'It struck me as horribly unjust that we all stood up for Nirbhaya, but we had all forgotten Bhanwari Devi.'

'Our lives were saved by a group of soldiers who we did not know. The Tiger Hill assault had started and I had a sat phone and was trying to call my office. I didn't realise I was standing next to an ammunition dump...'

'I like to see myself as a troll-slayer and I have realised the best way to do that is to ignore them. Nothing bothers them more.'

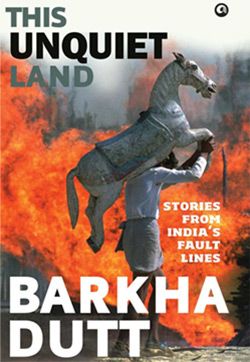

Television journalist Barkha Dutt discusses her first book The Unquiet Land with Rashme Sehgal.

One of India's foremost television journalists, Barkha Dutt, in her first book The Unquiet Land, notes her experiences while covering major events in the country from the Bhanwari Devi rape case to the Kargil war and the Gujarat riots.

She believes the fault lines in India run wide and deep, whether they be in the area of politics or cultural practices -- and we have to address these before we can move forward as a nation. She spoke to Rashme Sehgal for Rediff.com

Your book looks at the broader picture about developments in the country and then very successfully pegs them to an individual story which helps to bring the point alive. You start with the case of Bhanwari Devi, the sathin who was gang-raped near Jaipur. Bhanwari Devi was a case that was covered extensively by the media. I too was one of the journalists who wrote extensively on Bhanwari Devi.

That is the irony. We have all written on Bhanwari Devi, yet 20 years later, nothing has happened with her.

Bhanwari Devi was like a test case?

That is the irony. It is because of Bhanwari Devi that we got the Vishakha guidelines on sexual harassment. So all the sexual harassment guidelines that much more privileged women are able to benefit from and seek protection from, the woman we owe it to, two decades later is still fighting for justice. And nobody talks about her.

She is not on the national headlines anymore. She has been forgotten. It makes me feel terrible. It makes me feel quite ashamed as a journalist. I keep feeling I should revisit the story which is why it is so important for me to include it in the book.

What struck all of us about Bhanwari Devi was her dignity...

Yes. Such enormous dignity and such quiet strength.

You juxtapose this with the Nirbhaya case. The Nirbhaya case received so much media attention especially since it had been so poorly mishandled by then chief minister Sheila Dixit. How did you respond to the Nirbhaya case?

You know what I felt -- I was seeing it both as a journalist and as a woman - is that the gender discourse has shifted in the country after Nirbhaya. For those of us who covered gender, you know that it was never front page. It was never a lead story on television news.

The one thing that has changed after Nirbhaya is that gender is now finally a hard news issue.

For those of us who cared about this issue, we had to fight to give it the space it deserved. That is the good part. But I was struck by the irony that one of the first stories I covered as a young reporter was on Bhanwari Devi.

I could see my entire journalistic life in the journey from Bhanwari Devi to Nirbhaya. It just struck me as horribly unjust that we all stood up for Nirbhyaya, but we had all forgotten Bhanwari Devi.

I hope that after all this she too will one day get what is her due.

From the subject of women, you then move on the Kargil war and how this turned out to be an extremely difficult and dangerous assignment for you.

From the subject of women, you then move on the Kargil war and how this turned out to be an extremely difficult and dangerous assignment for you.

The Kargil war was my classroom. Where I learnt so much. It was one of the biggest stories I covered in the early part of my career. I did not have too much experience, just a couple of years of experience.

In terms of the danger, tab technology bhi nahi thi, there was no live uplinking, no OB vans, no mobile phones. Just getting our story back to Delhi, just getting information back, we used to run after the chopper pilots who were carrying dead bodies and say will you please carry our tapes.

Communication was a huge problem. I had never seen violence and war before. I did not wear a bullet-proof vest in Kargil; we were so unprepared for war.

The army did not ask you to wear a bullet-proof vest?

No. The army was very hesitant to allow us near the battle front. They said, 'We are fighting a war, we cannot look after you all.' We were given permission on the promise that we would look after ourselves.

