'The obsession of the Pakistan army with India leads to several destabilising things. Support for the Taliban in Afghanistan. Support for groups like the Lashkar-e-Tayiba that have attacked India. Every time you get an attack like that there is a possibility of a war.'

'And then the build up of the their nuclear arsenals. Chances of a nuclear weapon landing in the hands of a terrorist group, or a nuclear war breaking out, are tiny. But they are higher here than anywhere else in the world,' Nisid Hajari tells Vaihayasi Pande Daniel/Rediff.com

When you key in the words 'Partition and India' into the search box of online Indian book sellers you get as many as 2,800 results, and upwards.

When you key in the words 'Partition and India' into the search box of online Indian book sellers you get as many as 2,800 results, and upwards.

That did not deter Nisid Hajari from gambling three years of his life, to go back 70 years and more in time, to extensively research and write his book on Partition.

He was lucky to already have a publisher lined up beforehand. When Houghton Mifflin Harcourt heard of his book proposal, they were immediately interested, which gave Hajari the impetus to explore all avenues of information on this turbulent period.

The Singapore-based journalist with Bloomberg, who was previously with Newsweek International, spoke to Vaihayasi Pande Daniel/Rediff.com

Can you explain the premise of Midnight's Furies?

Everyone asks: Why write another book about Partition? And I will say there have been many. Usually when people talk about a Partition book, they mean the story of the political negotiations that led up to August 15. Or they mean the stories of the trauma and violence that happened in August of 1947. Those are both part of my book.

But the question I had was: Why did a rivalry between India and Pakistan develop, that is still so strong NEARLY 70 years later? That had to do with how the crisis was handled by the leaders, on both sides, or mishandled I should say. So that story, I thought, had not been told yet, in great detail.

The story was relevant to an audience outside the subcontinent now, in a way it hadn't been before historically. The obsession of the Pakistan army with India leads to several destabilising things. Support for the Taliban in Afghanistan. Support for groups like the Lashkar-e-Tayiba, that have attacked India. Every time you get an attack like that there is a possibility of a war.

And then the build up of the their nuclear arsenals. Chances of a nuclear weapon landing in the hands of a terrorist group, or a nuclear war breaking out, are tiny. But they are higher here than anywhere else in the world.

That was the fact that made the story more relevant to Americans, Europeans, to people who weren't directly involved in these events. That was the motivation.

- Part I: 'Nehru was as much to blame as Jinnah for Partition'

- 'They were determined to strangle Pakistan at birth'

But to counter the premise of your book, it could also be that Pakistan is where it is, not just because of the fallout of Partition, but because of its struggle with Islam -- the question of whether it should cling to the South Asian version or link up with the Arabic version. Isn't that at the heart of the problems it is facing today? It is torn within itself?

That is true.

But I don't think that is responsible for Pakistan's support of the Laskhar-e-Tayiba... Or the way the army (reacts).

Pakistan has many issues. But the things that are dangerous for the rest of the world is the behaviour of the Pakistan army and things that they support. That goes back, essentially, to their world view, in which Partition is central. And that has nothing to do with Islam. That is a political issue.

Why do you say that it was Nehru's principles that made Partition unavoidable? Also perhaps when Nehru got to understand Jinnah a little bit better, he got worried that it would be tough to rule a united India along with Jinnah. That might have been a much bigger disaster if they had both bickered, while India was neglected.

It could have been.

It might have been much worse to have a very troublesome Pakistan festering right within the borders of a larger India.

Everyone asks: Wouldn't it have been better if Partition never happened?

The answer is no one knows. It could have been worse. If you could have avoided the hundreds of thousand, if not a million, deaths, that would have been better. But in terms of the stability of India, who knows if it would have been better or not.

Personally do you feel India should have been partitioned? And while researching this book did your view of Partition change?

I actually don't have an answer to that question.

The point wasn't to judge whether it should have happened. Or not. The question, I went into the book with, was just because it happened -- just because two nations were created -- didn't have to mean that there would be this incredible violence.

It didn't have to mean that the two nations would end up hating each other. So the question that motivated me was why did that happen?

The question of whether it should have been partitioned is immaterial to you?

Exactly. There is nothing illegitimate about Pakistan now. It is a real nation.

Do you think the creation of Pakistan was the worst thing for the Muslims of the Indian subcontinent? They have been reduced to a minority in India. The Muslims who migrated to Pakistan were dismissed as muhajirs or refugees/immigrants.

Again it goes back to Pakistan as a fact, now (and the irrelevance of discussing the what ifs). There is no saying what would have happened if you hadn't had Pakistan.

(But today) it is what it is. It has a perfect right to exist, thrive and grow. The situation of Indian Muslims shouldn't have anything to do with Pakistan. That's a situation within India that India should deal with.

But do you agree that the worst affected in 1947 were the Muslims in whose name Partition was wrought and in whose name a new nation was crafted? What do you think were the factors that were responsible for this?

