'But he was very quick and did a very stylish adab.'

'Of course, I didn't expect him to hug.'

Do girls need to swallow the sun to shine in India?

They literally did have to, back in the day, to conquer their worlds. Even today, to prove themselves, women must radiate abundant light to overcome much of the darkness that often can be a stumbling block for them to succeed.

Retired diplomat Lakshmi Murdeshwar Puri knows a lot about swallowing the sun. She learned about it at her Aai's knee.

The daughter of a 'fierce feminist' and one of the first women to earn a postgraduate degree in law in Maharashtra, Puri's mother Malati Desai broke ridiculously finicky, rigorous caste and regional barriers -- waiting eight years -- to marry her Chitrapur Saraswat Brahmin poet-lawyer husband Balkrishna Ganesh Murdeshwar from Karwar.

Right from young, her mother instructed her, 'Don't ever be told you are weak or vulnerable because you are a woman. Women are the strongest creatures god made! Be forever strong. You can't defy your nature!' And both her parents, who she describes as iconoclasts, feminists impressed upon her: 'Be someone in your own right'.

Puri went on to make her mom proud, eating the sun off for breakfast, when she trained as an officer for the Indian Foreign Service corps; married a fellow diplomat Hardeep Singh Puri; was posted in various capacities to Japan, Sri Lanka, Hungary, Switzerland, on the Pakistan desk in New Delhi; and then joined the United Nations going to become an assistant secretary general, working with UN Women on gender equality and empowerment of women. How Malati Desai Murdeshwar would have approved.

Today Lakshmi Murdeshwar Puri is an author too. Her first novel Swallowing The Sun, published by Aleph, was released in January.

Sprinkled with poetry and religious verse, it elegantly draws together several strands, warping and wefting an epic tale, as iridescent as a Paithani sari, against the rich backdrop of turbulent, seething but idealistic pre-Independence India, following a determined young woman who tramples rules and hurdles, sweeps imperiously past obstacles to become a brave new heroine of Young India. Her name is Malati.

While the character traits of many of the leading figures in Puri's masterwork reflect that of her parents and the book is a subtle and affectionate ode to Malati and Balkrishna Murdeshwar, it is not a biographical novel.

Standing in front of a literary kind of kadhai, cooking up a rich and tasty plot, Puri decided to toss in a whole slew of piquant ingredients.

Swallowing The Sun wanders from rural Ratnagiri to a royal court in Madhya Pradesh, stops for an interval at an Indore orphans' boarding school, journeys to the dacoit badlands of the Chambal, winds its way to cosmopolitan, brash Bombay, takes a detour to the banks of the Ganga in Varanasi, before heading later to snobby British-era Shimla and finally to post-Independence Delhi.

You can almost experience the joy Puri had throwing colour and spice about, as feisty Malati is ambitiously pushed to different locales to take on new sets of challenges and the novel's trajectory takes an unexpected twist or turn.

Discussions on caste, religion, romance, women's education, law, food, death, hunting, insanity, nine-yard saris, theatre, poetry, literature, horsemanship, nathya sangeet, Gandhism, Veer Savarkar, the British, all adventurously find their way into Swallowing The Sun.

Explains Puri to Vaihayasi Pande Daniel/Rediff.com: "I keep saying this: It is not a biography nor an autobiography because, of course, it's of a different generation. But it is very much inspired by my parents.

"Much of their soul and spirit is captured in the characters of Guru and Malati. The trajectories are not identical... certainly not, but there are some milestones that may be similar."

One of Puri's purposes in setting it in the time of her parents was to present and bring alive the idealism and distinctive mood of that era and show "the values that they represented, that generation.

"I was born to them when they were 45 years old. And as a post-Independence child for me, it was a very fascinating era and epoch that they represented and they kept talking about or recalling and invoking.

"That also roused my curiosity about the world that they had inhabited and mentally, emotionally and intellectually continued to inhabit... So this is the context in which you have to look at their association with this book or they're inspiring this book."