So we were three, four younger reporters, we would get into a car, raat ko nikal jate the, sleep in the car, we would sleep behind a boulder, there were no bathrooms, there was no food and sometimes there were briefings, we would get information but other than that we were on our own.

It was really the biggest and most intense learning experience of my life.

I also covered the Kargil war, but a lot of my reporting was from around and from the peripheries. Were you stationed in Kargil?

We were first based in Kargil. We used to drive to Drass where the Tiger Hill assault was happening. Because it was on the main highway, we could get access to stories. We were on the stretch between Drass and Kargil all the time, not in the peripheries.

We were obviously not in the upper reaches where the assault was happening and, of course, we could not go there.

It must have been very tough to have been on your own.

Our lives were saved by a group of soldiers who we did not know. The Tiger Hill assault had started and I had a sat phone and was trying to call my office. I didn't realise I was standing next to an ammunition dump.

Shelling had started from Pakistan when a soldier came up to me, 'Ma'am, what are you doing?' I said, 'I am making a phone call.' He said, 'No. No. If a shell falls on this ammunition dump we will all die.'

He said we have to move from there and he pulled me to an underground bunker. I told him I could not find my cameraman. He said he had also lost his partner and he would go and find them. He found my cameraman, he found his own guy also. That night, that phase for 24 hours, we stayed in the underground bunker. But other than that we were on our own.

It didn't seem proper at that time to impose on the army at a time of war.

That is interesting to learn because I remember attending a seminar in which some activists criticised you for receiving five star treatment from the army.

All kinds of bakwaas has been said. I would challenge them to give me any kind of evidence for this.

Apart from that one night in the bunker, I remember my nights in a rundown hotel in Kargil, nights spent in a car.

I lost my bags because I was separated from one team that was left behind in Kargil. I was living in two shirts and one pair of jeans for ten days during the first time and then I then went back to Kargil a second time over.

One gets used to this rubbish being said about me.

There was also the rumour about you using an iridium phone which gave away Indian army locations to the enemy. You mention this in your book.

I talk about this in the context of it being so ridiculous. When I came back from Kargil, I mentioned this in my book, how the then army Chief General (Ved Prakash) Malik had called me for a cup of tea.

He congratulated me over the coverage which he said was really great and how it had helped to keep the sentiment of India strong for the army. And then I said, 'Sir, I have a question for you. Some people had spread the rumour that the iridium phones, without realising, compromised the safety of the Indian forces.' 'Rubbish!' he said, 'the army was using 60 of the same iridium phones.'

He writes about this in his own book on Kargil also. I find this charge so ridiculous. Even if you tell people that this is what the army chief has written in his own book, they will not accept it.

This obviously comes from a place of malice.

Your book then moves on to describe the Gujarat riots and how that was also a difficult time for you.

The Gujarat riots were a very difficult time for me. I talk about the 1984 anti-Sikh riots and how if 1984 had happened on TV, it would have played out very differently for the Congress.

I think they got away rather lightly because this was not a riot that was covered on television. But I also use it to talk about the larger debate on secularism which has become completely polarised today.

How have we reached a point where secularism has become a bad word. I feel I hit out as much at the Congress as I do at the BJP. The Congress has also subverted the integrity of the word secularism which I write about in my book.

Under the Congress, we have seen some of the worst riots which have happened in our history. You cannot blame the BJP alone. Both political parties have made this a suspect word which it should not have been. It should have been a given principle of India.

But yes, covering the riots was extremely difficult. Yes, it was the first time I had covered a riot. I did not know the rules of the game.

It was the first time I had covered a war, the first time I had covered a riot. By then we had live television, but we had to be very careful that something we said or showed on TV did not inflame the situation further. All these have been tremendous learning experiences.

From the Gujarat riots, your book moves on to 26/11 and the terrorist attack on Mumbai which then raised the whole issue of reporting live given that handlers present were monitoring the attack.

My view on 26/11 is that before that we had covered anti-terror operations but we had not seen a situation where the handlers of an attack were watching it on television.

We did, for example on Kashmir, show encounters and operations live, when we could, when we had access to them. It did not compromise the operation in any way. For example if the army or paramilitary forces were blowing up a house where terrorists were hiding, which has been often caught on camera happening in real time, but obviously from a distance. You are not right in there.