I don't know that I would argue that Muslims broadly would have been better off in a united India. It's counter-factual, of course, and impossible to say for sure -- if Partition had never happened, there's no telling what other pressures might have come to bear on a united India, what other fault-lines might have opened up.

Certainly many millions of Muslims were made destitute refugees by the split, and tens of thousands were killed. They seem to have borne the brunt of the violence in the first couple weeks after Partition. But ultimately, a roughly equal number of Hindus and Sikhs suffered similar fates.

Now, could you say that the Muslims left behind in India, who become an even smaller minority than before, faced bleaker prospects after the split?

Perhaps so. They lost both their political leadership and a good chunk of their numbers. For them, the split made a tough situation that much tougher.

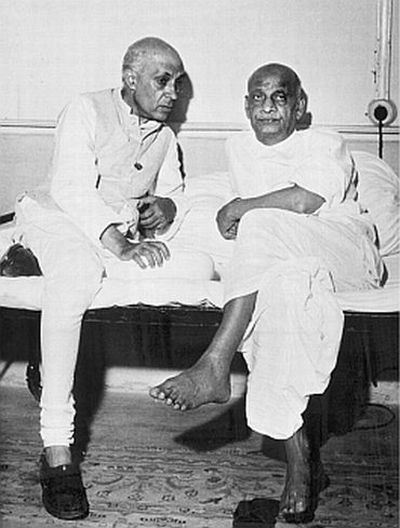

Sardar Patel is not a central figure in your book. What is your assessment of Patel?

He came across to me as a pragmatist. Definitely a hardliner. Definitely more pro-Hindu, I guess you could say, than Nehru was.

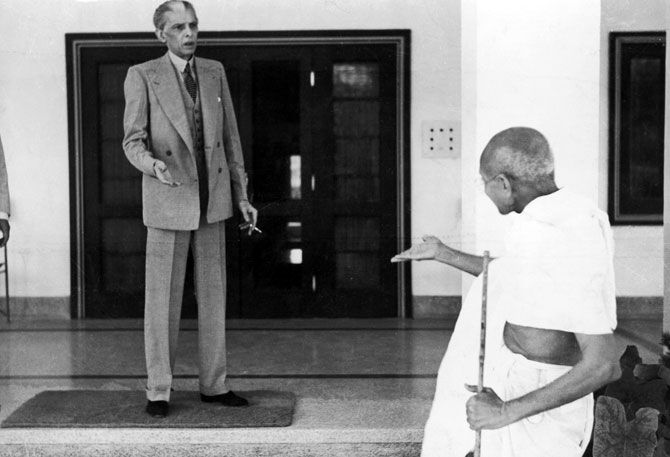

(Maybe) he was someone Jinnah could deal with. It would be interesting to think of what might have happened if it has been Jinnah negotiating with Patel. Rather than Jinnah negotiating with Nehru. They (Patel and Jinnah) never liked each other. But they might have been able to come to a deal -- that they both would accept -- and Jinnah could trust that the other side would live by.

(Like) there is no Jinnah figure in Pakistan (today) -- but having someone like (Narendra) Modi in power, in Delhi, makes it more likely that you could have a deal with Pakistan that would stick. Because the other side could believe that he is carrying the will of the people.

It is like the Nixon-China thing (when US President Richard Nixon went to China in February 1972). You have to persuade the conservatives to make a lasting deal.

You were saying earlier that Gandhi, Jinnah and Nehru had lots of faults. So based on whatever you dug up on Patel, did he seem a little more rational than them?

He was more down to earth and practical than Gandhi and Nehru.

Than all three of them?

No, no, Gandhi and Nehru. Jinnah was very practical.

At the same time Patel was more of a hardliner than Nehru. In those early months after August 15, his attitude towards Indian Muslims was not very charitable. And Nehru had to fight him very hard, in order to defend the rights of the Indian Muslims. That was important.

I don't know what would have happened -- again an interesting thought experiment -- what if Jinnah had lived for 20 years and Nehru had died and Patel had become prime minister.

Would India have been as tolerant of its Muslim majority? Would it have been as secular? Interesting questions. I don't know.

What influence did Maulana Azad's India Wins Freedom and Dominique Lapierre and Larry Collins' Freedom at Midnight have in your telling of the tale of Partition? Or Stanley Wolpert's book Shameful Flight: The Last Year. Why did you feel you had more to say than what they had?

Without naming any names -- because I don't want to single out anyone -- there are good books about Partition. And there are a lot of books that are full of misconceptions and biases.

I based my book primarily on original sources in the archives. If you contrast what people may say in their memoirs, with what the actual document says happened, at that time, you start to see who is a lot more reliable a narrator, than others. So I didn't just take everything at face value.

Maulana Azad's book has some very interesting stuff in it. But there is also some stuff that isn't true.

And Freedom at Midnight, in particular, is based largely on the testimony of (Lord) Mountbatten (India's last viceroy), who is a renowned fabulist. The stories he told, about what happened, got more and more grand, over the years.

