'Everyone was talking about migrants, frontline workers and cops...'

'Nobody was talking about sex workers during the pandemic.'

On December 5, 2021, a documentary on the plight of sex workers in Kamathipura (a 'red-light' area in Mumbai) during the pandemic was screened at the city's National Centre for Performing Arts.

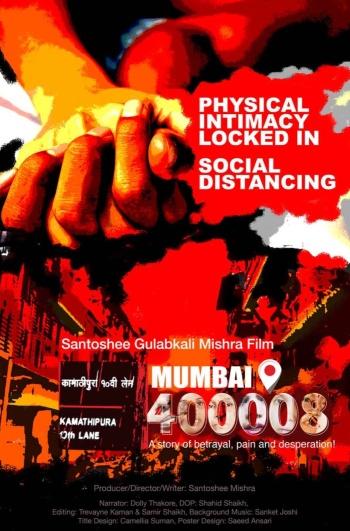

Mumbai 400008 -- which is the pin code for that area -- was made by journalist Santoshee Mishra.

"They are trapped in a vicious circle that needs to be showcased to the world," Mishra tells Rediff.com's A Ganesh Nadar.

Why did you make this film?

I have been a journalist for 21 years. My pleasure is in writing.

On this topic, there is a lot of colour and intricacies involved.

I have written a couple of stories at the beginning of the pandemic.

I wanted others to see what I saw. They are an invisible section of society.

I have never made a film before this. I decided to make a documentary.

It represents our country. Here prostitution is legal, but soliciting is illegal. In developed countries, it is allowed.

I wanted to show their suffering.

Why call it Mumbai 400008?

Being a journalist you first think of a headline.

It is Asia's biggest 'red-light' area. Pin code is a landmark.

The name Kamathipura comes from workers who came from Andhra Pradesh. So I chose Mumbai 400008.

The number of sex workers in Kamathipura is currently about 10% of what it was. Do you know the reason for this?

The numbers of sex workers are directly proportional to poverty.

Trafficking from Nepal and Bangladesh has been reduced. Now they are coming from within the country.

The cost of living in that area is very high. They have shifted to outer areas of the city.

Kamathipura is a well-known place. Outsiders know about this area and come here. Here a clientele still exists.

7,000 sex workers are registered with NGOs. Most of the NGOs are supporting the sex workers, but some of them don't approach the NGOs.

Other industries are also there in Kamathipura. Normal families are also there.

There are still some commercial sex workers who sit in bungalows; they don't come on the road.

How much money was spent on this film? How did you finance it?

It was a good amount. I spent my own money.

We used four cameras, then edited and work in the studio, all that was expensive.

Dolly Thakore, who did the narration, did not charge anything. I had to spend on the music too.

NCPA did not charge for screening. The curator at the NCPA Mukesh Parpiani told me to just bring the film and that I did not have to pay a single rupee.

The film is 35 minutes long; it has been edited very well. How many hours did you shoot?

The shooting took six months.

Some of the women we spoke to were emotionally upset and so we had to stop shooting and go back another day.

We worked for 50 hours in the studio to edit. It took a year to complete the film.

You have not made any attempt to shield the identity of the sex workers.

Nowhere do they say that they are sex workers. It is a problem of society.

I wanted to show the real picture. There are no vulgar or sleazy shots. They gave legal consent to be filmed.

Was it very difficult to convince them to speak on camera?

Yes! Initially, it was difficult, that is why it took 6 months.

NGOs were giving food packets and others were giving rations. I have worked there as a journalist.

Everyone was talking about migrants, frontline workers and cops, nothing wrong with that.

Nobody was talking about sex workers during the pandemic, so I wanted to write about it.

People who gave them dry rations did not realise that they did not have money to buy gas cylinders or kerosene.

They get loans easily as they pay daily interest. They are trapped in a vicious circle that needs to be showcased to the world.

Was it dangerous shooting in Kamathipura?

Once when we were shooting at 3 am, cops threatened us, asking us why we were shooting at that time, even though we had permission.

Pimps did not like us talking to the girls. I had to convince them that it was good for the girls.

Sometimes we recorded on our mobile phones as we could not take the big cameras.

I know the people in that area for many years and so I could do it.

It is a documentary and it is not meant to make money.

You have included a scene from Pakeezah. What was the reason?

This is an invisible section of society. What Pakeezah showed was that a woman can come out of this life and be respected.

As there are clients, so there are sex workers. We took permission from Kamal Amrohi's son, he gave it gladly.

Do you feel you have achieved what you set out to do when you saw the completed film?

Yes! The script is mine. People have accepted that they exist. I have shown a problem.

It is up to the viewer to accept them, to acknowledge that they are there.

People at the NCPA screening said that it was impactful.

Is it true that NGOs are doing more for the sex workers than the government?

There are no schemes for sex workers. There is a scheme for Devadasis and for abandoned women.

NGOs are trying to fill the gap. They are babysitting for them, telling them about safe sex, helping with their children's education.

The NGO is doing what the government should have done. They are not a vote bank.

What future do the sex workers face?

They are in debt. Their clientele are labourers. Business is down.

Their earnings are less. But now some business is happening.

What is the message you want to give with your film?

The message is that we should identify the problem and then try to solve it.

People don't admit that they are a part of society.

I hope my daughter when she grows up accepts them as part of our society.

What is the topic of your next documentary?

I have written another script. I will tell you after I finish it.

Feature Presentation: Rajesh Alva/Rediff.com

© 2025

© 2025