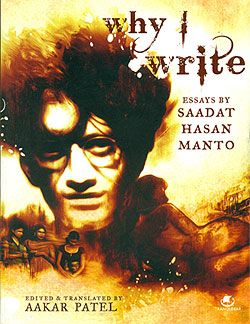

'Manto is the only writer to grasp what the project of Pakistan would eventually mean,' says Aakar Patel, who has translated a collection of Saadat Hasan Manto's essays in a just-released book Why I Write.

'Manto is the only writer to grasp what the project of Pakistan would eventually mean,' says Aakar Patel, who has translated a collection of Saadat Hasan Manto's essays in a just-released book Why I Write.

One writer who took the Urdu language to its zenith is Saadat Hasan Manto. A brilliant story-teller, he wrote some of the greatest short stories in Urdu, especially about the Partition of India.

Considered one of the subcontinent's finest writers, Manto reluctantly left India for Pakistan, complaining against Jinnah's stupidity and fearing for the safety of his three daughters.

He died at 42, leaving behind a magical repertoire of writings.

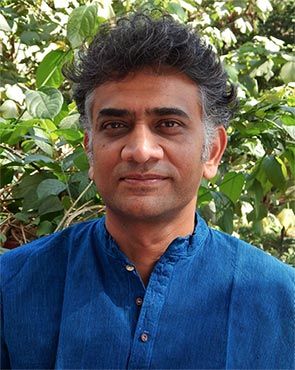

'It is difficult to think of better literature in our language than his. His stories represent for many the high watermark of Hindustani writing,' writes author-journalist Aakar Patel, below, left, who has translated some of Manto's non-fiction into English in his new book, Why I Write.

Most of the stories in the book, except two, to Patel's knowledge, have not been translated before. The stories remain relevant even today because they are a sharp dissection of what ails the subcontinent six decades later.

Patel, who began learning Urdu in 2000, has edited newspapers in English and Gujarati for the Dainik Bhaskar group and the Mid Day group, where he also oversaw the Urdu daily Inquilab.

He is a columnist for the Mint Lounge and the Pakistani daily, Express Tribune.

In an e-mail interview to Syed Firdaus Ashraf/Rediff.com, Aakar Patel speaks about Manto's move to Pakistan after Partition, the future of the Urdu language and why he chose Manto's short stories as a subject for his book.

Do you think Manto's stories are relevant today?

His predictions of Pakistan and the trajectory of the Islamic State are shockingly accurate and prescient. I say shockingly because Manto is the only writer to have absolutely grasped what the project of Pakistan would eventually mean.

Everything that we read about in today's papers he had prophesied.

Is it true that Manto left India because anonymous letters were sent to the Bombay Talkies studio that Muslims must not be employed or else they will burn the studio?

I think he left because he feared for the safety of his daughters. They were very young (in fact so was he) and I am quite certain that pressure from family and from his wife would have influenced him.

Do you think Manto left India because he did not see a future for Urdu in India vis a vis Hindi?

Not at all. In fact, in one of the essays I translated, he writes about how irrelevant this divide is.

Can you throw some light on Manto's personal life? What did his wife and three daughters feel about migrating to Pakistan?

Can you throw some light on Manto's personal life? What did his wife and three daughters feel about migrating to Pakistan?

He was of Kashmiri origin, but the family lived in Amritsar. His father died early and the family did not have much money. Manto was a poor student and dropped out of Aligarh Muslim University (after failing, of all subjects, in Urdu!).

He came to Bombay in the 1930s and got a job as a journalist. He also took up part time employment in studios as a film writer. He was not a good writer of scripts and does not have any major hits to his name.

He came to Bombay in the 1930s and got a job as a journalist. He also took up part time employment in studios as a film writer. He was not a good writer of scripts and does not have any major hits to his name.

He was, however, exceptional at writing short fiction, particularly about the urban experience. I think he 'gets' Bombay better than any writer before or after him, including the man I consider second best, Behram 'Busybee' Contractor.

This talent of Manto drew famous people, like Ashok Kumar, to him and he was able to call them his friends. He left when Bombay turned tense and violent during Partition.

One of his daughters, Nighat, was born in Pakistan, so they were all too young. My speculation is that his wife would have been concerned about the family's safety, and her brother lived in Karachi. That might have influenced them to move.

Who were his close Hindu friends and why did they not stop Manto from migrating to Pakistan?

I don't think at that time people realised that the divide would be this permanent. It is said even Jinnah held on to the idea that he would spend his vacations in Bombay after Partition!

The Mantos lived in South Mumbai, and he describes in one piece the tensions in Mahim and in Bhendi Bazaar. This is powerful stuff and on reading it I realised that it would have been difficult for any family that had the option in those years of moving, to not move to safety at least for the short term.

Was Manto a complete misfit in Pakistan?

Was Manto a complete misfit in Pakistan?

Absolutely and totally. He was liberal by instinct and he loved the free atmosphere and mixed population of Bombay. It was his real home, and it produced the writer in him.

Entertainment can only be produced on the cusp of obscenity and only Bombay was liberal enough then and now, to be home to the Subcontinent's entertainment industry.

Manto was tried by British courts for obscenity, but finally convicted by a Pakistani court in Karachi. He was disliked by many newspapers and journalists for his pro-India and anti-Muslim League views. He was totally against Partition and hated the idea of a religious State.

Do you think young Indians who live in a self-centered society bother about Manto and his stories? Is it relevant to their lives today?

Manto is a superb craftsman in fiction, as good as Guy de Maupassant. Those who like reading fiction (and I am not among them) will enjoy him for this reason.