Apart from Puri's parents' wistful and deep emotional connection with a pre-1947 India, a time of so much "socio-political upheaval and cultural rebirth," they also brought up their three daughters, Kusum, Indira and Lakshmi, in a highly progressive and artistic atmosphere, while stressing the need for the girls to have their own career, education.

"The cultural, educational and literary environment that they created was also very much responsible for the careers we pursued. And this literary offering.

"Even when I was wanting to tell a story, inspired partly by their life, the medium had to be a literary novel.

"We grew up in a very literature-loving household. My parents were vidwans in Sanskrit... My mother made me study Hindi literature with a pandit."

But many genres of literature swirled about Puri through her childhood and teenage years and is reflected in the novel, be it T S Eliot, Tennyson, Dickens, Greek mythology, Indian epics, Shakespeare, Sanskrit scriptures, Premchand, the Gita, Marathi poetry, Chhayavadi poets.

The sundry obsessive conversations about food in her novel can be traced back to her parents too, her mom in particular, who she says was a talented cook, talked food eloquently and passed on her cooking skills to Puri.

"Like her I consider Indian cuisine to be the greatest, most sophisticated and pleasure-giving. One of the main rasas of living!"

Locating her novel in multiple places required a bit of serious research, although she had a lot of memories, recollections, letters, and "stories" of her parents and their contemporaries to go on and she was able "to recreate, burnished by my imagination, these places from the eyes, the ears and the senses of my parents."

She is intimately familiar with Murdeshwar, Ratnagiri, and those rustic environs, right from her childhood, but Varanasi was a study project.

Guna and Shivpuri she had knowledge of too, having, as she puts it "imbibed that atmosphere of a princely state."

Puri is now rather keen to go back to those milieus "to see how did I recreate these places and how have they changed. And just the magic of that imagination that may have shown these places to be different from what they were or are."

Her novel is set around 100 years ago. Has India travelled all that far in a century?

She chooses to create dialogues on many topics between various pairs of characters in her novel that make you question that.

The barriers that Malati, her sister Kamala and other women characters bested in Swallowing The Sun, which her broadminded father Baba also battled when he tried to get all the village girls educated, not just his daughters, or that Gandhiji referred to when Malati met him, were not speed breakers confined only to Malati's time.

The patriarchy that existed then is not even close to extinct today.

Puri feels that, in spite of momentous attitudinal shifts, and being on the right path, the roadblocks yet exist in some form or another, even for girls of privileged backgrounds, over 75 years after freedom was won for our nation.

"The mindset change that Baba tries to bring about is a continuous process, whether it was then, whether it is today, when we have the Beti Bachao Beti Padhao campaign.

"That is exactly what he was trying to do then too, to prevent child marriage, child motherhood and put an emphasis on education.

"Removing discrimination in the workforce, whether women should work or not or is their place in the home -- there is that attitude.

"Then there is this question of girl aversion and boy preference -- that attitude. And the issue of access to resources, economic and financial, property rights, autonomy of women...

"All of these issues were very much there at that time and are there today."

These problems, Puri underlines are faced as much in urban areas, among the more educated and better off too, and in the middle classes -- "there is still the need to fight attitudes" and to make sure "women themselves to claim their rights."

Further, Puri believes that lack of discrimination against women should also be mirrored today in the higher echelons of policy making and governance and lawmaking.

"The whole issue of their voice, participation and leadership in governance (exists). It was there then and it's a continuing battle today."

Perhaps absence from a homeland births a longing to bring it closer and so Swallowing The Sun got its first contours when the diplomat began writing the 424-page novel 22 years ago on an ambassadorial assignment to Budapest.

It was planned as a trilogy, but Puri is not sure if that shall come to pass. She got back to constructing the book a little while after she returned to Delhi post-retirement in 2018.

Her career kept her rather busy in between. Each of her postings had highpoints and challenges that she enjoyed taking on.

Many related to being a woman in the foreign service.

