'Nehru's inability to take religion seriously as a category led to serious errors of judgement in his dealings with the Muslim League, and later, also with the Hindu right.'

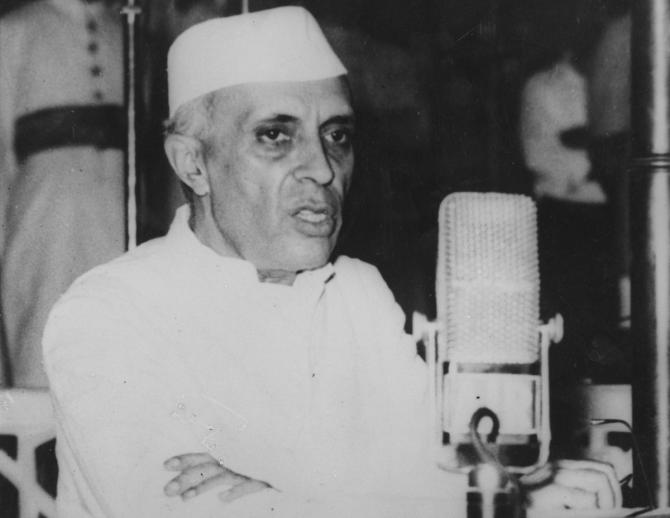

Contemporary political discourse in India is never complete without a heated debate on Jawaharlal Nehru; a debate on what he did and what he didn't.

How often do you come across statements from both sides of the political aisle, either crediting his vision for a recent achievement or blaming 'his lack of foresight' for an existing conundrum, especially Kashmir and China?

However, this discourse has also invigorated interest in wanting to know more about Nehru and his views and policies and their impact on current times.

A new book by authors Tripurdaman Singh and Adeel Hussain is an attempt in this direction.

Nehru: The Debates that Defined India offers a way to understand India's first prime minister through the debates that he had with four stalwarts of his time: Muhammad Iqbal, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, Vallabhbhai Patel and Syama Prasad Mookerjee.

The debates cover several issues that are very much relevant even today, like communalism and India's relationship with China.

"Whether it is the question of religious orthodoxy, political representation for Muslims, India's foreign policy and its place in the world, or civil liberties and free speech -- these debates are far from settled," Tripurdaman Singh and Adeel Hussain tell Rediff.com's Utkarsh Mishra in Part 1 of an eloquent interview.

The book is indeed a novel approach towards the study of Nehru's legacy. What was your idea behind selecting these four particular debates?

Tripurdaman Singh: As we mention in the introduction, Nehru remains central to modern India and the shape that it has taken -- his ideas continue to constitute centre ground in Indian politics.

But before they achieved the status of received wisdom, they were vigorously contested.

In that sense, it was natural for us to focus on the period before Pax-Nehruana, before Nehru came to wield unchallenged executive power. This provided a natural bookending on either side.

These four debates were the most important, the most consequential. They were foundational in nature -- they defined the contours of modern India.

Concurrently, we also wanted to speak to the present moment, and these four debates remain deeply relevant to contemporary politics.

Whether it is the question of religious orthodoxy, political representation for Muslims, India's foreign policy and its place in the world, or civil liberties and free speech -- these debates are far from settled.

The ghosts of the original protagonists loom large over current-day discourse. For us, the debates really selected themselves.

Adeel Hussain: We were informed by debates that are still ongoing today.

India's foreign policy toward China; the Hindu-Muslim conflict; separatist movements; and the executive hollowing out the Constitution by asserting pressure on the courts are concerns India is facing right now.

We wanted to provide a historical background that would allow readers to compare the answers given by political leaders in the contemporary context with the dominant political leaders that Nehru faced.

Nehru's debate with Allama Iqbal on Islam happens in 1935, around the same time he also wrote his autobiography, and his dialogue with Jinnah on the question of minorities happens in 1938.

In all these debates and conversations, and even in his autobiography, Nehru takes the view that religious conservatism is a thing of the past and scientific advance and modern civilisation will soon over-run it.

However, in the years just before Partition and after witnessing the bloodbath during it, did he change his views about communalism and how it can drive a whole population to commit such atrocities against other human beings simply because they worship a different God?