Our Kashmir reporters -- sometimes me myself -- have stood behind the security cordon where you were allowed to stand and have covered these operations from there.

It had no effect on the operation because there were no handlers. These were localised conflicts between terrorists/militants and security forces.

In Mumbai it was different. Nobody in the media knew that these handlers in Pakistan were monitoring the operations from our news. NDTV took a decision 36 hours after the attack to do a 15-minute deferred live telecast.

It was a learning experience for the entire industry. One of the codes we now have amongst all channels is never to show an operation live.

But what stopped the government from making one phone call to editors of ten channels to stop this live telecast? If they had called us and told us do not show it live, we would have stopped.

The government did not know about the handlers.

That's what I wonder now. If they had called us and said don't show it live, we would have stopped it. It was an inadvertent error by the entire industry. We had no idea, but nor did anyone tell us. There was a complete breakdown of communication. It has been a learning and now nothing is shown live.

Would you agree that the BJP is savvier in its communication strategy than the Congress?

No question that the BJP is smarter in communication and much savvier. But I do feel it would benefit this government to communicate more. Sometimes they communicate too late. Take the example of the Dadri lynching, it would have helped them if they had communicated earlier.

The BJP changed the rules of the game in the 2014 election, it was a masterful communication strategy, but in government while they understand the media moment, they should communicate more and quicker. The Congress is still playing catch up.

What made you write this book especially since you remain such an eager participant in the present discourse taking place in the country?

I decided to write the book because I felt I had experienced a gamut of events from politics to war and I should write about it before my memories dimmed. I also felt I could use the experience to make a larger argument about some of the most contemporary issues that confront India.

Also, writing allows you a certain kind of deep diving and context that television does not.

You mentioned in your book that you were part of the anti-Mandal agitation that took place in 1992. What was your learning curve from it?

As I write in the book, I took part in the anti-Mandal agitation mostly because I was charmed by the idea that there was something to march against. It made one feel rebellious. I think my understanding of caste dynamics while in college was next to nothing.

This does not mean that I don't believe that caste quotas are not politicised -- but the fact is that at that time, I was rather ignorant about the multiple dimensions of this issue.

The Dadri lynching and the Muzzafarnagar riots seem to flow out of the Gujarat riots only because the Manmohan Singh tenure seems to have remained relatively riot-free. Of course Muzzafarnagar ostensibly took place during Dr Singh's prime ministership but it seemed to have been triggered by the BJP. What do you feel?

No, I disagree with that. I would say that for both the Dadri lynching and the Muzzafarnagar riots, the accountability lies both with the local BJP and the Samajwadi Party.

In fact a judicial report on the Muzaffarnagar riots that has partially leaked says as much. And let's not forget that 1984 and 1992 before that happened on the Congress watch.

Your book mentions how post-Gujarat, Narendra Modi met journalists several times in Arun Jaitley's house, but neither you nor Rajdeep Sardesai were invited to these meetings. Why do you feel that happened?

It wouldn't be for me to speculate on the reasons! But generally speaking, I do have the impression that the PM has held onto the feeling that he was not treated fairly by the English media in reporting the 2002 Gujarat riots and, of course, Rajdeep and I were among those who reported the riots for TV.

Does the present regime continue to hold a 'grudge' against NDTV and you more specifically?

No, I don't see any grudge... I would say that many people in government are politicians I have known for years as a journalist and I have a perfectly comfortable professional equation with most of them.

How have you seen television change in the last two decades? Do you feel it is getting increasingly more polarised and Americanised and how does that fan out for younger journalists?

I have seen television move into a primarily talking-heads driven production instead of the telling of stories. Also yes, I do believe that there is an increasing shrillness on television because it reflects the larger political and ideological polarisation that India is going through -- much like the US where you are either Republican or Democrat, and even the channels can be identified as such.

Here we have not yet reached the point where channels wear political affiliations on their sleeves, but there is increasing pressure from social media especially to take sides.

Someone like me, who sees myself in NO CAMP wonders what will happen in the future to those of us who are not defined by ideological dogma. And will this trend be the death of nuance?