By the time they (Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre) were interviewing him, there were many things, that he said, that did not happen that way.

I thought there was still room to do something that was hopefully more accurate.

Azad blamed Patel for Partition. Would you too?

I think there is enough blame to go around for everybody. Nobody comes off terribly well in this.

(Not) the British. Nor the Congress leaders. Nor Jinnah.

When you think about what was at stake, in the lives of these hundreds of million people, everybody could have acted better and more responsibly.

Again, easy for me to say, 70 years later. These were tough decisions to make in the heat of the moment.

How much do the Americans, you have interacted with, know about Partition?

The average American doesn't know anything about this. Most of what Americans know is from the movie Gandhi (laughs). That is the only interaction they would have had with the story... And even Gandhi the movie is pretty inaccurate, in a lot of ways.

What about the British role in Partition?

The British are to blame for a lot of mistakes that led up to Partition. In the years before Partition. If the British had promised independence to India, at the beginning of World War II, as they were being pressured very heavily to do by the United States, there wouldn't have been a Partition.

Jinnah's position was not so strong at that point and it (Partition) wasn't a widespread demand. India or the Indian population would have joined the war effort, in a way that it didn't.

Churchill fought too long to devolve power. You can go way back to separate electorates and all that stuff.

But in terms of the time period I am looking at it was not the British's intention to partition India.

They wanted to leave India united with a strong central government that was an ally of Britain preferably in the Commonwealth. That was in Mountbatten's instructions from London. This was the goal.

This idea that the British were somehow trying to weaken India just makes no sense to me at all.

But perhaps a certain amount of disinterest towards the end was also to blame? As Britain wound up its rule in India it was also involved with the aftermath of World War II?

But perhaps a certain amount of disinterest towards the end was also to blame? As Britain wound up its rule in India it was also involved with the aftermath of World War II?

The British were focused on it. They needed to leave. They couldn't stay forever.

The speed with which they left, obviously left Pakistan weaker than it otherwise would have been. That wasn't the original intentions of the British.

As I write in the book, they had some vague plan that they would continue overseeing Pakistan till its government was set up. They clearly had not thought through the logistics of it.

The disinterest problem was more at the ground level where you had officials in the Punjab who had less incentive to stem the violence, because they were going home to retire, things like that.

How did you balance any biases you might have had?

Obviously, it was easier for me (to do that) than an Indian or Pakistani. I am an Indian American, but I grew up, my whole life, in the US. And I didn't come to this with any particular issue. I think it was easier for me to take a couple of steps back and judge the biases on either side.

I wanted to be very careful. I was very self conscious, all the way through, of trying...

To not villainise Jinnah?

Not villainise Jinnah, especially.

That was an easy one to start with. Clearly, in a tragedy of this scale, the idea that one person, or any one side, could be predominantly to blame seems crazy to me. Obviously it had to be a combination of factors... I wanted to be extra careful about that...

Because the material available for researching that period -- be they documents or books -- needed to checked for that?

The material is full of biases. But if you read all the material, across the range, you can kind of place it on a spectrum, and then you can sort of take the parts that seem least biased, or most unbiased.

Also it is very important to crosscheck, or try to analyse and see, how different people view an incident and try and figure out what really happened.

There were people who were more disinterested than others. US diplomats were a great source -- State Department archives -- because everybody would talk to them, Jinnah, Nehru, because they had nothing at stake here. Their reports were fairly clean and fairly unbiased.

American journalists were less -- I don't know if bias is the right word -- but compared to the British, they had fewer hang ups about India.

Why, in your view, is re-examining Partition so important? A new, post-Partition generation is on the rise in both nations. Perhaps with them we will hopefully see the ghosts of Partition finally interred. In that sense, recalling the events of pre 1947, who did what could that reopen old wounds, bring back forgotten memories? Shouldn't we lay the subject to rest?

A vast majority on both sides were born after Partition. They have no direct experience of it.

But if you do polls, two-thirds of the people, on either side, view the other side with suspicion. You can't blame all that on Partition. But definitely that attitude is there.

If you just ignore what happened, and allow everyone to think what they think, about it, you have two narratives that are -- not diametrically opposed -- but are in conflict.

How can you move forward? How can you really trust the other side, if you really think x-y-z happened in the past. How can you break out of that mindset...

In the US, obviously, people are very interested in history -- Civil War, World War II -- but there is a very American attitude to history, which is, it is in the past. It is history. Let's move on. That is because they examine it, examine it threadbare. Then you can move on.

For a general audience, I think, it is important to face up to the past.

And remedy all the schoolbooks?!

Exactly. That's a big thing... But that's it. You need to have it clear, as unbiased as possible. Then I think both sides will see there was a lot of blame to go around. These were a lot of human mistakes people were making. Sort of understandable, why they did it. Jinnah didn't intend for a million people to die...