In his non-fiction, he is an inviting figure because he immediately attracts to those who are liberal towards him. This is why he should be read in any language one can access him in.

How is Manto remembered in Pakistan today? And why did Pakistan not acknowledge his greatness as a writer when he was alive?

On the subcontinent writers are not heroes, unlike in Europe. Manto is a particularly difficult figure because ideologically he was inclined against Pakistan. But there is a large and influential group within Pakistan today, including many young people, who see him as a figure relevant even in our times.

Why was Manto so bad in managing his finances? He always used to borrow money from people and never return it. Could you get any answer to this while researching his life?

Why was Manto so bad in managing his finances? He always used to borrow money from people and never return it. Could you get any answer to this while researching his life?

Writing does not pay well in India, and that was the case even then. He was not well-off and lived in a flat that was given to him as refugee property. Incidentally, that building, Lakshmi Mansion, is also the place Mani Shankar Aiyar was born in 1941.

Manto did not mind borrowing money and I suspect many of his friends did not mind lending or just giving him money because he was so brilliant. But it is true that he mismanaged his money, drank far too much according to stories from those times and his own admissions -- though strangely I can only find references to beer in his writing.

His family would have suffered because of this.

Among the many Urdu writers, why did you choose to translate Saadat Hasan Manto? What appealed to you about him vis a vis other Urdu writers like Krishna Chander, Khwaja Ahmed Abbas, Ismat Chughtai or Qurratulain Hyder?

The big reason was that these essays had never been translated before, which is quite remarkable given their subjects, such as the riots in Bombay, the Hindi-Urdu debate, his trials and so on.

I began doing the translations purely as an exercise at first, but as I went on, I realised that there was something of great value that I had the opportunity to put out.

How did you decide to pick which stories to translate in this book?

I went through the volume Manto Kay Mazameen, meaning Manto's essays, from his collected Urdu works and picked out what I thought was interesting.

This was a mix of some long essays, such as Meri shaadi in which Manto describes his move to Bombay and his work in Bollywood (which was not called by that name then), and another long essay on why and how Indian men molest women.

Then there were short pieces on potholes, on the art of bumming cigarettes, on arms control and so on.

When did you learn Urdu and how difficult was it?

When did you learn Urdu and how difficult was it?

I began learning Urdu around 2000, and took up classes in my free time at Bombay University's Kalina campus, then I took Arabic and Farsi classes in South Bombay. Lastly, when I could afford it, a series of maulvis came to tutor me at home or, in the case of one maulvi in Ahmedabad, in my office.

I did not find it particularly difficult because I was familiar with the spoken language through Bollywood. The script was foreign to me, as a Gujarati, but I was able to start reading after the first year or so.

What kind of practice did you undergo to perfect the language?

At the beginning, I approached it as a child would, which is to say reading primers and writing as often as I could find the time to be familiar with the script.

Later, as my reading improved, I began reading the newspapers from Pakistan every morning, particularly Jang, Roznama Express and Nawa-e-Waqt.

After a few years I was good enough to write a column for a Pakistani English weekly, The Friday Times, in which I translated the Urdu papers.

Which is your favourite Manto story and why?

In the series I have translated, I would say it is Hindi Aur Urdu, a short, sharp and witty piece that should be read out aloud because it is written as a conversation.

In his fiction, my two favourite pieces are Bu (about a young man in Bombay called Randhir who is intoxicated by the scent of a peasant woman's armpit) and Toba Tek Singh.

What is the future of Urdu and Nastaliq scripts in India?

What is the future of Urdu and Nastaliq scripts in India?

Nastaliq is dead. Among Hindus, nobody can read it. Among Muslims and Sikhs, only old people know it in the upper and middle classes. The lower middle class and poor Muslims have access to it because of newspapers and their knowledge of Arabic (Naskh) script, but there is little modern work in it compared to other languages.

Urdu newspapers exist, but their circulations are low and per-copy readerships are high (meaning that one copy is shared by many people, which tells us something about the readers). Even Shabana Azmi cannot read Urdu, which is remarkable.

But this is not necessarily a problem. When I was discussing this issue with Gulzar, he said Devnagari could easily accommodate all the Perso-Arabic sounds by the simple device of using a dot under letters like K and Q and G to indicate the Urdu letters khay, qaaf and ghain.

So far as the future of Urdu is concerned, as long as we have Bollywood, Urdu Zindabad!

Pakistanis think Bollywood is Urdu (and what Vajpayee speaks is Hindi), while we think Bollywood is Hindi (and what PTV speaks is Urdu). But both are right. Same language, different scripts.

Google, Twitter, Facebook don't support the Nastaliq script which is more Persian oriented and are encouraging the Naskh script which is the Arabic script. Do you think if this happens, we will lose the Nastaliq script in the next 50 years?

Google, Twitter, Facebook don't support the Nastaliq script which is more Persian oriented and are encouraging the Naskh script which is the Arabic script. Do you think if this happens, we will lose the Nastaliq script in the next 50 years?

I think so. Naskh has wider appeal because of the Arabic world. I think future generations will be familiar with Urdu writers and literature through either Devnagari or Roman Urdu (meaning Urdu written in the English alphabet).

This latter in particular, I think, is the direction where things will go.

Lastly, do you think the Urdu language was intentionally killed by the supporters of the Hindi language because of communalism politics post partition?

Manto says languages are neither created or destroyed by design. I agree with him.

You can buy Aakar Patel's fascinating book Why I Write here.

© 2025

© 2025