Tripurdaman Singh: His views shifted, but there didn't seem to be a fundamental change.

He continued to see religion as a regressive force, out of sync with the modern world, to be eclipsed by modernity. It was not a category worth taking seriously.

For him there was a primary problem, poverty; and there was a primary solution, socialism.

In this scheme of things, religion was either a front for elite interest, or a form of false consciousness that would be cured by modernity.

This fundamental position didn't change, although Partition did bring home the explosive potential inherent in religious strife, which in turn caused Nehru to become a lot more sympathetic to Muslim concerns.

Adeel Hussain: Rather than change his historicism -- the idea that history had an explicit purpose and an aim toward which it was moving -- Nehru felt encouraged by signs of what he considered regressive behaviour during communal violence in the 1930s and 1950s.

For Nehru, it showed how backward Indians were and how desperately they needed a leader who would rid them of what he considered superstitious beliefs and nudge them towards scientific progressivism.

Do these debates show that Nehru's understanding of communalism was naïve? Although in his autobiography, he says that majority communalism is much more dangerous than minority communalism. Today, we see majoritarianism at play not only in the subcontinent, but also in some Western democracies too.

Tripurdaman Singh: I wouldn't say naïve, I'd say he profoundly misunderstood how important religion was in the lives of the people.

He also consistently failed to appreciate that it was also a political category and an axis -- a very easy axis -- of political mobilisation.

Communalism was more than just elite machination or the false consciousness of the ignorant masses.

Nehru's inability to take religion seriously as a category led to serious errors of judgement in his dealings with the Muslim League, and later, also with the Hindu right.

Adeel Hussain: Nehru's view on communalism was not naïve, but he certainly misread how important religion was for political mobilisation in South Asia.

The more communal violence ensued, the more Nehru felt he had to push for a harder line that solely focused on material uplift without any appeal to religious identity.

This reasoning may have led Nehru to withdraw from the Cabinet Mission Plan, a power-sharing agreement with the Muslim League that would have avoided Partition, and which directly led to one of the most significant violent events: The 1946 Calcutta killings.

Once the League left the negotiating table and called for hartal, it was too late for Nehru to make amends.

Many criticise Nehru for not bringing a legislation to reform Muslim personal law while he pushed the Hindu Code Bill despite massive opposition.

Apparently because he didn't want minorities to feel threatened in a country that had just undergone a bloody Partition.

Does it signify a change in his attitude from a decade ago when he seemed to be dismissive of the concerns of minorities that Jinnah tried to outline in his letters?

Tripurdaman Singh: It does. While Partition didn't change Nehru's attitudes towards religion per se, it did make him much more sympathetic towards Muslim religious and cultural rights.

He was anyway, as my old supervisor Chris Bayly used to say, a 'liberal communitarian' in that he was not particularly invested in individual freedom.

After Partition, he wanted to prove that Muslims could live peacefully in a 'secular' India and thus undermine the two-nation theory. This demanded that Jinnah's contention that a Hindu majority would dominate, or bully, a Muslim minority was demonstrated to be false.

After Partition, he wanted to prove that Muslims could live peacefully in a 'secular' India and thus undermine the two-nation theory. This demanded that Jinnah's contention that a Hindu majority would dominate, or bully, a Muslim minority was demonstrated to be false.

Nehruvian secularism -- protected religious and cultural rights for minorities -- was also closely linked to his internationalism and his role as a global statesman fighting against imperialism and capitalism, which depended on India's image as a progressive, secular democracy.

Adeel Hussain: Yes, I agree. There was a clear change in Nehru towards appeals from Muslims regarding the protection of their religious rights before and after Independence.

Nehru's first aim was to dismantle colonialism which he saw as the most exploitative offspring of capitalism. According to Nehru, this was only possible when the people of India united behind a singular message that was not guided by religion.

A dispute over the role of religion in political mobilisation was at the heart of the rift between Nehru and Jinnah.

After Independence, Nehru wanted to dismantle one of Jinnah's major concerns that had led to Partition: That national majorities in democracies always dominate and bully minorities.

For this reason, Nehru allowed the continuation of Muslim personal laws without altering them while pushing to reform Hindu laws and bring them in accord with practices in Western countries.