You have described the Radia tapes as having been one of the most hurtful experiences in your journalistic career. Why was that and was being cross-questioned by fellow journalists a kind of redeeming experience that you allowed yourself to undergo?

I say most hurtful because it was the first time in my life that my integrity was questioned and I was both angry and hurt by that. Nevertheless I was keen on being questioned by a panel of peers and editors and allow viewers to see this unedited, with not a word removed, to make the point that just like I ask people questions, I should be prepared to answer them as well. And I did.

Having covered the Kargil war followed by the Vajpayee-Musharraf dialogue, what do you feel went wrong with the peace initiative?

For us in India, the central issue has always remained terrorism. It is terrorism that is the obstacle to the peace process. My own take is Kashmir could be solved if both countries could resolve the rest. But I think it's quite clear as I say in my book that India and Pakistan will perhaps remain like this for the foreseeable future.

Every government has been compelled to keep trying to talk. Perhaps even just the inching along helps at least manage the relationship in phases.

You broke the story regarding the secret Modi-Nawaz Sharif meeting in Nepal. Do you see any commitment on the part of the Modi government to resolve the contentious issues facing both countries?

To me the story I broke about the covert, under-the-radar meeting between the two PMS during the SAARC summit in Nepal last year really reflects a keenness in both to move ahead despite different sorts of domestic pressures in both countries.

I am told the book excerpts have caused a huge furore in Pakistan. I don't follow why a secret meeting away from the media gaze and the protocol and pressure of formal meetings should be treated like a scandal, specially when meaningful work gets done only in the back channel.

Yes, you could have questions about why (businessman) Sajjan Jindal was an informal conduit. My impression of that too is that it indicates that the two PMs have decided to keep the reins of the relationship in their own hands and have used him (Jindal) as an informal message mechanism when necessary.

I have seen the denials, of course, by all sides, but as I wrote in the book, it was, of course, a perfectly deniable chat that the two PMs had. And I don't think that's wrong. I think it is necessary in diplomacy

Your book cites many examples of people you have encountered who have been brutalised and then forgotten by the government. How do you react at a personal level to these meetings and what does this tell us about our own country?

It's disturbing, of course, but then we in the media and I include myself are just as guilty for living headline to headline and having a short attention span to see things through.

How do you react to rumours that you are married? What is the truth?

It is rubbish and an example of slanderous sexism. People say -- and Wikipedia even has an entry for it -- that I am married to a Kashmiri Muslim to explain my political views. Can you believe that!

I used to initially tell them the rumour was rubbish, but then when I keep getting asked the same question again and again -- I have now just learnt to laugh it off.

What do you feel about the growth of social media and the fact that you are often trolled? Sometimes this can get very malicious. Is this because you are a woman?

I definitely feel women get trolled in a very different way from men on social media. We see it not just with me, but so many of my female colleagues. Even rape threats are not unusual.

But the flip side is that there are some great conversations online as well and some great minds and new commentators and the instant volley of feedback is exciting and informative.

I like to see myself as a troll-slayer and I have realised the best way to do that is to ignore them. Nothing bothers them more.

English television has thrown up three wellknown anchors: Rajdeep Sardesai, Arnab Goswami and you. All three of you follow different kinds of anchoring. How would you describe your style?

I guess I would say I am conversational and informal and find that sometimes the hint of a smile accompanying the tough question can elicit the headline you were looking for much more than badgering the interviewee. But to each her own!

Tell me about your relationship with the Roys (NDTV founders Prannoy and Radhika Roy). What made you decide to branch out and distance yourself from NDTV?

The Roys have been mentors and guides to me. This was my first job. They have known me since I was a young 20 something! They have given me endless opportunities to learn and discover myself and have always enabled my growth.

I am grateful to them for all that I have learnt and much of this book would not have been possible without NDTV and the experiences it has allowed me.

I have not distanced myself from them or NDTV at all. I continue to do just as much TV with NDTV as earlier. The only change is in my contract which now by virtue of a consultancy allows me to pursue non TV ventures on my own.

Otherwise, I remain just as connected to NDTV as ever and am proud to be so.

© 2025

© 2025