmar long predates the borders themselves. But even from a standpoint of self-interest, a humane resolution to the Rohingya crisis ought to be in the interests of every State in the region.

One of the most insightful observers of the crisis is the Straits Times journalist Nirmal Ghosh, who has pointed out that the crisis threatens to embroil the whole region.

Do you feel history is becoming more and confined within the boundaries of countries to the detriment of shared histories between regions, cultures and peoples that go beyond the borders of state and country?

I do and I am less optimistic now than I was a few years ago about the possibility of bringing these shared histories to a wider public. But if there is an optimism that comes from studying the past, it is a sense that 'this too shall pass'...

I can only hope that is true of the rising tide of intolerance, violence, and authoritarianism that we are witnessing around the world.

If a young student were to ask you why s/he should opt to study History, what would your response be?

First and foremost because it is exciting.

Studying History, we come close to all of the messiness of human life -- we understand what motivates people, what makes them get along or go to war, what dreams they had for themselves and their futures.

It confronts us with the biggest question: What is universal and shared between human beings across time and space, and what is specific to particular societies or cultures or epochs?

History also teaches skills that I think are more important than ever in this age of information overload: How to sift different accounts of an event to come up with a complex picture (how to identify historical equivalents of 'fake news'!); how to work with lots of different kinds of evidence, from manuscripts to statistics; how to tell stories in a way that is compelling but true.

What was the seed behind writing Crossing the Bay of Bengal and exploring migration across the Bay?

I think there were many seeds of that book, some of which only became clear with hindsight.

Having grown up in Singapore, to parents who were migrants from India, migration was always a part of my life.

I come from a relatively privileged background, and I think that as a young person I took migration for granted as somehow 'normal' -- it was later that I realised how often migration is a traumatic experience, accompanied by constraint and violence and loss.

I spent a lot of time in India as a child visiting family during school holidays, and I think it was a matter of intuitive common sense to me that India, especially Tamil Nadu, and Southeast Asia were deeply connected.

When I started studying History at university, it dawned on me that there was very little acknowledgement of those connections. Books on Indian history very rarely had anything to say about Southeast Asia, and vice versa.

More immediately, my book also comes out of a much broader movement in scholarship: A movement towards writing histories that did not take national boundaries for granted.

I was inspired by my teachers at Cambridge, by the work of many of my contemporaries in the field, and also by scholars who focus on an earlier period (like Sanjay Subrahmanyam), to think about how movement, migration, and cultural flows have always crossed imperial or national borders.

In many ways, we misunderstand the past by projecting back in time our twentieth century territorial boundaries. This is not to say that borders are unimportant -- quite the contrary.

But we need to understand how borders (including political borders between majorities and minorities, insiders and outsiders) were themselves a product of the same forces that enabled large-scale migration.

He is the author of three books and his focus of research is global migration.

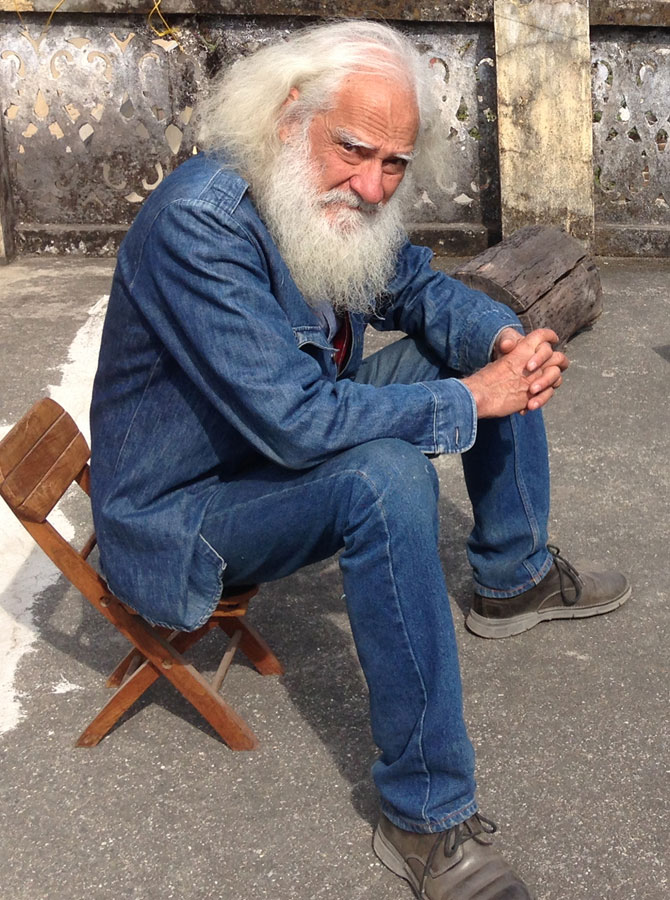

Photograph: Kind courtesy, CC-BY. Credit: John D & Catherine T MacArthur Foundation

Where and how did your interest in History begin, shape and take root?

I think my interest in History took shape when I was a teenager in high school in Singapore. I had wonderful history teachers at school, who made History come alive for me.

Living in Singapore, and having the opportunity to travel to other parts of Southeast Asia, I turned to History as a way to help me understand the world around me.

Only History, I realised, could explain why countries as close to one another as, say, Malaysia and Cambodia, could be so different.

Also, I came to political awareness at a time of momentous change around the world, and that too sparked my interest in the past: I was 15 in 1994, the year that saw the first democratic elections in South Africa, and the Rwandan genocide -- my window onto the world at that age was often the BBC World Service, which was a fixture in our household.