In Tokyo, where she and her husband were first posted, in the mid-1970s, as second secretaries, after mastering the language, Puri was not put in charge of liaising with the press for the information and media division of the embassy.

It was felt that it would be difficult for a woman diplomat to interface with Japan's deeply gender-biased society.

Puri objected and requested then ambassador to Japan, Eric Gonsalves to give her a chance.

Utilising the power and grace of six yards of fabric and her command of Japanese, "I met all the editors of the biggest newspapers in Japan.

"Far from being blocked out, I actually got entry, possibly because I was a Japanese-knowing Indian woman in a sari. There was that novelty.

"Plus, once we connected, they started respecting me.

"It was one of those lessons early on in my career: When you come across speed breakers, go over them at a high speed. Then I never looked back."

The highlight of working, next-on the Pakistan desk as an undersecretary in New Delhi was a visit to Pakistan. When Puri was assigned the desk there had been a dramatic, unexpected change of guard in Pakistan. "(Zulfikar Ali) Bhutto had just been executed when I joined.

That was 1978. General Zia (Muhammad Zia-ul Haq) had taken over and he was bringing Pakistan, more and more, into a very Islamist kind of framework, which was also very misogynist."

Both governments were bravely hoping for a thaw. Puri, known to be a hawk, and one in a series of strong women who had been assigned to this post that she terms a "launch pad" and a "lesson for life," was engaged in an exciting range of work, like confidence-building measures, security issues, territorial concerns.

"It was a very complex, rich, sensitive portfolio, and it involved almost every part of the Government of India, particularly the home ministry" and then prime minister Indira Gandhi, ministers and chiefs of the armed forces sat in on the meetings.

As a liaison officer she was part of the first ever Sikh Jatha, or group, visiting parts of Pakistan and Islamabad and meeting the general. But her name was missing from the delegation list that was that day heading to Zia's house.

"Natwar Singh, who was then the ambassador, said, 'Why is her name missing? She is the liaison officer. She has to be there'.

He called the military advisor to the president and said, 'How come her name isn't there?' He said, 'No, women we don't really allow...'

"Natwar Singh wouldn't take no for an answer. He told me to get into his car and we landed up at General Zia's residence and they couldn't prevent him from taking me inside.

"I was standing there in the line and he, of course, hugged every Jathedar. When he came to me, he was taken aback.

"He looked at me with his lidless eyes, real startled. But he was very quick and did a very stylish adab.

"Of course, I didn't expect him to hug," she says with a hearty laugh.

After 15 minutes, while she was taking notes of the interactions, a waiter came over with a message from the "Begum Sahiba" and asked her to join Zia's wife, who was sitting nearby.

Puri was in a quandary, but decided it might be construed ill-mannered to refuse an invitation and went across to Begum Shafiq.

"She was waiting for me with tea and everything laid out on the other side of the lawn. I didn't know what to do. If you say no, it would be rude.

"So, I joined her there and left the men to the official discussions. It was, of course, a very interesting discussion with her because she and General Zia were from Chandni Chowk and from Delhi, and their families had migrated to Pakistan during Partition from there.

"She asked me about Chandni Chowk and what are the fashions for the salwar kameezs? What is the size of the pocha (outward flow of the salwar)? And many other things, including, 'Do they still do bottom pinching in the crowded Gandhi Chowk gullies'?! It was as interesting as that."

Pakistan under Zia, Puri, a skilled and warm raconteur, colourfully describes, was very "mulish" about not allowing women, even ministers in official discussions and banquets, so much so that her later boss J N Dixit was led to comment that if Indira Gandhi were to visit would she have to 'sit in the pantry?!'

The Pakistan division experience, she recalls was "invaluable" and provided key tutorials in bilateral diplomacy -- "one felt one was learning, but one felt one was contributing very substantially to the relationship and managing the relationship."

Her subsequent Sri Lanka posting was at the height of the ethnic crisis, during the heady, history-making days when the India-Sri Lanka Peace Agreement was being negotiated.