How much time did you spend travelling through India for the book?

I spent a lot of time travelling through India for the book. A lot of the archival material I used in the book were in the National Archives of India in Delhi, as well as the Tamil Nadu state archives.

I was fortunate to spend some time browsing the amazing collections of pamphlets and other materials in the Roja Mutthiah Research Library in Chennai.

I also spent a lot of time travelling through the regions of Tamil Nadu from which most of the migrants I was writing about came from: Coastal towns like Nagore, Cuddalore, Nagapattinam, Tranquebar.

I travelled in Chettinad to get a better sense of the home environment of the Chettiar community, who played such a major role in the economic development of Southeast Asia.

My research for that book also led me to spend a lot of time in Malaysia, interviewing older members of the Tamil community there about their experiences; and I also visited and did research in Burma/Myanmar.

What are some of the discoveries you made that were a revelation about India and its robust culture of migration to countries along the Bay of Bengal?

In searching for traces of India in Southeast Asia, and traces of Southeast Asia in India, I came to see both regions with fresh eyes. It is hardly a 'discovery', but I was struck forcefully by how vibrant these connections still are.

This was brought home to me when I was travelling through some of the old port towns of Tamil Nadu, and speaking to local people, I realised that almost every single person I met had some family connection with Southeast Asia.

The other thing that struck me is that cultural connections follow their own rhythm.

Even after migration became more carefully regulated -- by visas and passports and permits -- the flow of ideas between India and Southeast Asia remained vibrant.

A lot of the vitality is invisible in the sorts of materials I was primarily trained to work as a historian, which is to say government archives.

Only by spending time talking to people in a Brickfields in Kuala Lumpur, or Serangoon Road in Singapore, or walking around Yangon, did I start to really get a sense of this living history.

Why is History so important?

History shapes us -- our values, our institutions, our politics, our borders.

Understanding History can give us a sense of how the present is only one of several possible outcomes of a complex past, but in doing so, it gives us the hope that positive change can come quickly and unexpectedly.

I'll give just one example from my own work on migration.

In 1870, indentured labour was taken for granted, widely legitimised, seemingly a permanent feature of the world economy -- within thirty years it had come under sustained attack by Indian and Chinese and British journalists and humanitarians; by 1920, it had disappeared, though its legacies have been enduring.

This is not at all what most observers in 1870 would have predicted. But it took work. People organised and protested and came together.

The wonderful historian Mrinalini Sinha has argued that the movement against indenture was in fact the first mass political movement in India.

What are you working on currently?

I am currently writing a book called Unruly Waters, about how water has shaped modern India.

A significant part of the book is a history of the monsoon and monsoon science in modern India; it grew out of my work on the Bay of Bengal.

I hope that this environmental history of water in South Asia will help to illuminate some of the dilemmas currently facing the region as it confronts climate change.

It is also part of my ongoing project to see how we may write histories that cross national boundaries -- which water, of course, does inevitably.

The book will be released in 2019 and will be published in India by Penguin.

How were your growing up school and family years in Singapore?

I grew up in Singapore, where I had all my school education. My parents moved there in 1980 -- my father, now retired, was a banker, my mother is an eye surgeon.

They did not necessarily move to Singapore with the intention of settling there, but by the mid-1980s they realised that they had no wish to move on.

Both of my parents were born in India; my father grew up in Jamshedpur and studied in Mumbai; my mother grew up in Thanjavur and other places in Tamil Nadu; she studied medicine in Thanjavur and then in Delhi.

My younger sister, Megha Amrith, is an anthropologist currently based at the Max Planck Institute in Goettingen, Germany. Her work is also very centrally concerned with migration.

My experience in Singapore shaped my interests in many ways.

Growing up at the crossroads of Southeast Asia, surrounded by currents of Malay, Chinese, Indian, and Western culture, left me with a deep interest in how cultures meet and mix. Singapore remains one of the world's largest ports.

If I have an enduring image of Singapore, it is of staring out from East Coast Park at dusk at the ships' lights on the harbour, with aircraft lights blinking above as they climb out from Changi airport -- that sparked in me many dreams of distant places.

I went to the University of Cambridge for both my undergraduate and graduate degrees, and then taught for nine years at the University of London before I moved to Harvard in 2015.

The two cities I have lived in for longest are Singapore and London, followed by the two Cambridges (England and Massachusetts!)

My wife, Ruth Coffey, is a British barrister specialising in criminal law, and currently also a lecturer at the Harvard Law School. She was formerly advisor to the Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales on criminal law.

We have two children: A son, Theodore, almost 4 years old, and a newborn daughter, Lydia Rupa, born on 5 October this year. Most of my life outside work is spent with the children! I'm a great lover of music, especially jazz.

How often do you visit India? How best do you like spending time here?

India is one of the places I consider home, especially Chennai, which is very close to my heart, and a city of which I have memories built up from childhood.

I visit India as often as I can, several times a year. My trips to India are often a mix of work and seeing family: I visit Chennai and Delhi most often, to use the archives and to meet with many close friends and colleagues in both places.

My extended family, long based in Chennai, have recently moved to Coimbatore.

Travelling in India remains a joy, and there is so much I have yet to see. I have often travelled in India with my wife Ruth, and I look forward to introducing it to my children -- my son Theodore has already been twice, once for my sister's wedding, and once for an extended stay in Chennai and Pondicherry while I was doing research.

In terms of my most beloved landscapes, I must say there is little that can beat the beauty of Kerala for me -- not just in India, but anywhere in the world.