"It was soon after Mrs Gandhi's assassination. Rajiv Gandhi had taken over. He reviewed the whole Sri Lanka policy, and wanted to cut India's losses and be the broker of peace in Sri Lanka between the two communities."

It resulted in India having to send peacekeeping forces to fight the LTTE and Puri had a ringside seat of the goings on.

Colombo was again "an unmatched, unprecedented diplomatic experience" doing what diplomacy is meant for, which is "making peace, resolving difficult issues that are of national interests" as "real actors in that effort."

All the stuff of a "thriller" that she would like to one day write about too.

Puri's term in Hungary was the start of her growing her skills in multilateral diplomacy. She was concurrently accredited to Bosnia-Herzegovina, where UN peacekeeping forces and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe were trying to bring peace to this area that, Puri says, was like a horrific live "open air war museum," treacherously planted with extensive landmines.

India had provided the largest contingent to the greater International Police Task Force operating there and were valued for their professionalism, discipline and experience in handling sensitive communities.

From the multilateral role of dealing with the UN (and similar such organisations), Puri eventually moved to becoming part of the organisation, where she spent 15 fruitful years, first in international trade and commodities division of UNCTAD, later in the Least Developed Countries.

She ended her career with a seven-year stint in an area very dear to her heart when she was appointed in 2011 deputy executive director, at assistant secretary general level, of the newly-founded UN Women, an organisation she worked hard to give roots and build.

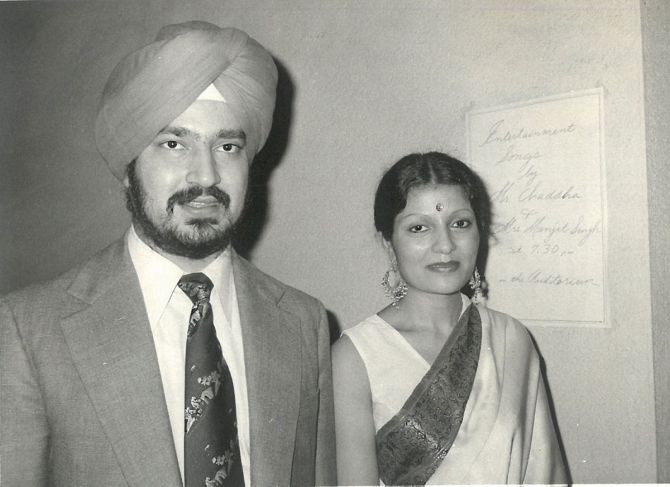

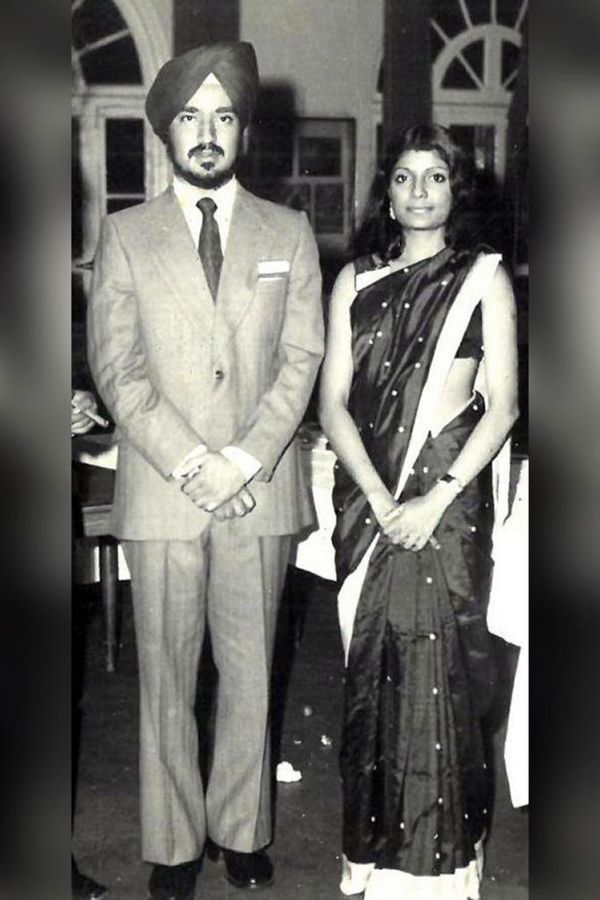

Puri met her husband, at the beginning of her career, while they were studying at the Lal Bahadur Shastri National Academy in Mussoorie, where IFS officers train. In three months, they decided to wed.

He was the son of refugees from Peshawar and Rawalpindi, who had lived in a refugee camp post-Partition, but like her had grown up in Delhi, and had been educated in a few of the same institutions.

They had Delhi in common, though she was a Maharashtrian Saraswat mix and he a Sikh.

"The differences were there, religious and linguistic, provincial. But we were Dilliwallahs. That really bridged all the differences and, of course, education.

"I had already become a true Indian -- very eclectic in terms of linguistic affiliations, poetry, music, films. We were very cosmopolitan, both of us, in so many ways."

Getting over the chasms that could potentially divide them and persuading parents to agree was a small difficulty compared to richness of their multicultural married life.

"I'm as much a devout Sikh as a Hindu. I'm spiritually stirred by shabad as much as by my Sanskrit mantras and shlokas that I recite every day. I do both the prayers.

"I enjoy Punjabi literature, songs, language. It's a beautiful and robust language, very evocative.

"You're absolutely right that intercultural marriages, even within the context of India, are very exciting. There may be some initial conflicts -- I won't deny that, the Two State (laughs) kind of situations -- but they are very enriching... Your horizon widens."

The earliest person to read the initial draft of her book was Hardeep Puri.

"My husband has been very supportive of my literary journey. He was the first to read the 270,000-word first draft which I finished one year during the COVID era. And I wrote it on my iPhone and took a print out. He read the whole book in a very concentrated way, gave his feedback. He loved it.

"He was very encouraging. He saw so much of my own ideas, my soul poured into it, my experience distilled into it, my feelings, my emotions. Also, my worldview, of course, that evolves from both family and your own lived experience, isn't it?

"He saw all of that and remarked, 'There's so much of you in the novel?' Of course, there are similarities in the stories of Malati and Guru and Hardeep and Lakshmi Puri's love story."

Puri is acutely aware that for many young Indians -- as India's Constitution turns 74 -- heroic, flag-waving sagas of winning freedom and gallantly fighting for Independence have no connect and they take much for granted. Also, the emotional values of the 1930s and 1940s are not reflected in today's India.

"This is exactly why I want us not to forget. I want the young people today to remember what their forefathers and mothers did -- and I emphasise the mothers also -- to gain freedom and how valuable it is, how it is to be cherished, how it is to be nurtured.

Puri's parents, who were the young of that era, envisioned, wished and worked towards a certain India to be Their Independent India.

She reckons (not in a political manner she clarifies) this generation, who are also the young of this century, need to take lessons from the freedom generation and similarly toil at reimagining the India they want to strive towards by 2047.

"On one hand, we are setting ourselves the target of India at 100 becoming a developed country. We say we are in the Amrit Kaal (golden era) and as we move towards that -- we are also the richest country in youth -- it is they who are really going to be driving what I would call the movement for reaching the Viksit Bharat (Developed India) goal."

Puri has another reason why we must tap history, and the flavour of pre-1947 India, to show a way forward into the future: "The period, that I have tried to capture in the novel, was one of great civilisational reawakening; a cultural, literary, musical efflorescence.

"It was a renaissance happening, particularly in Maharashtra. It is that sensibility, that awakening, that is also, in a way, happening now in India... It is very important to evoke -- what I think we are very much doing in some ways -- this civilisational awakening."

Puri's Swallowing The Sun is not a simple recital of tales about a long-gone tumultuous time. It's storytelling with a purpose -- the blueprint for the future lies also in a rich past.

Feature Presentation: Ashish Narsale/Rediff.com

© 2025

© 2025